“When I die,” my 78-year-old mother announced several summers ago, “you’re only going to remember me for my cooking.”

We were at our family cottage in Manitoba, Canada. My mom had emerged from the kitchen in her usual apron, the one that read “Chief Cook and Bottle Washer,” and was standing over the pre-dinner Rummikub game in which her grandchildren were immersed. They hadn’t seen her coming. She planted her oven-mitted hands on the ample hips around which the apron was tied.

The kids were still in their bathing suits. The boat, life jackets, and inner tubes had been stored for the night. The routine was unchanged: I’d sat at this same table as a teenager with my siblings and cousins, playing the same Rummikub set, the same two Jokers a little thinner than the other tiles, while my mom, separated only by a narrow counter, prepared dinner and opined from the kitchen.

The two eldest grandchildren exchanged wary glances; the younger ones concentrated fearsomely on their tiles. With Grammie, anything could happen next. She might laugh or cry, stomp into her bedroom in a snit, or lean over someone’s Rummikub rack with her own plan for their tiles. A master puzzler, she might even rearrange those tiles herself, announcement forgotten as quickly as considered. Unlike her food, my mom didn’t always taste her words before serving them.

“You don’t know anything about my life before — before this!” The swing of her arm encompassed kitchen, cottage, her life as we knew it.

“You’re in your favorite place in the world, surrounded by people who love you,” I called from the couch, anxious to diffuse this gathering storm. “Why are you thinking about dying?”

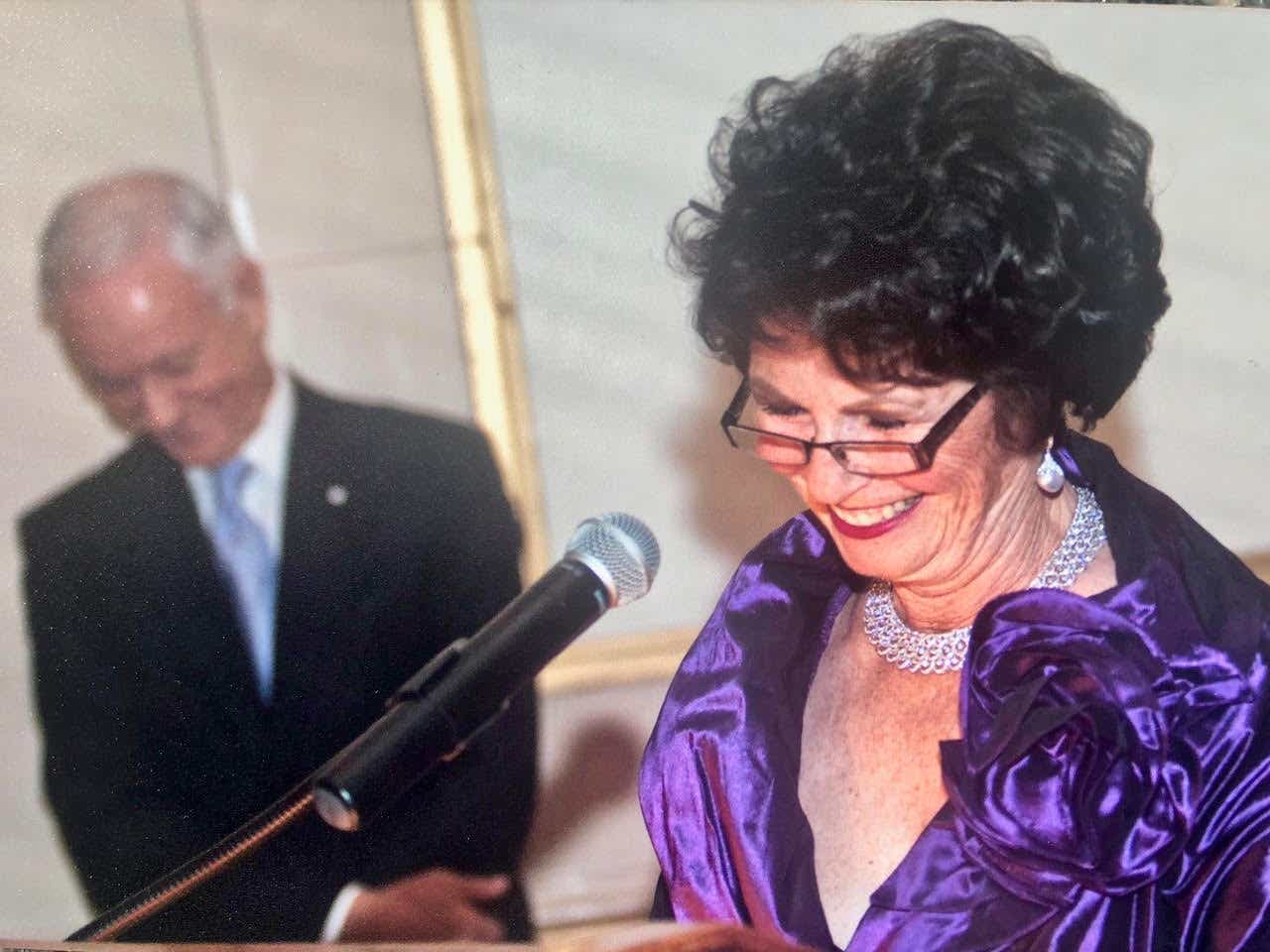

“Because I was trying to talk and no one was listening. I’m not just a pretty face, you know. I managed political campaigns. I was a leader in the Liberal Party. I opened the first packing and shipping store in Canada, for god’s sake.”

“And you still plant your own gardens, and you can hit the ball a mile, and you’re funny. The kids will remember that,” I said. “Take your apron off. You’ll feel much better.”

“My point,” my mom’s chin jutted forward, possibly alarmingly, “is that I’ve done things your kids know nothing about. Real things.”

Ahh. Real things. Feeding one’s family didn’t count.

The reality is that the “real things,” as my mom called her accomplishments, aren’t savored by her family the way her cooking is. Remembering “real things” hadn’t led us as a group to her table, time and time again, like the magical notes of a culinary pied piper.

That summer several years ago, she made it known that she wanted to be seen as more than just the woman in the apron. It’s a struggle I understand.

“I don’t know how you do it,” I said to her earlier this year. “Michael brought seven friends home for the weekend and all I did was cook.” At the cottage, my mom, with help, prepares dinner for up to eighteen of us every night for a week or more. For Yom Kippur in Winnipeg, that number approaches fifty. “Josh,” I said of my husband, “asked me why we didn’t just order in.”

“Anyone can order in,” my mom said. “My friends all do. I’m the only one who still cooks. They aren’t jealous, they don’t want to be doing it anymore. But they do acknowledge me for it. I never brag or anything, but I’m sure they’re all happy I got fat.”

That so many do order in is precisely why I, too, resist it. I don’t even take the middle road — buying a sauce instead of making it, picking up dessert instead of baking it. I don’t use paper plates when it would be appropriate, yet am the first to encourage others to go there, secretly wishing I could practice what I preach. But how often do any of my now-grown kids or their friends, living on their own in tiny apartments, get a “proper” home-cooked meal? My mother’s need to provide in this way has become my need too.

“The cooking weighs on me,” my mom said, “but I like it when it’s done and I can see all that food stacked in the freezer waiting for you kids to arrive. Sometimes I make Dad come look at it with me, just so that someone else can appreciate it.”

She showed me, too — last Yom Kippur holiday, the moment I stepped in the door of my childhood home from the airport. “Come see this,” she said, practically rubbing her hands in glee as I trailed her to the overflow fridge-freezer. Two huge lasagnas wrapped tightly in foil; six dozen cheese blintzes, wrappers handmade, on rimmed baking sheets; a double layer grape Jell-O mold in a Bundt pan; whole filets of salmon in plastic bags; pickerel cheeks ready for frying; and slabs of cinnamon buns to break the day’s fast. For dessert, Winnipeg’s Famous Schmoo torte; pecan-less pecan flan for nut-allergic family members; dark cherry cheesecake, every cherry hand-placed; graham wafer squares under wax paper, and tins of shortbread and sugar cookies, labeled with masking tape in my mom’s tiny handwriting. It was all there, the fruits of her labor of the past several weeks, to be gobbled down in a single evening of gluttony.

“Do you really think cooking doesn’t matter?” I asked, glancing from this bounty to her standing behind me.

“It doesn’t really,” she said, shrugging and shutting the door before adding, “but if I ever stopped, I think they’d all kill themselves.”

My mom’s ambivalence is in no way a comment on the dispensability of her guests, but rather a reflection of the time in which she was most active. In the late 1960s to early 1980s, women’s roles were upheaved and redefined. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published. Gloria Steinem emerged as the voice of women’s rights. In Winnipeg, my mom managed her first political campaign and, against the odds, was successful in getting her candidate elected. Less than a decade and two more campaigns later, she herself was elected as the National Women’s Vice President of Canada’s Liberal Party. In this political and cultural context, cooking for one’s family was not considered important work.

I share my mom’s ambivalence. Feeding my family doesn’t make me feel important or even interesting, yet I love that my kids ask me to cook for their friends when they’re in town, that a meal’s leftovers are gone by the next morning, or are hijacked by people heading home. This last visit, my son took a whole quart of browned rice just for the plane (Grammie’s recipe, it goes without saying).

“And grab some of that banana bread,” his friend texted, still at the airport, “It’s fire.”

The Yiddish word ta’am means not only taste, but also judgment. When a Jewish cook talks about ta’am, it’s as a discernment of flavor and love that, together, nourishes body and soul.

“You cook with such ta’am,” one might say to another. Or, “there aren’t many who have the ta’am you do.”

When my brothers and I moved out, my mom sent us each off with a box full of ta’am — years of recipes, photocopied one-by-one onto cardstock, then cut to size. The lid is cracked, its hinges broken, but I still use that same box, stuffed with recipes I’ve since shared with my own children. Food, security, and love, the great food writer M.F.K. Fisher wrote, are “so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others.”

Though sometimes characterized as an affliction, my mom’s cooking connects her to her grandchildren in a way more real to them than her past achievements. If for this reason alone, her cooking matters.

I, too, think about what makes me matter and how I’ll be remembered — but the accomplishments (and failures) that ultimately define any of us are not ours to decide. I called my mom to share this insight with her.

“That doesn’t stop me from thinking about what my children and grandchildren will say about me at my funeral,” she replied, “not that it matters since I’m not going to be there to hear it.” There was a pause at the other end of the line. “Actually, I will be there, but I won’t hear it.”

She called back the following day, catching me taking dangerous guesses at what people might say about me at my funeral.

“I just want to know,” she said by way of greeting, “How’s my eulogy going?”

“It’s not,” I replied. “I’m too busy working on mine.”

Elizabeth (Beth) Kroft Mondry has an MBA from Northwestern University, a Certificate of Novel Writing from Stanford University, an amazing agent, and a debut novel on submission. She can be found on Instagram and Twitter.