I recently returned home from my freshman year at Columbia, which was, you might imagine, not what I’d expected. It was a year of protest, police, and press — an academic year that seemingly everyone in the world was watching and forming intense opinions on.

Even back in Los Angeles for the summer, my Instagram feed is filled again with news of a third pro-Palestinian encampment at Columbia, bringing all the memories of the past year right back. The thing is, though, people’s perception of what happened at Columbia has rarely, if ever, aligned with my or many of my peers' experiences. Throughout the year, friends and relatives would send me pieces from Breitbart and Al Jazeera about the “terroristic” protesters in the encampments and the “authoritarian” bullies in the administration. Campus was characterized as both a dangerous war zone and a peaceful monastery. Neither of these characterizations were anywhere close to true.

Instead, the year was defined by flashes of insanity amid days of ordinary college mundanity; a student body looking to weather one of the most tumultuous episodes in university history while also passing exams, hanging out with friends, and trying to salvage something like a normal college experience.

To understand what it really felt like being on one of the most highly publicized campuses of 2024, here’s a glimpse at some memorable moments from this crazy year, starting with the first protest after the October 7 attacks in Israel and ending with the final month of school, just after police cleared the first encampment.

Thursday, October 12, ≈4:30 p.m.

In front of Columbia’s Butler Library, a stone pathway bisects two patches of grass. To my left, on the South Lawn East, stand supporters and members of Columbia Students for Justice in Palestine, dressed in the colors of the Palestinian flag, keffiyehs draped around their shoulders. They chant in solidarity with Gazans killed in Israeli attacks.

To my right, crammed inside the South Lawn West fence, students and faculty wave Israeli flags. They stand arm in arm, singing Hebrew songs. Each side is standing for the same simple principle — that human lives should be valued and that no one should live in fear. But to show support with Gazans, you’re funneled into a group chanting for an end to Israel as a whole. To mourn the victims of October 7, you’re directed to a group denying and downplaying atrocities committed by the Israeli Government. Quite literally, to be involved and recognize the tragedies occurring, you must pick a side — one that’s pitted against the other. Being pro-Palestine at Columbia feels like you have to be anti-Israel and vice-versa.

Sunday, April 21, 10:30 p.m.

I’m coming back to my dorm after sitting in on a Columbia College Student Council meeting. My roommate, a British freshman who went to a high school older than the United States, is packing his bags.

“Are you leaving?” I ask.

“My parents want me to come home.”

His parents, first-generation immigrants to England, are terrified of their son walking around a campus as politically charged as Columbia’s. Their perception of America has been shaped by all too frequent news reports of school shootings and police brutality. He knows his parents are being dramatic, but it’s clear he’s scared, too. His folks are particularly nervous that he rooms with me.

“Oscar’s a Jewish journalist,” they said to him. “What if he’s starts getting threats? What if someone throws a grenade in your room?”

To them, from thousands of miles away, Columbia is about as safe as a University in Gaza right now. To hear them tell it, the cops have guns, the students have guns, and he needed to leave as soon as possible. With all finals moved online, the hug we share, before he gets in an Uber bound for JFK, is, in all likelihood, the unceremonious end of my time with my freshman-year roommate.

Saturday, April 21, ≈11:30 p.m.

I fall asleep to chants of “globalize the intifada” and “from the river to the sea” outside my window.

Tuesday, April 22. ≈2:30 p.m.

As I pass through Columbia’s now tightly guarded gates and exit onto Broadway, I walk past a man draped in an Israeli flag talking to a man with a keffiyeh.

“Fucking terrorist bitch,” says the man with the flag. “You wanna kill more kids? Yeah, I bet you do, you fucking terrorist,” he says. All the while, he’s holding a camera up to the man's face, as though documenting his harassment will help his cause. He sees another woman in a keffiyeh walk by, spits on her, and walks away.

Earlier that day, I got an email from a classmate of mine, a fellow Jew, telling me he asked our professor to move our classes online and recommended I do the same. In the email to our professor, he says he no longer feels safe walking across Broadway to the campus Jewish center. For a moment, I question whether he’s being dramatic. I’m Jewish, and so far, I’m unscathed. But he wears a kippah (yarmulke), and I do not. I’ve never worn one. It's not a choice I made expressly to hide my identity, but I'm not going to start wearing one now; I’d be scared to. When I tell my hometown friends I don’t feel “unsafe as a Jew right now,” is it because I’m safe or because I pass as a non-Jew?

Inside campus, things are restrained but tense. Many students support Israel. More do not. But almost everyone is, at most, passive-aggressive toward the opposition, and the campus feels decently safe. It’s hard to feel hateful animus for the opposing side when they sit next to you in calc.

Meanwhile, outside the gates on Broadway and 116th, it’s a different story. Zealots from every side with nothing better to do with their weekdays than yell at college students have gathered — just a few hundred feet on either side of a gate that’s made all the difference in safety and respect.

Monday, April 22, ≈10:30 p.m.

I’m at a Passover seder with my family. Earlier that day, the Columbia Elections Board announced that 76.55 percent of Columbia College Students voted in favor of University Divestment from Israel. I wrote a fairly straightforward piece on the results for the Columbia Daily Spectator, the campus newspaper. After my second bowl of matzo ball soup, I feel my phone buzz. It’s an email from a Columbia Alumni:

U want Jews dead.

Shame on you. Shame.

U are a disgrace. Ignorant.

And u are a micro aggression. ACTUALLY an offense to Columbia And its student body. And to integrity..u biased bad person.

And a lousy reporter.

Your article..the vote.. driven by hate of Jews.

I ask a journalist friend at the seder to read over my article and confirm I’m not secretly a self-loathing anti-semite. She confirms that the story is just a straightforward piece about the results of a poll, and I’d just reported the facts. Still, I’m rattled. “U want jews dead” rings in my head for the rest of the night.

Tuesday, April 23, ≈11:30 p.m.

I’m sitting on a couch in a frat house two blocks off Columbia’s campus, trying to finish a Literature Humanities paper due a week ago. My own procrastination and questionable work habits aside, it seems like everyone’s been having trouble focusing. The noise is constant. From every library, dorm, dining hall, gym, and classroom, there’s a near-constant boom of protest chants, helicopters, and sirens. No one knows how any of this ends. On a campus full of high-achieving kids who pride themselves on almost always knowing the correct answer, the inconclusiveness of it all, paired with the potential for disaster, is unsettling. It’s not exactly an environment conducive to deep, well-reasoned reflections on Augustine’s Confessions.

About an hour earlier, the office of the president of Columbia, Minouche Shafik, sent out an email to the entire “Columbia community,” whatever that means now, saying in so many words that Columbia would call in the NYPD and clear out the encampment for a second time if an agreement wasn’t reached by midnight.

At around 11:30 p.m. I close my computer and walk over to campus with a few friends. One is bringing his nice camera so he can get a shot of the protesters getting arrested for a second time. His final project for Contemporary Civilization is a virtual photography gallery; he thinks a photo will complete the collection. Inside campus, the walkways surrounding the encampment are overflowing. Hundreds of students and a few faculty are clawing for a front-row seat to history.

Wednesday, April 24, 12:01 a.m.

Midnight comes and goes. A few minutes later, leaders of the encampment announced President Shafik had extended the deadline for another 48 hours. There’s a collective sigh. There’s relief for sure, but also disappointment. Is that it? We just go back to our dorms and finish our work now? We’d been gearing up for arrests, and now…nothing? The protesters still want divestment. The university still doesn’t. We’ll all be back here soon.

Tuesday, April 30, 12:45 a.m.

I’m on a party bus coming back from a sorority formal. One of the half-drunk frat boys dressed in an untucked white shirt and loosened blue tie who’s scrolling through his phone looks up at me.

“They took Hamilton Hall,” he says.

“What do you mean they took Hamilton Hall?” I ask.

“I mean the protesters stormed the building.”

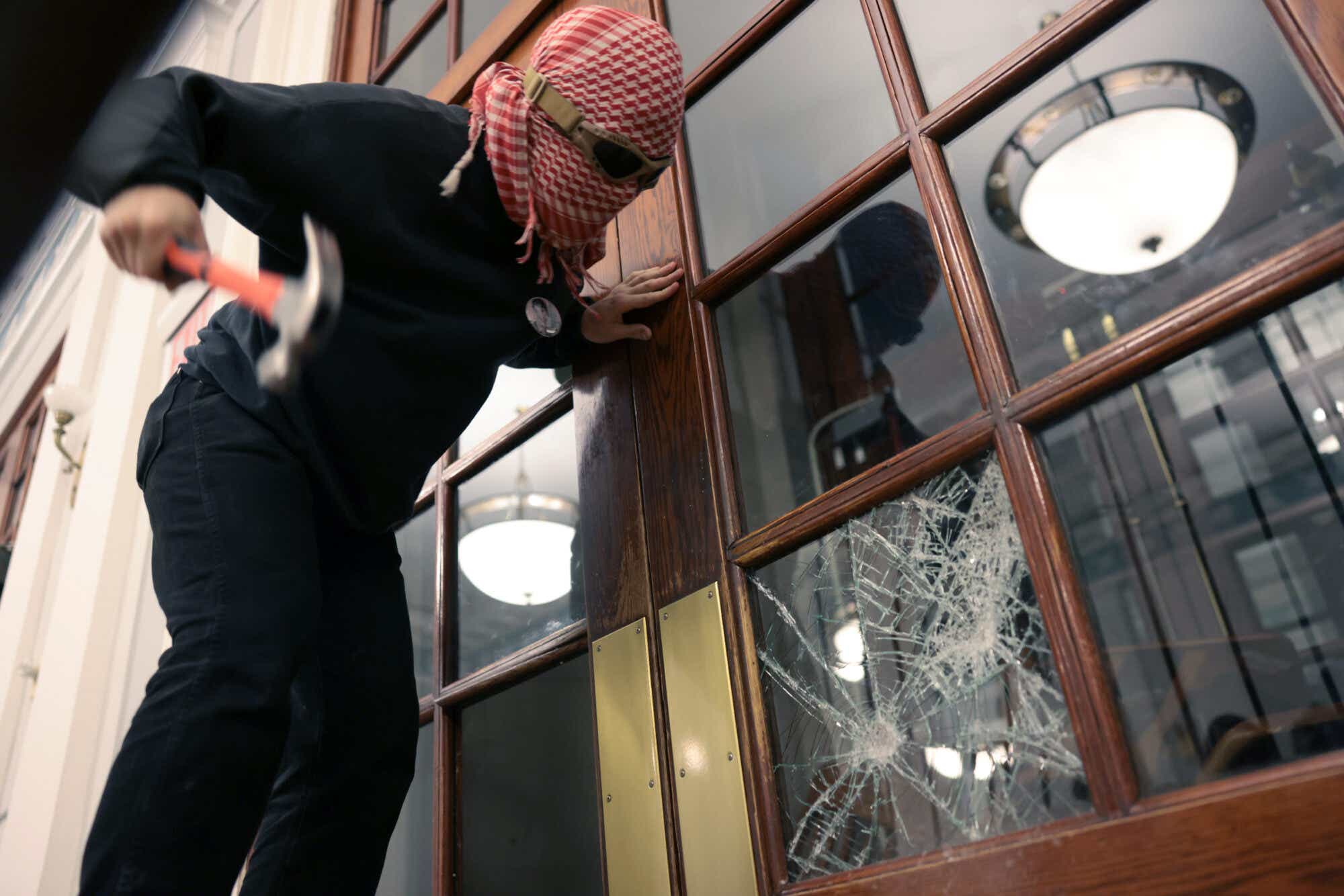

He shows me a photo. Benches and school desks converted into makeshift barricades line the doors. Shattered glass litters the ground. A banner reading “Hind’s Hall” hangs from the second floor, and a crowd of protestors are chanting out in front. Holy. Shit. If the police weren’t coming before, they certainly are now. As word of the escalation spreads through the bus, everyone starts to realize the campus they’d left a few hours earlier in frilly dresses and wrinkled suits would not be the same one they’d return to.

In interviews for the paper over the past few days, I’d been told escalation was imminent; I just didn’t realize what that meant. How didn’t I realize this is what that meant? And how could I be at a party when it all went down?

I get off the bus at the next red light, sprint to my dorm, change into street clothes, don a makeshift Columbia Daily Spectator lanyard, and then sprint to my editor to ask where I can be and how I can help. I tell her I’d just woken up to the news, too embarrassed by the truth.

Tuesday, April 30, ≈9:20 p.m.

I’m standing outside Hamilton Hall as police enter in droves, equipped with riot shields, saws, battering rams, and crowbars. Fifteen minutes later, they leave, a couple of dozen protesters — fellow students — bound with zip ties around their wrists being dragged alongside. Then, the police start arresting protesters outside the building. A cop tells the group of reporters I’m with, “If you do not disperse, you will be arrested.” He repeats the threat, and as I continue to hold my camera, recording the arrests, officers walk toward me. I backpedal away; they walk faster. My footage of the arrests gets grainier and grainier as I get further and further until, ultimately, I cut my losses and walk into a dorm that’s not mine. I’m informed no one can leave the building until further notice.

Wednesday, May 1, 12:00 p.m.

Only students who live on campus — which is all freshmen and a handful of upperclassmen — are allowed there. It feels empty. The lawn where the encampment once stood is empty, and the grass where tents had been torn down now shines a bright green against the trampled dark brown of previously traversed areas. Most finals are canceled. Most dining halls are closed. Within a few days, almost everyone is gone. That’s a wrap on freshman year.

Throughout the year, I couldn’t shake the worry that being at Columbia was robbing me of the quintessential college experience: the college town environment, game days, intramural sports, the stuff you see in movies. Looking back now, though, having seen the movements across the country, I think that my preconceived idea of the college experience might be a thing of the past. Perhaps I’ve lived through the first installment of a new, typical college experience, one which still has remnants of the rowdy atmosphere but is predominantly marked by ever-present activism.

The first encampment was cleared, and students built another the same day. Once that was torn down, many counted it the end of this chapter of Columbia and retreated to their hometowns. But on Friday, in the middle of summer break, Columbia students erected another. Next fall, along with all the normal accompaniments of college life, notebooks and kegs and whatnot, students will no doubt be packing tents, signs, and keffiyehs. The students still want divestment. The University still doesn’t. And as long as there’s conflict between Israel and Palestine, so too will there be protests on campus. At what point does it cease being extraordinary and start to be considered the standard college experience?

Oscar Noxon is a native Angeleno. He was a freshman at Columbia during the 2023-24 academic year, where also served on the staff of the Columbia Daily Spectator newspaper.