The problem with this trend has nothing to do with glorifying organized crime.

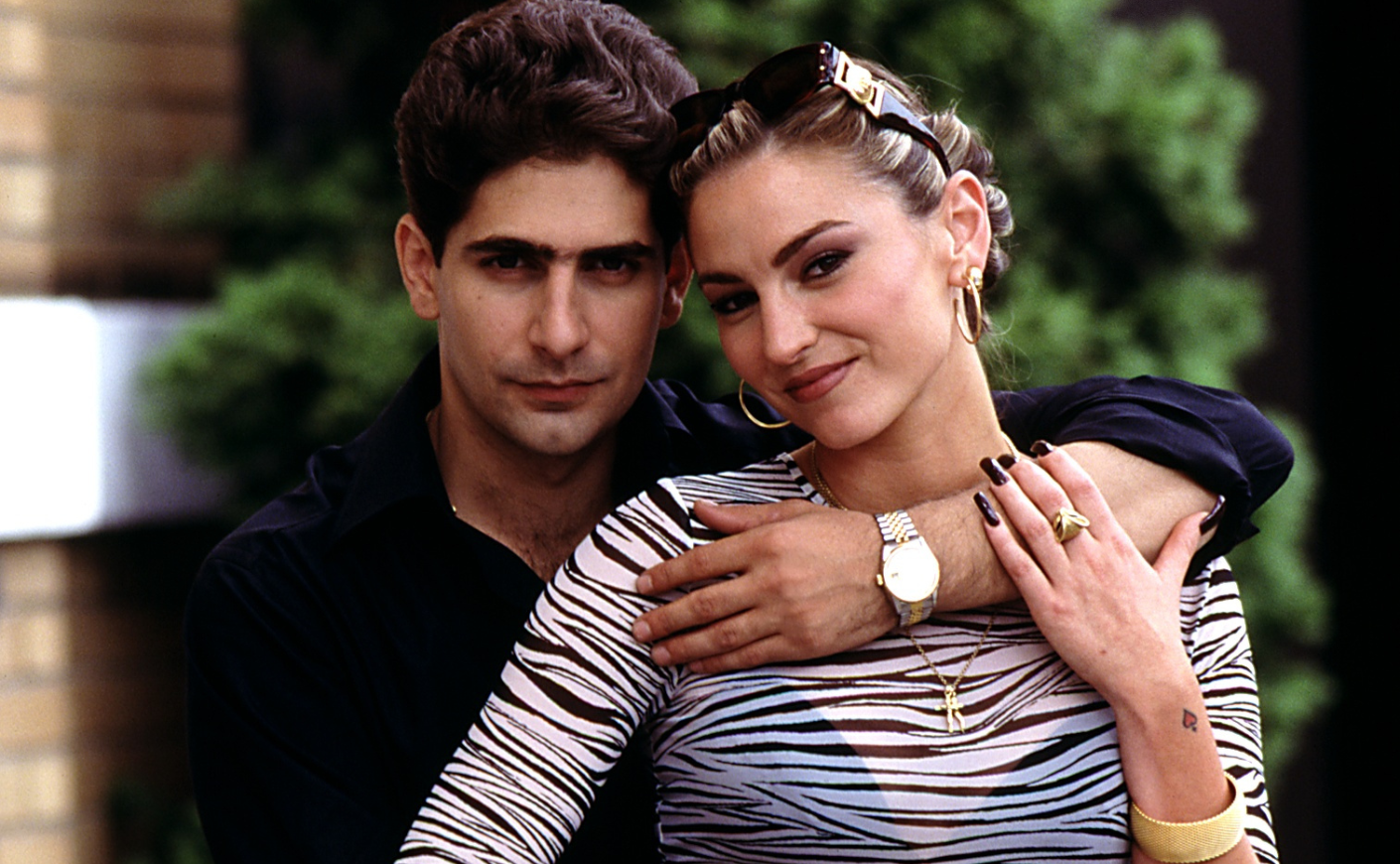

If you’ve been on TikTok or read a single online fashion article in the last few weeks, you’ve probably come across the so-called “mob wife aesthetic.” The hallmarks of this trend are exactly what you’d imagine from the name: big, furry coats; leopard print garments; and lots of leather (pants, mostly). Complete the look with a bold red lip, chunky jewelry, oversized sunglasses, and a voluminous hairdo —gabagool and husband in the mafia optional. If you’ve ever seen The Sopranos or watched Goodfellas, you can probably conjure up the image pretty easily.

Since its inception just a few weeks ago, the mob wife aesthetic has taken on a life of its own: Videos with the hashtag #Mobwifeaesthetic have been viewed over 175 million times on TikTok. Francis Ford Coppola weighed in on its popularity on Instagram, and there’s even a (probably satirical) Jewish offshoot of the fad. But the trend hasn’t come without controversy. Below, we’re unpacking some of the drama surrounding the fad.

Convenient timing?

Within the past year, we’ve seen all sorts of style microtrends explode from TikTok into the mainstream. Anyone remember Tomato Girl Summer? Or the Coastal Grandma Chic that came before it? Most recently, the “Clean Girl” aesthetic was taking over our feeds (characterized by very little makeup, neatly combed hair, and classy jewelry). It seems like every few months, the social media algorithm gods that be — or, in other words, trendsetters — come up with a cutely named way of dressing that then takes on a life of its own.

The thing is, a lot of these TikTok trends can feel manufactured. The trends themselves aren’t exactly novel, they’re just given a catchy new moniker. “Tomato Girl Summer” mostly boiled down to wearing linen, silk hair scarves, and straw accessories — popular garments to wear during the summer anyway. “Coastal Grandma” more or less amounts to women wearing cardigans and floppy hats beachside. Or take blueberry milk nails, which were, apparently, “summer’s most-wanted manicure.” Vogue reported that Sophia Richie and Dua Lipa had been sported wearing the shade. The shade is…drumroll, please…light blue. Not exactly groundbreaking.

When it comes to the mob wife aesthetic, there’s similarly nothing all that new or shocking involved. Wearing fluffy coats during the winter is fairly expected (not to mention useful), and leopard print has been back in a big way since at least 2018 when it was being hailed as a neutral. (And if you want to get technical, it’s been “in” in some form periodically since the 50s, and even earlier.) But dubbing the full package the “mob wife” look seems to have started on January 6, when a 28-year-old woman took to TikTok to declare, “Clean girl is out; mob wife era is in, OK?” The video got over 200,000 likes.

But it wouldn’t be the internet if people didn’t try to derive a deeper meaning. Some social media users think the rise of the mob wife look is a carefully plotted marketing tactic. The Sopranos premiered 25 years ago from January 10, and HBO has been celebrating the anniversary by releasing 25-second clips from the series on TikTok. With the convenient timing of #mobwifeaesthetic, some think that the trend was planted by HBO to drum up publicity and encourage people to watch The Sopranos. For what it’s worth, a spokesman for HBO told the New York Times that the trend is “a testament to The Sopranos and its enduring impact on culture” but didn’t admit to having a hand in starting it. And the woman who appears to have started the trend told Harpers Bazaar that she had “no idea” about the show’s 25th anniversary and was just reporting what she saw on the streets in Manhattan.

A symptom of a deeper problem

Some critics are pointing out an even bigger problem with the mob wife aesthetic — and it has nothing to do with potentially glamorizing organized crime. In fact, it has more to do with the sudden emergence of the trend and others like it — and the implicit encouragement to buy things in order to embody them.

TikTok trends aren’t emerging on the runways twice a year; they’re appearing out of the algorithm every few months. Lakyn Carlton, personal stylist and sustainability educator, notes that, “Trends, historically, form in opposition or response to something, especially trends among youth.” In the 90s, the grunge look’s emphasis on secondhand clothing exemplified a rejection of consumerism; flappers embraced a more androgynous look as a way of renouncing societal expectations. “But what is ‘clean girl’ a response to? What is the mob wife aesthetic a response to?” Carlton asks. “They pretty much exist only to respond to other trends and garner attention.” She adds that it only takes a few influencers to declare a look the Next Big Thing. “It’s very easy to push a couple videos to millions of viewers and make it seem like there’s this big new thing to jump on,” she says, “even if it was initially just a couple people talking about it.”

Trend and cultural strategist Anu Lingala says cultural moments like the mob wife aesthetic aren’t really trends, per se — “they’re visual or styling aesthetics that people are playing with, but they’re not necessarily connected to bigger cultural movements and shifts and the things that actually influence a trend with longer term significance.” She adds that “mob wife” likely won’t make an impact in mainstream fashion or retail, which is working six months ahead and already putting out designs for spring.

But even though we’ll probably all forget about mob wives by the time next winter’s coats are unveiled, the rise of fast fashion allows the masses to participate in a trend right now. When you see a new look on TikTok, you can immediately go onto Shein or H&M — or any of the multitude of retailers out there peddling cheap, and cheaply constructed, clothing — and spend a relatively small amount of money on a garment you’ll probably forget about by the time the next aesthetic rolls around. And that’s a huge problem amidst the climate crisis — it’s pretty much the antithesis of sustainability.

The United Nations Environmental Program estimates that the average consumer today buys 60 percent more clothing and keeps it half as long than they used to, compared to consumers of only 15 years ago. A Business Insider analysis found that fashion production accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions — and 85% of all textiles go to the dump every year. Part of that waste is due to companies overproducing, but part of that is also on consumers: Demand for cheap clothing caused global production to double between 2000 and 2015.

Lingala says that on its own, experimenting with your personal style can be a good thing, especially if you find a signature look that sticks. “You might always dress ‘Quiet Luxury,’ and I might always dress ‘Coastal Grandma,’” she offers. But, Carlton cautions, you can’t build sustainable style and get the most use out of everything you own “if you’re constantly trying to acquire the newest, hottest thing.”

Carlton says there’s one unexpected silver lining of the mob wife aesthetic: People are encouraging others to go vintage with their fur instead of creating a demand for new pieces. But ultimately, she says, “The most sustainable clothing is what you already own.” In other words, instead of asking yourself, Where should I shop more sustainably? the question should be, Should I be shopping at all?