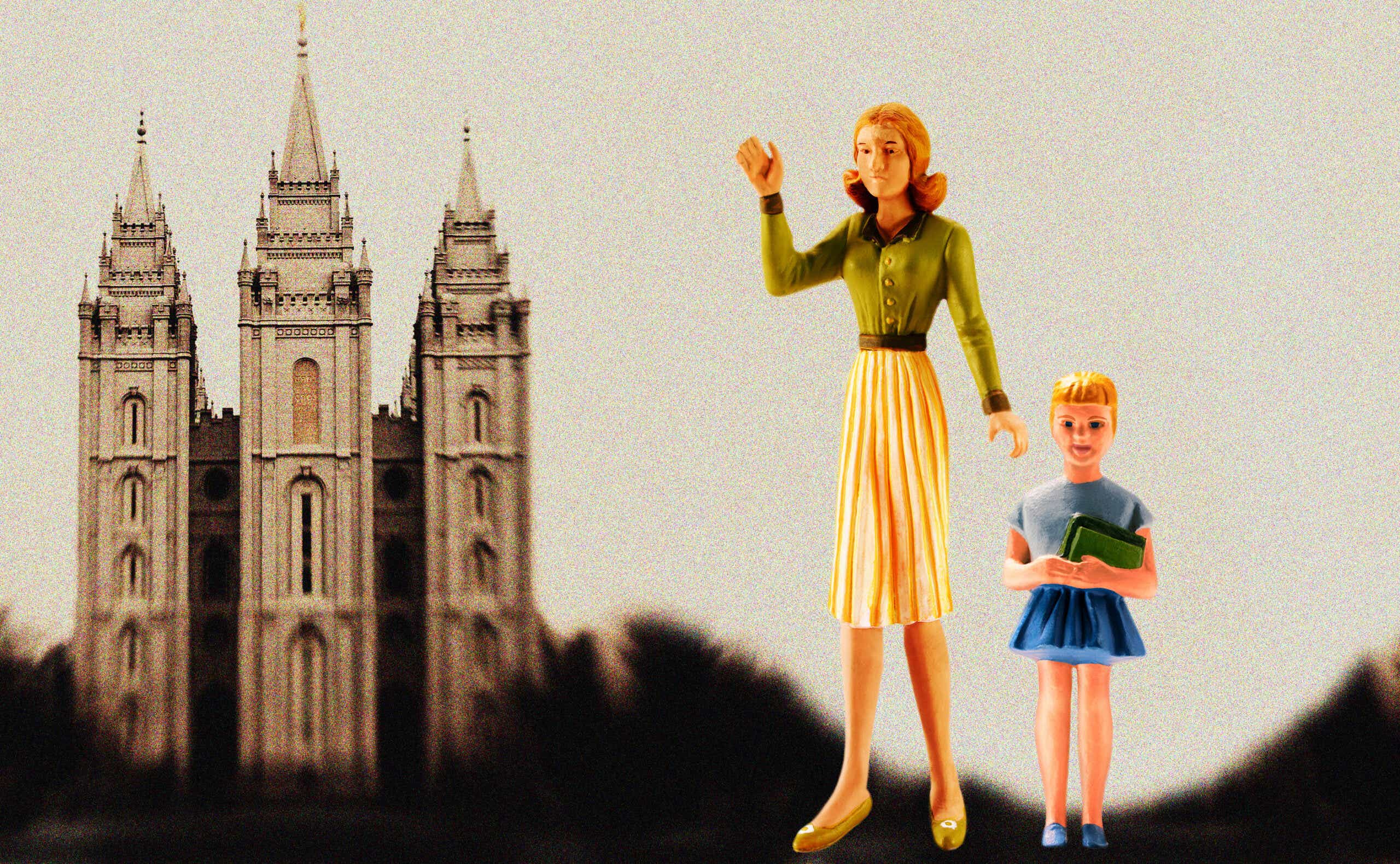

The ideal Mormon woman shows her connection to God in four critical ways. The first three are objectives: She must maintain appearances, be obedient to her husband, and dedicate her life to the well-being of her family. The fourth form of worship is not an objective, but the means by which she accomplishes everything else: She must make it all look easy. It’s not enough for a good Mormon woman to just do her job — she also has to make the job look effortless at every moment along the way. Unlike tasks that often pile up on a Mormon housewife's plate — like folding freshly laundered underwear, carrying out the thankless labor of childcare, or loading the dishwasher at the end of the night — the work of embodying perfection is a chore that never ends. For most Mormon women, it's the performance of a lifetime.

This is what Celeste Davis, an ex-Mormon, told me in a recent conversation. I reached out to Davis to better understand the role that fundamentalist Christian religions like Mormonism play in the tradwife influencer metaverse. “Tradwife” is social media-speak for “traditional wife,” a term which has only recently been coined, and which generally defines a woman who revels in the kind of nuclear family norms we often associate with the 1950s.

A tradwife exists in direct opposition to a feminist. She annihilates all the rough edges of her own messy autonomy in the name of being a more dedicated mother and wife. She forgoes all professional or personal goals outside of the home to free up her schedule for more children, more home-cooked meals, and a daily onslaught of domestic labor. Most importantly — she does all this with relentless cheer.

I’ve been covering tradwife influencers extensively for weeks now, sharing my thoughts on the sudden internet phenomenon from feminist and media literacy perspectives via video critiques on my personal TikTok account. Now I’m delving deeper via this op-ed series, which launched with an explainer of the phenomenon.

Initially, I was skeptical that any significant population of tradwives existed in real life, or if Mormon tradwife influencers like Nara Smith and Hannah Neeleman (of Ballerina Farm) were just a byproduct of the virality economy. This economy works most effectively on short-form video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. It rewards individuals for coming up with new cultural fodder for the chronically online to chew on, regardless of whether what they created online aligns with who they are offline, or if the trend is culturally substantiated by anything other than their desire to be famous.

When I spoke with Davis, she said she didn’t think tradwife influencers were just another social media trend. She knew for a fact that the lifestyle Neeleman and Smith emulate is representative of a certain culture in the real world because she used to be part of that culture. Until four years ago, Davis was a Mormon tradwife. So were all of her friends and family members. In a way, she was technically one of the first types of tradwife influencers: For several years in the early-aughts, she ran a blog where she shared her thoughts about the intersection of marriage and scripture.

“I curled my hair every morning,” she told me. “I wore mascara and dresses every day. My children, my life, all of it was perfect, perfect, perfect — and at the time, I would’ve said to you, ‘Oh, this is just me. This hair, this dress, it’s just who I am.’”

In a way, it was a part of who Davis was. A large portion of the foundational literature about womanhood espoused in fundamentalist Christian communities like the one she was raised in highlights the need for women to be perfect, perfect, perfect.

Proverbs 31 describes in great detail the virtues and behaviors of an ideal woman. She brings her husband “good, not harm, all the days of her life,” and “gets up while it is still night” to “provide food for her family.” This passage might sound theoretical, but for women in the Church, it’s taken quite literally. On TikTok, a Mormon woman told me that girls in her community would aspire to one day be considered a “Proverbs 31 woman.”

“Recovering Evangelical Christian here,” another woman wrote to me on TikTok. “Perfection is a must. Submission is a must. Abuse is rampant.”

Consider, also, The Family: A Proclamation to the World, which functions as a sort of mission statement for how proper Mormon families should behave. “Successful marriages and families are established and maintained on principles of faith, prayer, repentance, forgiveness, respect, love, compassion, work, and wholesome recreational activities,” the document reads. “By divine design, fathers are to preside over their families in love and righteousness and are responsible to provide the necessities of life and protection for their families. Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children.”

Davis and her husband left the church four years ago. Now, she can’t remember the last time she wore mascara, she never wears dresses, and no longer smiles as a way to keep up appearances. The shedding of perfectionism has been, for her, a revelatory coming of age. But she admitted that even she can find it challenging to look back at her time in the church and to try to make any sense of how this irrational drive for perfection was so effective in short-circuiting her life.

“Mormon women aren’t dumb,” she said. “We know that our behavior is kind of ridiculous. I knew, for example, that it wasn’t going to be the end of the world if I skipped putting on mascara before church. But even as I could process that thought and know it to be correct, I still would make us late for service by finishing my makeup. I couldn’t not do the performance.”

Tradwives are frequently criticized for their performance of a kind of femininity that demands repression, and for harnessing a nostalgic and problematic vision of American history. (It wasn't a certain set of "values" that spawned the 1950s homemaker, but a series of wildly effective advertising campaigns designed to sell more refrigerators and stoves.) But for many fundamentalist Christian women, this performance of nostalgia is their reality.

While all of social media is, in the end, some kind of performance, it would be a mistake to group the tradwife influencers with airless online trends. Hannah Neeleman didn't abandon a career in dancing, marry an heir to an airline fortune, and start sharing videos of immaculately herb-decorated sourdough boules because she wanted to go viral. Nara Smith didn't accidentally stumble into the role of an elevated urban housewife with a voice like a kitten who makes ice cream from scratch while wearing a ballgown. They built their brands out of the rock-solid foundation of the religion they were born into. When it came to an outward-facing facade, these women were never going to create anything that wasn't perfect.

Whether people hate-watch Smith and Neeleman, convinced that these videos are a heavily financed charade or watch adoringly because they see them as the ultimate Proverbs 31 women doesn’t matter. The result is the same: People are hooked on the content. You can say what you want about perfection, but you can't deny a simple fact: it sells.

After my conversation with Davis, I found myself wondering if tradwife influencers might be more authentic than other kinds of influencers, rather than less. After all, every influencer portrays a highly idealized and highly unattainable version of being alive. But it’s only the tradwife influencer whose performance of life is every bit as defined by curation and intention as the lives of the demographic she appears to reflect.