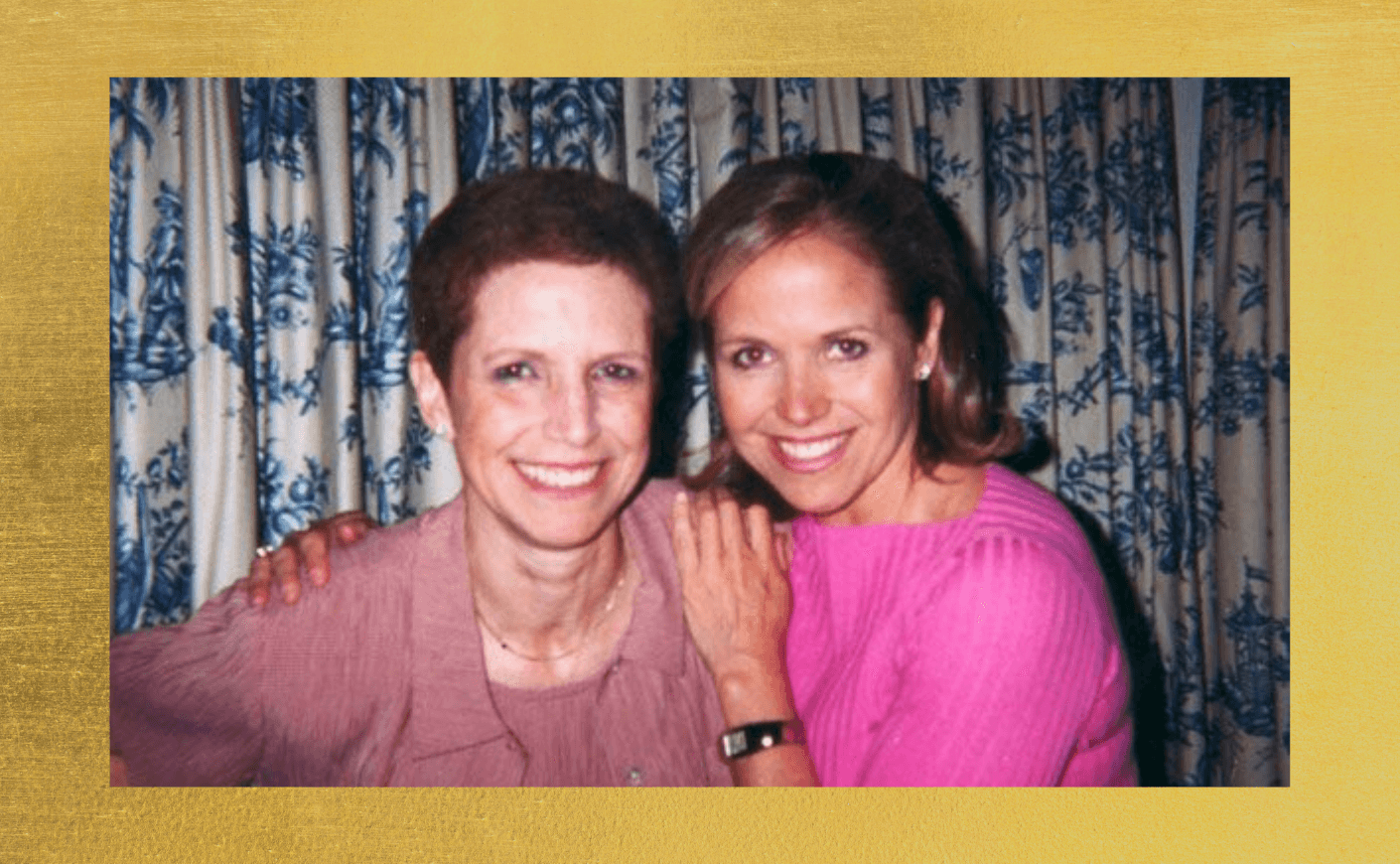

October 18th marked the 21st anniversary of my sister Emily’s death from pancreatic cancer. Her birthday was June 5th; had she lived, she would have been 75 this year. But I don’t want to remember Emily in terms of dates and numbers; there are countless things that come to mind when I think about my sister — and so many ways she is missed.

Emily was the firstborn in our family — my mom’s and dad’s parental test case. That first kid is always the one who seems to have it the worst, the recipient of nascent skills as new parents learn the child-rearing ropes.

Emily was a star. She got good grades, was a cheerleader (before Title IX made sports equally accessible to girls), and dated all the handsome boys. She ran for various student council seats with limited success, despite my dad’s help writing her speeches.

Since Emily was ten years older than me, I viewed her as a slightly exotic, sophisticated, cool creature who was always busy going from one outing to the next. I was just eight years old when she went off to Smith College, but I remember being so proud that she was heading to one of the so-called Seven Sisters, the crème de la crème of higher education for young women at the time.

Emily was serious-minded, driven and a doting big sister. I recently found the sweetest birthday letter she wrote when I turned nine. It was chatty and solicitous, full of questions about my life: “How are you? Don’t you feel like you’re getting old? What presents are you going to get? Be good and polite. I miss you.” (She also teased me about my crush on the paperboy.)

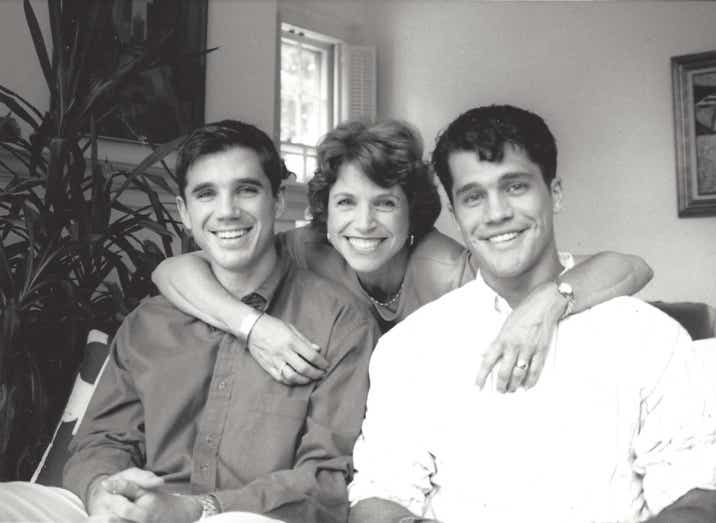

Emily married Clark Wadlow, had two sons, Ray and Jeff, and worked as a writer. She wrote two books: one about women lawyers, the other about divorce lawyers. (Perhaps she wrote the latter because she herself had gotten a divorce from Clark when the boys were little.)

She later moved to Charlottesville after marrying her second husband George, who was the head of cardiology at my alma mater, the University of Virginia. They met sitting next to each other on an airplane. Talk about flying the friendly skies!

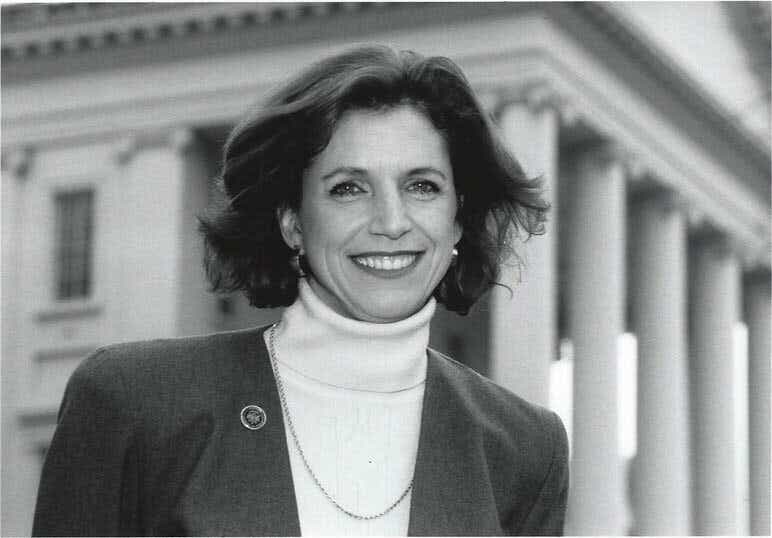

Virginia is where she got interested in politics. She became head of the school board and then a state senator.

I remember taking her shopping in New York City when she was running for the state legislature. She was tall and willowy, and took after my paternal grandmother, so she wore clothes exceptionally well. We had so much fun getting her all suited up for the campaign. It was a funny role reversal: the little sister/stylist helping her older sister perfect a look that fit her intelligence and ambitions.

When my husband Jay died, Emily introduced legislation that required insurance companies to cover screening colonoscopies in the state of Virginia for everyone 50 and over. (The recommended age is now 45.) We were so excited when she was tapped to run for lieutenant governor with Mark Warner.

She was on track, many thought, to become the first female governor of Virginia. Then tragedy struck: Emily was diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer. She had to drop out of the race. “It’s all over my liver,” she told me when she called. And of course, everything changed. In an instant.

Emily went through so many treatments: a chemo cocktail, experimental drugs, and liver ablation at the National Cancer Institute. She was so determined. But she was no match for the disease that would ultimately take over her body. I can barely think about her during those final, gut-wrenching days. When Emily left us, I think a piece of my parents died too.

There’s so much I’ve wanted to talk with her about these past 21 years: I wanted to ask for her thoughts after Charlottesville went under siege by Neo-Nazis on that steamy August day, five years ago. I think of Emily when I see my great-nieces and nephew, and how she would have loved being a grandmother. I think of her when I find myself so despondent about the current state of politics and want to hear her sensible perspective. I wonder if she’d be optimistic about the future of our country.

Now, when I’m in Charlottesville, I make a point to walk by the Emily Couric Clinical Care Center at UVA. Her husband George worked tirelessly to help raise funds for the center — and to get the state legislature on board. He was laser-focused on getting it built to honor Emily.

The aim of the center since it opened in 2011 has been to provide top-notch, state-of-the-art care not only to patients, but also their families. Emily was very grateful for the care she got during her illness, and we wanted to make the center a tribute to her and help “pay it forward” to other patients.

UVA’s cancer program is the only National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in Virginia. So many cancer patients from rural communities don’t have access to quality care. It’s so important that this center is able to treat patients from across Virginia to neighboring states like Maryland, West Virginia, and North Carolina with all of the latest equipment and treatments they might not otherwise have access to.

Pancreatic cancer, like ovarian cancer, is hard to detect early on. It’s often diagnosed when people have symptoms — and when you have symptoms, it often means the disease has progressed. For all stages combined, the 5-year survival rate is only 11 percent. It’s predicted to become the second leading cause of cancer deaths by 2030 (the first being lung cancer).

Since November is Pancreatic Cancer Awareness month, I want to not only pay tribute to my sister Emily, but make sure all of you know about the latest technology and resources available to patients and their families. I’m hopeful about the new scientific strides that are being made; liquid biopsies are offering a lot of promise. (They’re basically blood tests that indicate a sort of nascent cancer cells that can be really helpful in diagnosing the cancer in a very early stage, and can help doctors come up with better treatment plans.)

Technology like the MRIdian system developed by one of our partners, ViewRay, allows more targeted and intense radiation over fewer visits, which can potentially extend the lives of pancreatic cancer patients. It’ll also allow them to spend less time traveling to and from the hospital for treatment. (The Emily Couric Clinical Cancer Center will begin treating patients with this technology starting this month.) And there are new experimental therapies that help bolster the body’s immune system to kill cancer being tested that may become a new tool for treatment in the years to come.

I do know that whenever you say the words “pancreatic cancer,” people often look distraught and deflated. I'm really hoping that we'll be able to address this particular cancer in a much more targeted and helpful way for people who are diagnosed. Right now, it's still very tough.

The reason why cancer advocacy has worked so effectively in pushing science forward is because there are a group of survivors who become advocates. Unfortunately, because there aren't many people who survive pancreatic cancer, the built-in advocacy base isn't there. But my hope is that more people will be able to live with this disease and become foot soldiers in this fight. I wish Emily had been one of them. But I know whenever I think of the strides being made, I always think of her.