June 21, 2022, was the first day of summer, my 8th wedding anniversary, and the day I found out I had breast cancer.

“You’re due for a mammogram,” my gynecologist said, looking over my medical chart. It was May; I had just gotten a pap smear and was still sitting on the exam table in my pink cotton (open in the front) gown.

“That’s crazy, I just got one!” I told her, with a hint of indignation. I’m normally vigilant, bordering on neurotic, about taking care of my health, especially after my husband Jay died of colon cancer in 1998.

“Actually, you haven’t had a mammogram since December of 2020.”

Wait, what? How could that be? Had the pandemic given me a skewed sense of time? Had it messed with my memory?

“OK,” I told her. “I’ll make an appointment ASAP.”

On June 20, I headed to the office of my breast radiologist, Dr. Susan Drossman, with the intention of recording the screening to share with my audience. This wasn’t exactly new territory for me. You might remember I aired my colonoscopy on the TODAY show in 2000. After that segment, the number of people getting colonoscopies increased by 20 percent. If I had forgotten to schedule a mammogram, this might be a helpful reminder for other people, too.

I handed my phone to a technician and asked if she could film me (in a very PG kind of way) as one by one, my breasts were squished between two plastic trays in a state-of-the-art 3D mammogram machine. Compared to a standard mammogram, the 3D model gives clinicians a more complete view of the breast tissue. Ever the ham, I was cracking jokes and making faces to the camera as I explained what was going on.

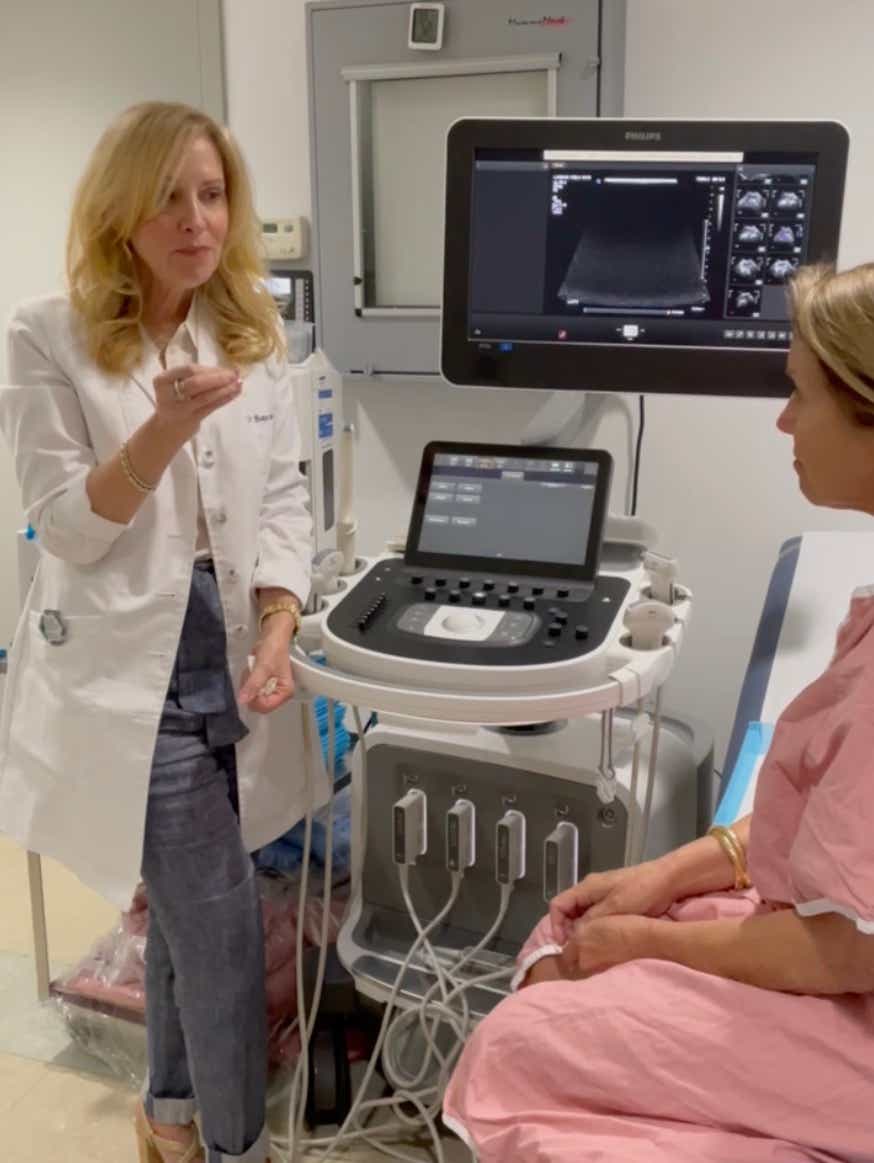

Then I was escorted to another exam room. Because my breasts are dense, I routinely get an additional screening using a breast ultrasound. Dr. Drossman traversed my breasts, sliding the wand-like device over the gooey gel, and then left the room. When she came back, she asked us to stop filming.

“There’s something here that I’d like to check out. It could be scar tissue,” she said (I had a breast reduction in 2016), “but I would feel more comfortable if I did a biopsy.”

Ugh. I wasn’t super stoked about having a needle penetrate my breast to extract several tissue samples, but I was grateful she was being so thorough. I left with gauze in my bra and the promise she would be in touch.

The next day I was at the office, the first time I’d been face to face with my colleagues at Katie Couric Media (KCM) in a very long time.

A text came in: “Please call me in the office to discuss biopsy results. I tried calling you on your cell. Your mailbox is full.” (Typical. My mailbox is always full — with messages going back to 2016.)

When I called back, Dr. Drossman picked up right away. “Your biopsy came back. It’s cancer. You’re going to be fine but we need to make a plan.”

I felt sick and the room started to spin. I was in the middle of an open office, so I walked to a corner and spoke quietly, my mouth unable to keep up with the questions swirling in my head.

What does this mean? Will I need a mastectomy? Will I need chemo? What will the next weeks, months, even years look like?

The heart-stopping, suspended animation feeling I remember all too well came flooding back: Jay’s colon cancer diagnosis at 41 and the terrifying, gutting nine months that followed. My sister Emily’s pancreatic cancer, which would later kill her at 54, just as her political career was really taking off. My mother-in-law Carol’s ovarian cancer, which she was fighting as she buried her son, a year and nine months before she herself was laid to rest.

There were better outcomes for others in my family. My mom was diagnosed with mantle cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which was kept at bay for a decade. My father’s prostate cancer, which was treated with radioactive seeds. My now-husband John had a tumor the size of a coconut on his liver, which was surgically removed just a few months before we got married.

My mood quickly shifted from disbelief to resignation. Given my family’s history of cancer, why would I be spared? My reaction went from “Why me?” to “Why not me?”

But breast cancer — that was a new one; I had practically become an expert on colon and pancreatic cancers, but no one in my family had ever had breast cancer. During that 24-hour whirlwind, I found out that 85 percent of the 264,000 American women who are diagnosed every year in this country have no family history. I clearly had a lot to learn.

I found myself in Dr. Lisa Newman’s office at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. She was warm and gracious and put me at ease right away, despite the fact that I only heard every other word. But I did understand this: “Your tumor is hormone receptor-positive, Her2neu-negative and highly treatable, particularly if it was detected early.”

We decided I would have “breast conservation” surgery, aka a lumpectomy. She would make an incision right around my areola. She said she’d try to make sure any scars would be covered by my bathing suit — the furthest thing from my mind. Surgery would be followed by radiation and medication — specifically, something called an “aromatase inhibitor” I’d need to take for five years.

I didn’t want to call Ellie and Carrie until I had a better idea of my prognosis. Finally, four days after I was diagnosed, I FaceTimed each of them. I tried to be as reassuring as Dr. Newman. Their faces froze in disbelief. Then shock. Then they began to cry. “Don’t worry,” I told Carrie then Ellie, “I’m going to be fine,” trying to convince myself as well as them.

They’d already lost one parent. The idea of losing another was unfathomable.

Surgery was scheduled for July 14.

Before I even walked into the hospital, I had two pre-op procedures. The first at Dr. Drossman’s office, where she inserted a thin metal wire directly into the tumor.

“You’re all set,” Dr. Drossman told me as I left her office, “Just tell Dr. Newman to follow my GPS.” Then it was off to get a radioactive tracer that would find its way to my sentinel lymph node to determine the aggressiveness of the tumor and the course of treatment I would need.

Throughout the process, I kept thinking about two things: How lucky I was to have access to such incredible care, since so many people don’t. And how lucky I was to be the beneficiary of such amazing technology. It made me feel grateful and guilty — and angry that there’s a de facto caste system when it comes to healthcare in America.

I got wheeled into the OR, got a nice dose of Propofol, and woke up in the recovery room. Dr. Newman told me she was pleased with the way things went — she had removed the tumor and the margins were clean. (The pink flowered smock contraption around my breast reminded me of the tube tops I wore in junior high.) No bathing for five days. No swimming for three weeks. Not exactly the summer I was hoping for, but a small price to pay.

The pathology came back a few weeks later. Thankfully, my lymph nodes were clean. But the tumor was bigger than they expected: 2.5 centimeters, roughly the size of an olive. “Kalamata?” I asked. “Castelvetrano? Blue cheese-stuffed?” Whatever fruit it most resembled (yes, olives are considered a fruit), it didn’t change the staging, which was 1A. And I’d later learn my Oncotype — which measures the likelihood of your cancer returning — was 19, considered low enough to forgo chemotherapy.

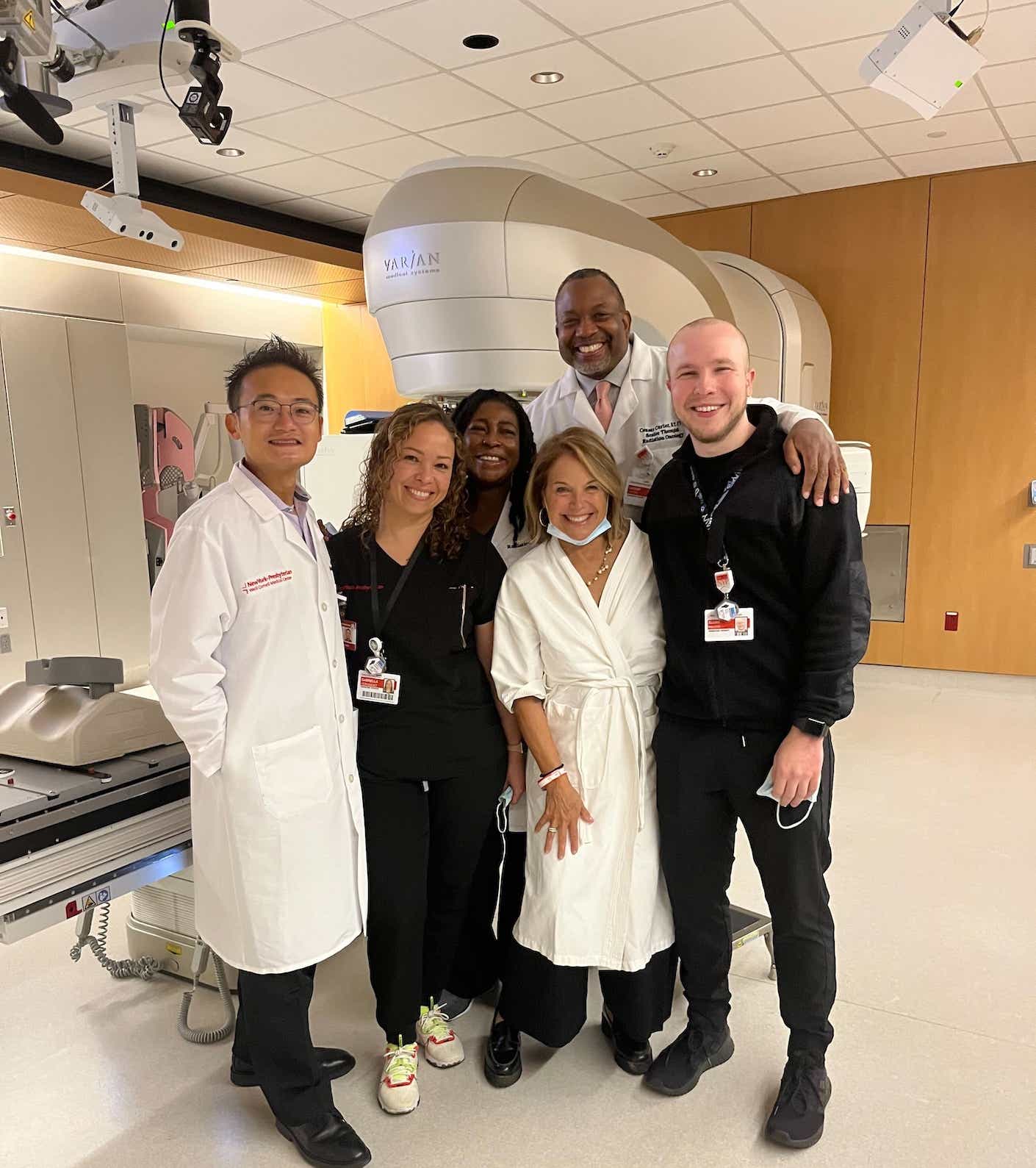

Radiation began on September 7. My radiation oncologist, Dr. John Ng, described it as “dishwashing liquid to wash out any microscopic cells that could be problematic down the line.” Each session lasted about 10 minutes and involved lying face down on a massage-like table with my left breast hanging in an opening, away from my body, so the beams wouldn’t veer off course into my lungs or heart. I looked forward to seeing my whole crew every morning at 8:15. Before each treatment, they asked what music I wanted to listen to — my selections included Ennio Morricone, Stevie Wonder, Bruce Springsteen, Dolly Parton, Taylor Swift, Oscar Peterson, Lake Street Dive, Amy Winehouse, Brandi Carlile, and The Isley Brothers. By the time the second song was finished, I was done. (Maybe I’ll put my radiation playlist on Spotify.)

I was warned that I may be fatigued and my skin may turn a little pink. Yesterday was my final round. My left breast does look like I’ve been sunbathing topless, but other than that, I’ve felt fine.

Why am I telling you all this? Well, since I’m the “Screen Queen” of colon cancer, it seemed odd to not use this as another teachable moment that could save someone’s life.

Please get your annual mammogram. I was six months late this time. I shudder to think what might have happened if I had put it off longer. But just as importantly, please find out if you need additional screening.

Forty-five percent of women in this country (yes, nearly half) have dense breasts, which can make it difficult for mammograms alone to detect abnormalities.

Currently, 38 states require doctors to notify their patients if they have dense breasts. But often that information doesn’t clearly convey the need to have a supplemental screening or this very important fact: The denser your breasts, the higher your risk of cancer. In 2019, the FDA proposed federal legislation that would make the language and guidance more specific, but the agency has been dragging its feet. Let’s get a move on, folks.

Meanwhile, only 14 states and the District of Columbia require insurance companies to fully or partially reimburse patients for the cost of potentially lifesaving breast ultrasounds. That means far too many women are not benefiting from a technology that will allow their breast cancer to be diagnosed early, when it’s most treatable.

When I asked Dr. Drossman about this for one of my upcoming podcasts she told me, “I think it’s disgraceful, to be honest with you. And I think that it’s very poor medicine and it doesn’t make sense, because we have the ability to find more breast cancers with a tool that has absolutely no radiation and is relatively easy to use.”

I can’t tell you how many times during this experience I thanked God that it was 2022. And how many times I silently thanked all the dedicated scientists who have been working their asses off to develop better ways to analyze and treat breast cancer. But to reap the benefits of modern medicine, we need to stay on top of our screenings, advocate for ourselves, and make sure everyone has access to the diagnostic tools that could very well save their life.

During the month of October, we’ll be covering every aspect of breast cancer: the latest diagnostic tools, treatments, and prevention strategies as well as sharing first-person accounts. And of course, I’ll have more on what I’m learning as I navigate my own diagnosis. If you haven’t already, sign up for Wake-Up Call to better understand this potentially lifesaving information.

Until then, we’ve got loads of great content right here about breast cancer, including:

A Beginner’s Breakdown of the Different Types of Breast Cancer

When to Get Your First Mammogram

Do You Have Dense Breasts? Here’s How To Find Out — And What To Know About the Cancer Risks

More Than Mammograms: We Break Down the Different Types of Breast Cancer Screenings

Find Out Which States Have the Highest Breast Cancer Rates

How Mary J. Blige is Fighting Back Against Inequities in Breast Cancer Treatment