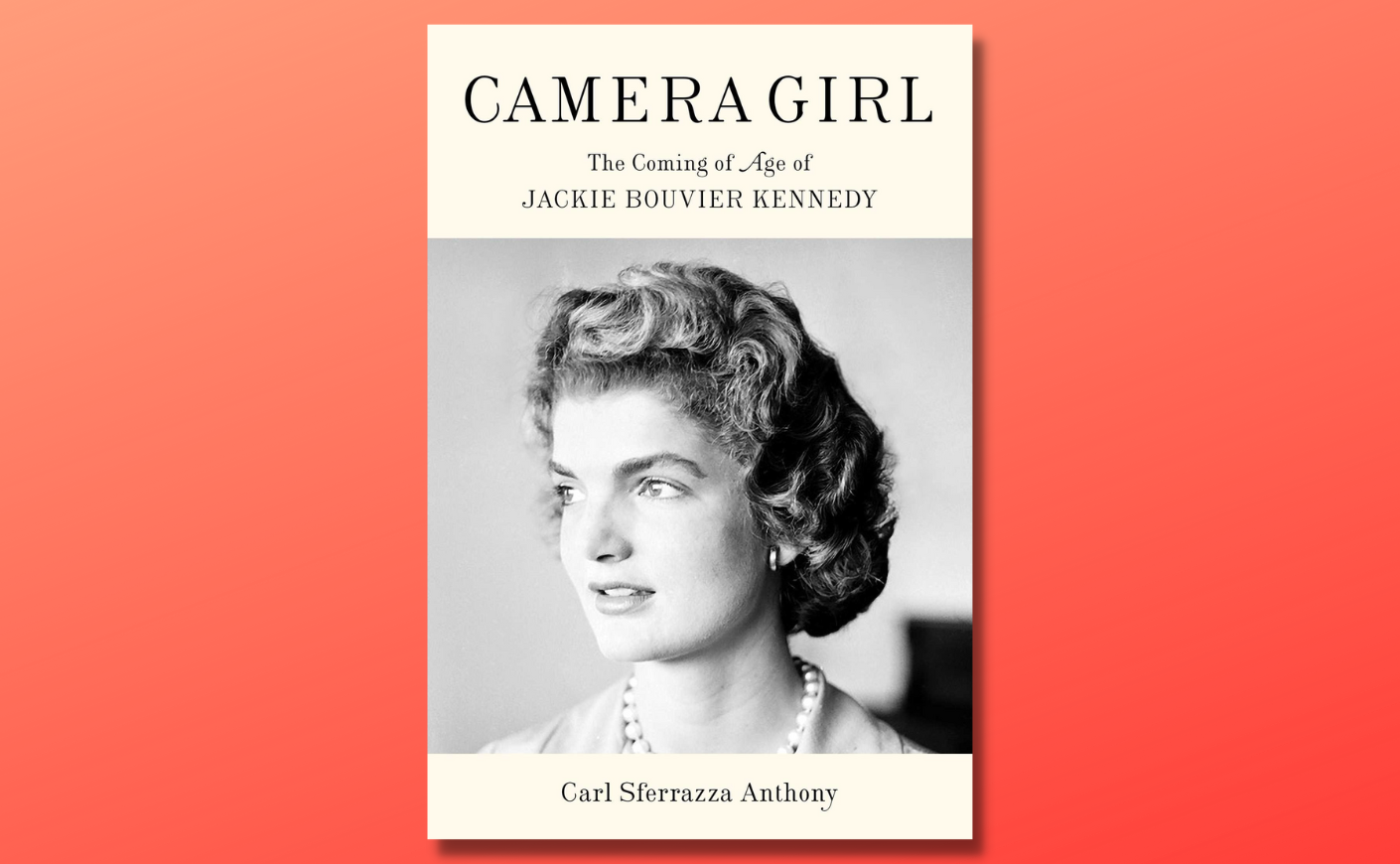

An excerpt from Camera Girl: The Coming of Age of Jackie Bouvier Kennedy.

Jackie Kennedy is arguably the most famous first lady in American history, and after decades of dissecting everything from her unforgettable fashion to how she influenced our country’s culture, you might think there’s nothing new to learn about this formidable figure. A new book is here to prove that wrong — and uncover a treasure trove of juicy stories in the process.

In Camera Girl: The Coming of Age of Jackie Bouvier Kennedy, author Carl Sferrazza Anthony investigates the early years of the woman who eventually ascended to the White House. The book explores her college years, her formative adventures in Paris, and a notable job you may not have realized she had. The title comes from Jackie’s role in the early 1950s as the “Inquiring Camera Girl” for the Washington Times-Herald. As part of that work, she’d hit the streets to photograph everyday people and ask for their opinion on topical questions that often revealed as much about the woman asking them as the ones who answered.

And while the book is specifically about her pre-White House years, it does chronicle how she got there. In the exclusive excerpt below, the author explores the early courtship of America’s most glamorous couple, including why it took JFK so long to pick a mate, how Jackie ingratiated herself into his influential family, and what the future president’s notoriously voracious sexual appetite meant for their budding relationship.

Unexpected news about Jackie’s sister was announced in national newspapers on Dec. 12, 1952. After just nine weeks of work, Lee quit her job and became engaged to Michael Canfield, whose father was the president of the book publisher Harper & Row. The era’s societal judgment that her younger sister “beat her to the altar” may have prompted a pang of inferiority only reinforced by the continued deafening silence from Jack Kennedy.

Twelve days after he was elected to the Senate, Jack was a groomsman in the Williamstown, Mass., wedding of his friend Robert Kramer. Ten days later, in the last week of November, he left for a European trip with Torbert MacDonald, a personal friend and political ally since they’d been Harvard roommates. Torb was not only Jack’s regular companion on overseas trips that had them both womanizing with abandon but a politically ambitious and savvy adviser as well. (He would seek and win a U.S. congressional seat in 1954.) They went to England, Ireland, Italy, and France, where, in Paris, Jack met with foreign affairs officials to discuss the situation in Vietnam. After three weeks away, Kennedy returned on Dec. 17 and stayed in Boston to preside over a children’s Christmas party at the VFW named for his late brother. His next trip to Washington was to interview candidates for his new Senate staff, not to take Jackie to any holiday parties. The Bouvier stole and gown were seen more on the mannequin than on their creator.

Jackie’s stepbrother Yusha had recently updated her that her former beau, writer John Marquand, had a book that was doing well. “Very pleased to hear his book is to be a Book of the Month,” he informed her.

Months earlier, in a letter to Father Leonard that she wrote after her July visit to Hyannis, she had quoted Byron as saying that love is “woman’s whole existence,” but that men kept it separate from their larger public lives. Her intuition that Kennedy viewed marriage as a political tool was correct. Dave Powers flatly admitted that Jack “wondered about it, whether or not he would have to marry a Massachusetts girl, you know, another Irish girl, this sort of thing. And he waited until he was elected senator to find out whether there was any loss of votes there.” Jackie Bouvier did not yet grasp the extent to which not just Jack but Bobby and their father would ruthlessly evaluate her as a political commodity. She told Gore Vidal that she once overheard them, recalling that “they spoke of me as if I weren’t a person, just a thing, just a sort of asset, like Rhode Island.”

In the weeks after winning the Senate election, Jack mentioned to several close friends that his father was urging him to consider the pursuit of the presidency. Observed Charlie Bartlett, “I think Jack knew the race for the Senate was the beginning of a long race for the presidency. I think Joe had the whole thing sort of in his mind and Jack was ready to go.” Jackie, however, was never one of those who believed Jack became determined to seek the presidency only after winning the Senate and in obeisance to his father. “I think he was probably thinking about it for an awfully long time, long before I even knew,” she reflected. “It was always there.”

By year’s end, it had been nearly three months since she’d seen or heard from Jack Kennedy. She had no sense of whether he had, perhaps, begun dating someone, found some reason to consider her unsuitable for him, or there was some unspoken issue behind his unwillingness to move forward with their relationship.

Initially, she presumed that, like many men, he would have to be coaxed into marriage, and her anxiety found its way into her column: “How do you expect to get married?” “How did you propose or how were you proposed to?” “What is your candid opinion of marriage?” “Can you give me any reason why a contented bachelor should get married?” “What is the food of romance?” “The Irish author, Sean O’Faolain, claims that the Irish are deficient in the art of love. Do you agree?”

In early 1952, she had asked, “Should girls take advantage of Leap Year?” Now at year’s end, she returned to the subject, asking, “What advice would you give a girl who wants to marry before Leap Year is out?” Jackie seemed to take aspects of the advice of barber Tom Lascola — “Stop waiting for him to propose to you. Propose to him” — and bookkeeper Jean Pievyak, who advised, “He’ll get scared . . . sit tight and wait until next year.”

While Jackie wouldn’t propose, neither would she wait.

Ambassador Joe Kennedy was already in residence at the family’s Palm Beach home by the time the senator-elect arrived on Dec. 21, joined by all the family by Christmas Day. Before Jack arrived, however, Jackie came to see his father.

Some thirty years later, the historian and former Newsweek editor Ralph G. Martin left a brief record of an overlooked incident that seems consequential at this critical point in Jacqueline Bouvier’s trajectory. It involved the “mutual affection” that was “quick and lasting” between her and the ambassador, as Martin termed it: “She was vacationing with the Auchinclosses at Hobe Sound, and dropped in on the Kennedy home in Palm Beach. Only the father was there. The two seemed determined to charm each other, and they did. They went swimming, made each other laugh, talked about everything from Cardinal Spellman to Gloria Swanson. When she left, she had an ally and an admirer.”

As Jackie would later observe, “I’m more like Mr. Kennedy senior than any other members of his family.” The family’s friend Robin Douglas-Home, the British pianist and author, asserted that “the only one who really knew her worth from the beginning was Joe Kennedy.”

Jack Kennedy’s friend and colleague Florida senator George Smathers would later claim that Jack “told me that his father told him it was time to get married, and his father preferred Jackie.” His more intimate confidant Lem Billings disputed this: “Nobody would have talked to Jack at 35 that way, including his father,” especially since Jack “had thousands of girls” from whom he could make his own marital choice. If the ambassador was making arrangements to advance Jack’s best interests, however, “Mr. Kennedy didn’t ever let Jack know it,” Billings added.

Within days after Jackie’s meeting with the ambassador alone, there appeared two items in nationally syndicated gossip columns. In her column “The Gold Coast,” appearing in the Dec. 21 Miami Daily News, Aileen Mehle reported, “Senator-Elect Jack Kennedy, who is one of the matrimonial catches of the decade, what with being young, intelligent, good looking, and rich (but not well groomed) is pretty excited about Mrs. Hugh Auchincloss’s daughter Jackie Bouvier, who is young, intelligent, good looking, rich, and very well groomed.” Two days later, on Dec. 23, Dorothy Kilgallen, who wrote the “Voice of Broadway” column, predicted that “U.S. Senator-elect Jack Kennedy and lovely socialite Jacqueline Bouvier will waltz down the aisle early in 1953.”

It was the first time Jackie and Jack were linked together in the press. Had the Ambassador been the source for the tips? If so, it was not the first time that Joe Kennedy had used his wide network of personal contacts in the press to plant a story about his son’s private life, without his knowledge, to serve what he believed to be the best interests of Jack’s career.

On Jan. 3, shortly after the gossip items linking them were published, Jack invited Jackie out. The previous winter, on their first “date” at the Blue Room, he had requested that Dave Powers join them. This time, Jack asked along Lucy Torres, Jean Mannix, Lois Strode, Mary Gallagher, and Evelyn Lincoln, women on his new Senate staff. The “date” was the Eighty-Third Congress’s opening session, when he would be sworn in as a U.S. senator. They, along with his new colleagues and family members, watched as he was escorted onto the Senate floor — certainly more exclusive company than the thousands of women at the campaign tea party when Jackie had last seen him, but it was still a public event, hardly an opportunity for them to reconnect in a personal way.

Further underscoring the point: Three days later, Jack attended an annual New York charity ball with the striking Maria Carmela Attolico, daughter of the former ambassador to Germany. At the same time, he was also pursuing Betsy Finkenstadt, sister of one of Bobby Kennedy’s groomsmen, though Lem Billings thought it was simply because “he never was successful in interesting her.” Asked by a reporter if he was “swamped” with marital offers from women, Kennedy jibed, “You would think so, but nothing seems to happen.”

Just as with his carefully plotted long game to win the Senate seat, however, Jack Kennedy was methodically laying out his plans for the next momentous chapter of his life. And just like Jackie, when the issue was serious, he kept his own counsel.

Thus it came as a complete surprise to her when, at some point in the first two weeks of 1953, Senator Kennedy asked Miss Bouvier to be his date to the presidential inaugural ball.

But as the relationship developed, Jackie was divesting herself of a traditional concept of marriage. A monogamous husband could not be expected in the partnership she was pursuing, but the relationship would grant her the opportunity to employ her talents and maintain independence while also giving her the status and stability of a financially flourishing husband and household. That was the scenario Jack Kennedy seemed to offer Jackie with the approach of spring in 1953.

Over time, she would come to see the degree of his compulsive promiscuity to be as much of a chronic condition as his painful back, which occasionally required him to depend on crutches. It would nevertheless prove to be a formidable “challenge,” as she seemingly lightly characterized it, to accept his sexual intimacy with other women as an analogous crutch.

In the decidedly conservative early 1950s, dating and marriage were highly idealized. Yet the famous Kinsey reports, done in 1948 and 1953, concluded that about 50 percent of all husbands committed adultery; other studies suggest it was about 33 percent who did so at least once, although these studies did not make a distinction between sexual and emotional monogamy. Based on extensive research, anthropologist Helen Fisher concluded that “we have two brain systems: one of them is linked to attachment and romantic love, and then there is the other brain system, which is purely sex drive.” Jack Kennedy was the embodiment of this theory.

Once again, Jackie used her column as a mode of research, with question after question about romance, marriage, and infidelity. What she did not — and could not — know in February 1953 was how differently Jack Kennedy was treating her from other women he’d been involved with. His history with women had patterns — but his relationship with Jackie didn’t fit any of them.

As Lem explained, although Jack was “crazy about girls,” he “never really settled down with one girl.” A big part of the reason, his confidant pointed out, was that Jack had “an immature relationship with girls — that is while he was terribly interested in going out and having fun with them at night, I don’t think that he was really terribly excited about having girls as friends.” Bill Walton concurred: “He was very attentive, flirtatious; but if a woman bored him, he would drop her quicker than any known man.”

Other than suggesting he couldn’t help himself and that it was a habit indulged sometimes daily, Kennedy never speculated on what he thought were the psychological reasons for his sexual compulsion. As Chuck Spalding said, “He wasn’t by nature given to that kind of prolonged introspection.” Jack may have avoided thinking about the root cause because he never felt there was anything wrong with being compulsively sexual. The most frequent explanation given was the example and encouragement of his father. It was not merely that the ambassador took unapologetic pleasure with whomever he wished, but he had also encouraged his sons to do so at an early age.

Jack’s awareness of how suddenly death could come may have been another factor leading him to seek pleasure in life while he could. By the time he met Jackie, he had lost his siblings Joe Jr. and Kathleen in plane crashes, and he himself had come close to death three times. The first was when he was only three years old, delirious with scarlet fever. The Latin incantations of the Last Rites of the Catholic Church were shouted above the little boy in bed. He received the Last Rites on two other occasions (in 1947, while crossing the Atlantic, and in 1951, in Tokyo), due to complications from Addison’s disease. Perhaps the most acute observation on the matter came from Spalding, who saw that Jack lived with a “heightened perception about the brevity of life.” Although Jackie had no such brushes with death, she shared his habit of “surveying the scene with a kind of detachment.”

The motives and desires that brought Jack and Jackie together are typically said to have been sex on his part and money on hers. Often neglected, however, has been the full consideration of their mutual ambition.They shared a vision of a free and democratic world and wanted the sort of power that would allow them to encourage its realization.

As the spring of 1953 approached, Jack entrusted a special project to Jackie that served to prove to her that he was the sort of partner she’d longed for but had come to believe was impossible to find. It would demonstrate that he wanted to join forces with her, not merely appreciating her intellectual ability as a sort of trophy but wanting her to put it to use. It would make him irresistible to her, and propel what became, arguably, the most momentous decision of her life.

Feb. 10 and 20 were the first times that Miss Bouvier’s name was written into the official record of the senator’s business schedule, and it may have been on one of these significant dates when they first discussed what the project would entail.

Kennedy intended to become a national leader on the issue of the growing controversy over aid the United States was providing to support France in defending its colonial control of Indochina, most specifically in Vietnam, against the increasing success of Communist guerilla fighters based in northern Vietnam, backed by China. He needed to first become an expert on the issue and fully understand the complex history of France’s presence there and its justification for delay in granting Vietnam full independence. He needed the help of Jackie Bouvier.

Excerpted from Camera Girl by Carl Sferrazza Anthony. Copyright © 2023 by Carl Sferrazza Anthony. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.