Strike captain Taylor Orci explains why all the pain of this work stoppage is worth it.

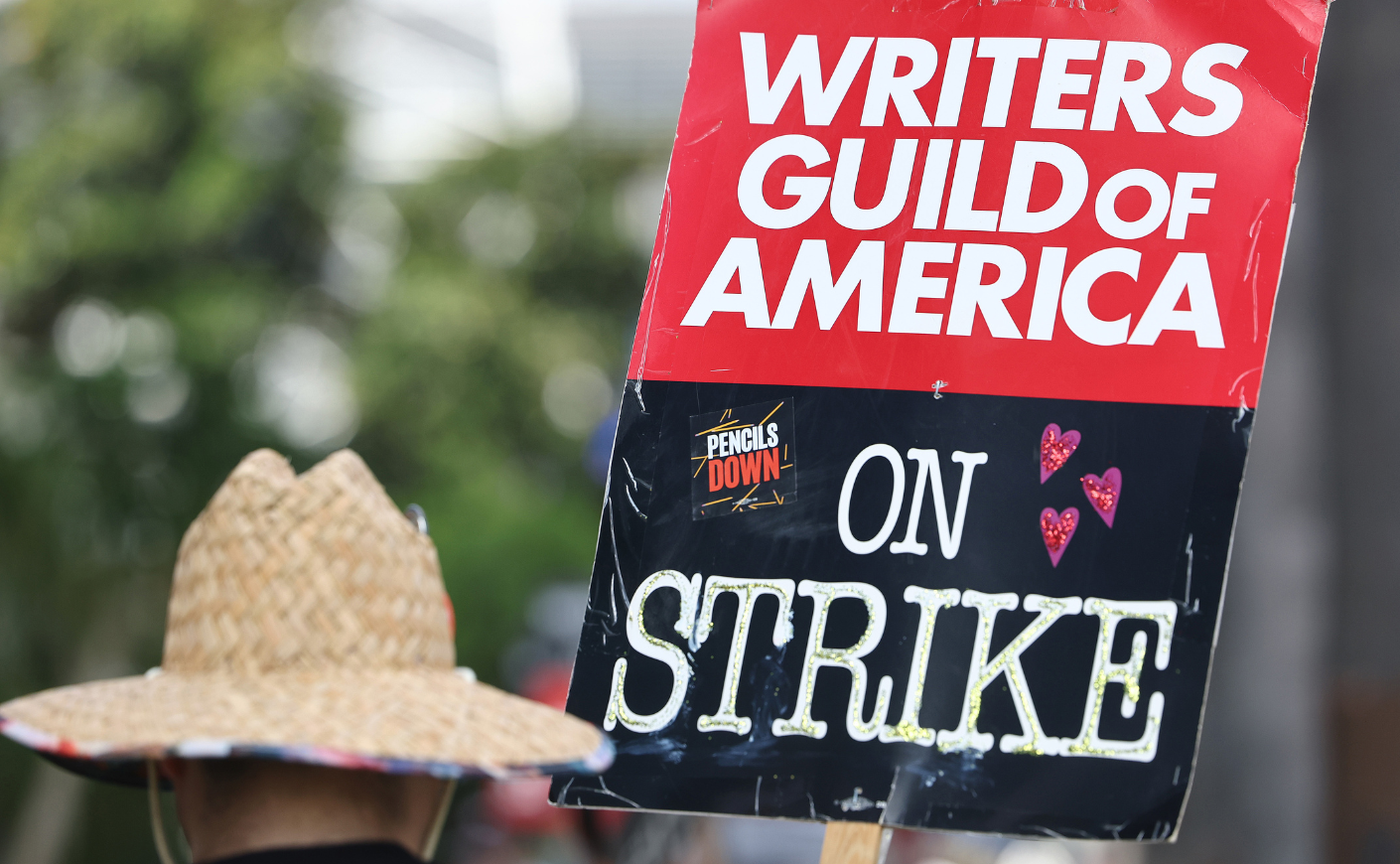

The Writers Guild of America has been on strike since May 2, but after months of picketing in the hot summer sun, its members are still without a deal that would get them back to work.

A conclusion could be on the horizon, as the guild’s leadership and Hollywood’s most powerful CEOs are back at the negotiating table this week. But so far, an agreement has proven elusive — and even if the WGA did end its work stoppage imminently, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) would still need to come to terms with the simultaneously on-strike Screen Actors Guild before film and television production could fully resume.

The writers’ demands include issues of compensation, including revisions to the structure of their residual pay as we move past the age of the rerun and deeper into the streaming era. They’re also focused on the threat of artificial intelligence; they worry that sophisticated chatbots could replace creatives if protective measures aren’t put in place. The guild has so far been committed to holding the line on these asks, but what is the emotional toll of sticking to their principles?

Taylor Orci, a writer whose credits include the Starz series Vida (and who uses they/them pronouns), tells us the process has been “heartbreaking.” Their schedule is typically jam-packed as they juggle multiple projects at once, but these days, all jobs are on hold, and unpaid picketing and organizing are the only things on the agenda. Orci’s family is on food stamps as a result, and even that is — if you can believe it — a bit of a lucky break.

“If you’re striking, you don’t qualify for food stamps,” Orci says. “My last job ended a month before the strike, so I’m fortunate to have qualified for food stamps [before the strike started]. We also don’t get unemployment. That’s actually in a bill we’re hoping Gavin Newsom will sign here in California, so striking workers can get benefits that would really help.”

Orci is one of the WGA’s strike captains, and they called Katie Couric Media after an afternoon of labor action to discuss why these personal sacrifices are worth it, what the public gets wrong about the reality of being a working writer, and why a resolution to this strike won’t actually spell the end of these tense labor debates in Hollywood.

What does it mean to be a strike captain?

It’s about keeping your strikers on the line safe and keeping them on the line period. We do whatever helps engage folks to stay there. It’s organizing themed pickets to keep things fun. It’s about safety, too. We had someone slip, and it was no biggie, but I have ice packs on me. It’s also making sure everyone is hydrated during the hot months. I have a “spray unit” — it’s a household sprayer that I painted with the words “AMPTP tears,” and I use the mist to cool people off.

Are you being paid for this work?

Not at all. None of the captains are being paid. We’re all volunteers.

The strike has shown us that the glamorous idea of being a Hollywood writer doesn’t often match the reality of the job. What do people misunderstand about your profession?

I would imagine people think that a writer has consistent work and that development has some sort of predictable schedule. I’m always working multiple jobs. I might have something in development, something I’m actively writing on, and something I’m wrapping up. But the biggest hurdle in trying to explain the career of a writer is how we get paid. We don’t get paid hourly. Sometimes we don’t even get paid weekly, depending on how our deal is structured. There are a lot of “what ifs.” And when we do get paid, anywhere from 10 percent to as much as 40 percent of our salary goes to people we have on payroll — agents, managers, lawyers. The figure you see is not what we get.

You can’t really predict how much you’re going to make in a year. A lot of writers are just trying to make a living, trying to plan families, and trying to pay our rents. You might get lucky, but that’s luck. It’s like with journalists: You have lots of regular working journalists, and you have one Katie Couric, for instance. But if someone said all journalists are millionaires, you’d laugh. Some people find that level of success.

What has it been like emotionally to go from working three jobs at a time to entering this strike, when the work is at a complete standstill?

It’s heartbreaking. What usually helps me to make sense of our chaotic, absurd world is to write it down. When you’re juggling these different projects, something happens to you during the day and you’re like, “Maybe I’ll think of a story about someone who’s gone through that.” A lot of people have been using this time to brainstorm, but I haven’t been able to. The well is dry.

It’s also very difficult not to see the studios’ outright rejection of our very reasonable proposals as a comment on the profession of writing itself. You just feel threatened.

There has been lots of conflict lately about which shows are or aren’t returning to TV during the strike, like Drew Barrymore and Jennifer Hudson, who both eventually decided not to return after all. What’s your take on how that unfolded?

Drew Barrymore hit hard for me personally. I’m a longtime fan — in junior high I used all my money to buy Rolling Stone when she was on the cover. I have friends who wrote on Santa Clarita Diet, and I’ve met her briefly. She seems free-spirited, like someone who would understand the urgency of this moment. It’s hard to see someone I admire so much use what sounds like union-busting language. Or when you hear David Zaslav [CEO of Warner Bros. Discovery] say “a love for working” is what will end the strike — that sounds a lot like “work will set you free.” Where have I heard that before? That argument is a trick to get labor from people under the idea that it’s going to benefit them in the future.

When Bill Maher first announced his show was returning — which he’s since changed his mind on — he also said “it’s time to bring people back to work,” and that he didn’t want to continue delaying production because it was hurting below-the-line staff.

That logic didn’t make any sense because it didn’t seem like he had a fundamental understanding of what a strike is. It’s about withholding your labor in hopes of getting these studios back to the table because they need your labor in order to profit. That said, it was very heartening to see Drew Barrymore, Jennifer Hudson, and even Bill Maher reverse course. This moment is about learning and showing up as our best selves. We’re all going to make mistakes. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be human.

But here’s what these statements neglect to understand: Our goals during this strike are aligned with these other crews, like the Teamsters and IATSE. Their contracts will come up next summer, and they have issues with A.I. as well. So when you say “let’s get back to work,” it’s like, “Sure — for like a year, buddy.” But these other crews’ contracts will be patterned on writers’ and actors’ contracts, and if we cave now, they won’t get the A.I. protections they need, either. When hosts say they want to get back to work, it ignores the circumstances IATSE and Teamsters find themselves in right now.

Before we got on the phone, you and other WGA members were observing a location where the production team for Dancing With the Stars is working. Can you describe what writers do on a show that people may not consider to be “scripted”?

That’s part of the magic of Hollywood — it’s intrinsic in the profession to erase those lines so you don’t see the trick. But in terms of a competition or reality show, you might have interstitials that a writer is working on, or they’re writing questions, or they’re working on the structure of a segment so it has a beginning, middle, and end. Anytime you’re watching television and someone is having a cathartic moment, there’s a really good chance that a writer is behind it, helping to shape what’s going on.

The focus now is on writers and actors, who are actively on strike, but the work stoppage affects many more people in the business. We’ve even seen stories of restaurants struggling because of it. How widespread are the effects of the strike?

We’re all talking on the picket line, and we’re seeing how other people are being affected. The WGA is organizing fundraisers for IATSE health care. We’re showing up to Teamster rallies. Everybody is hurting right now. I’m hurting right now. Camera operators are hurting right now. Plasterers are hurting right now. But everyone here is knowingly sacrificing because we’re not interested in the short term. We’re interested in the long-term viability of our careers.

The folks we talk to on the picket line aren’t just in our own industry. I’ve talked to nurses, janitors, truck drivers, teachers, and hotel workers. We’re all going through the same thing. We want a fair wage and a middle-class job, not cost-cutting for corporate greed.

Meanwhile, these giant corporations are deciding that they don’t want to pay a fraction of their profits to the people who are making the profits, and instead of meeting our demands, they’re employing crisis PR managers like Molly Levinson to plant stories saying the CEOs are just common-sense people who want to get back to work, or that the WGA is fracturing and writers won’t fall in line. The amount of money that these corporations are sinking into distorting the narrative takes my breath away. People are feeling the pain and struggling to stay in their homes. I have a friend who is watching her mother die in hospice right now, and she’s still trying to be a strike captain from a hospice chair. We are sacrificing so much, and to see these strategists distort this thing that we are fighting for so sincerely is a next level of sinister that I won’t soon forget.

The strike began May 2, and you’re still without a deal after all these months. Some people are questioning whether they can stay in this business longterm. What do you see for your own future as a writer?

I’m not going anywhere. You judge the things you value in life by what you give up to get it. At this moment in my career, I’ve sacrificed so much in order to do what I do. It’s going to take a lot more than this strike to make me quit.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.