Caroline Bissonnette is a journalism and international affairs student at Columbia University who has been on the ground covering the protests against the Israel-Hamas war on Columbia’s campus throughout the year. This is a condensed version of an interview as told to Katie Couric Media’s managing editor of newsletters, Sara Levine.

The tension at Columbia has been mounting all year as students have protested in more and more visible ways, and from my perspective, [these students have been] shut down by the university. Students have gotten suspensions and have been getting doxxed — and not only was their personal information published online, but a lot of them have had trucks with their faces and their names, with horrible slogans written about them, parked in front of the gates here at school. They’ve had hate websites made about them, and they’ve been getting attacked online.

The fact that the university didn’t immediately step in to do anything to support them was devastating. So people have been getting more and more mad all year.

On April 29, Columbia president Minouche Shafik sent an email saying she didn’t want to disrupt classes, exams, or graduation, so the students in the [encampment on the lawn] needed to disperse. That email created a huge hubbub, with thousands of people [marching around the quad, protecting the encampment]. That energy came as a response to the university’s messaging — because the students were threatened with eviction, arrest, and legal proceedings.

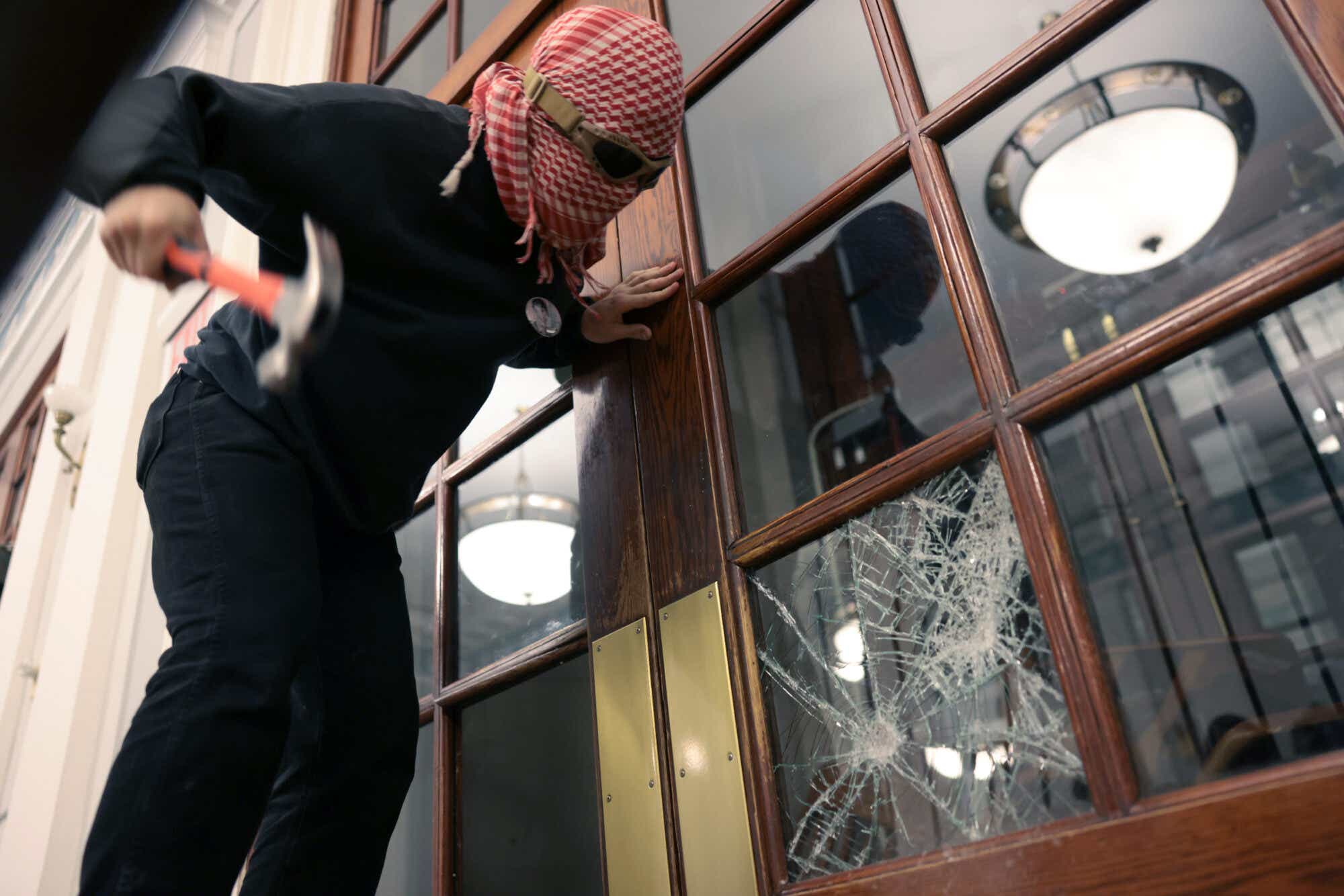

I was there reporting in the early hours of Tuesday morning, April 30. Just after midnight, the students from the encampment decided to escalate their protest, and they took over Hamilton Hall. They’ve barricaded themselves inside. I’ve read estimations of about 60 people being in the actual building itself, with at least dozens more protesters seated outside on the ground in front of all the entrances and exits. It seems like they’re prepared to stay and face whatever consequences might come. They’re dedicated to this cause; they feel they’re in the right in standing against genocide, that they’e doing what’s right for humanity and the world.

The protesters’ goal hasn’t changed: To get the university to divest both its direct and indirect investments from companies that profit from the ongoing war in Gaza.

This escalation didn’t come as a total shock — although it was shocking to actually witness it happen on campus. In her email on Monday morning, President Shafik announced that the university would not meet the demand of divesting from Israel, and [we also learned] that the university would begin issuing suspensions to students still at the encampment past 2 p.m.

From my perspective, this email sparked the escalation in tactics: Suspending students basically gives the university grounds to arrest them for trespassing. Plus, when students are suspended, they lose access to all campus buildings, including the library, dorms, and Student Center, where students have been going to access the bathroom, use electronics, charge their phones, etc.

[On top of all this], these students see this as an extension of a long legacy of protesting at Columbia University. Many of them have studied the protests around the Vietnam War and other [demonstrations], particularly the 1968 occupation of Hamilton Hall. There’s an undergraduate course at Columbia that teaches about the [events] of 1968, and [current] students have modeled their protests on that example, set by previous generations. One of the steps those students took was to occupy Hamilton Hall. I think [this generation] feels they’re following that legacy of activism at Columbia University.