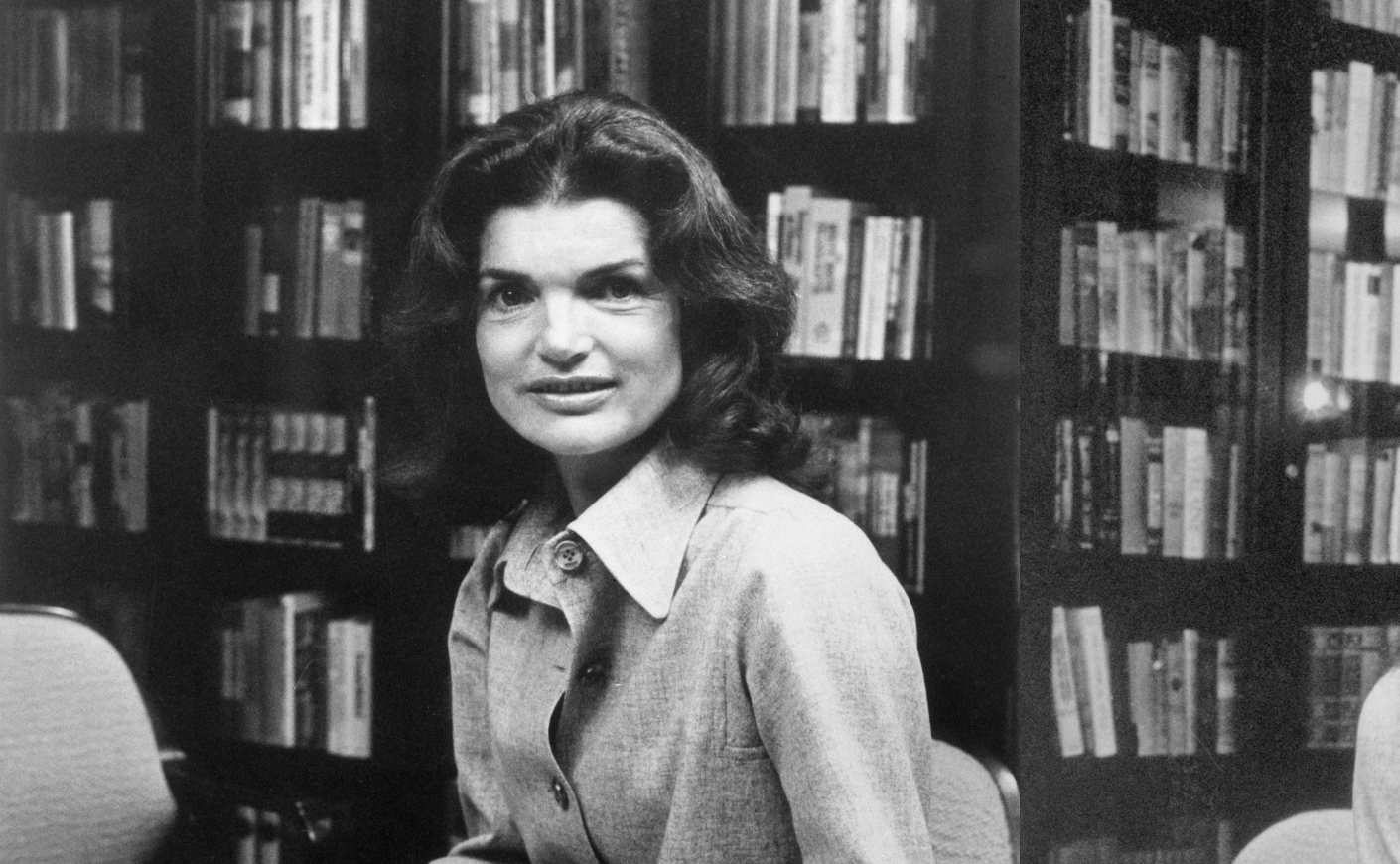

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis tends to be defined by the men who gave her those legendary last names, but she was much more than her marriages — as proven by an unexpected pivot she made at 46 years old.

By then, her first husband, President John F. Kennedy, had been assassinated, and her second husband, Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis, had died of pneumonia. She found herself single again, but now she’d inherited a trust reportedly worth $20 million. She could have done literally anything (or nothing at all). The choice she made was to go to work.

After years of the jet-setting lifestyle that turned her from “Mrs. Kennedy” into “Jackie O,” the former first lady was at a personal crossroads. Her children, Caroline and John Jr., were both teenagers preparing to leave the nest, and even Jackie’s friends sensed her desire for something more.

“I really felt she needed something to get out in the world and meet people doing interesting things, use that energy and that good brain of hers,” said Letitia Baldrige, who had worked for Jackie as her White House social secretary. “I suggested publishing.”

Though taking on a “normal job” seemed like an odd choice for one of the country’s most influential figures, the books industry was a great fit. As a noted lover of the written word who studied at the Sorbonne and earned a bachelor’s degree in French literature from George Washington University, Jackie had both the education and the social connections in New York society to make it happen.

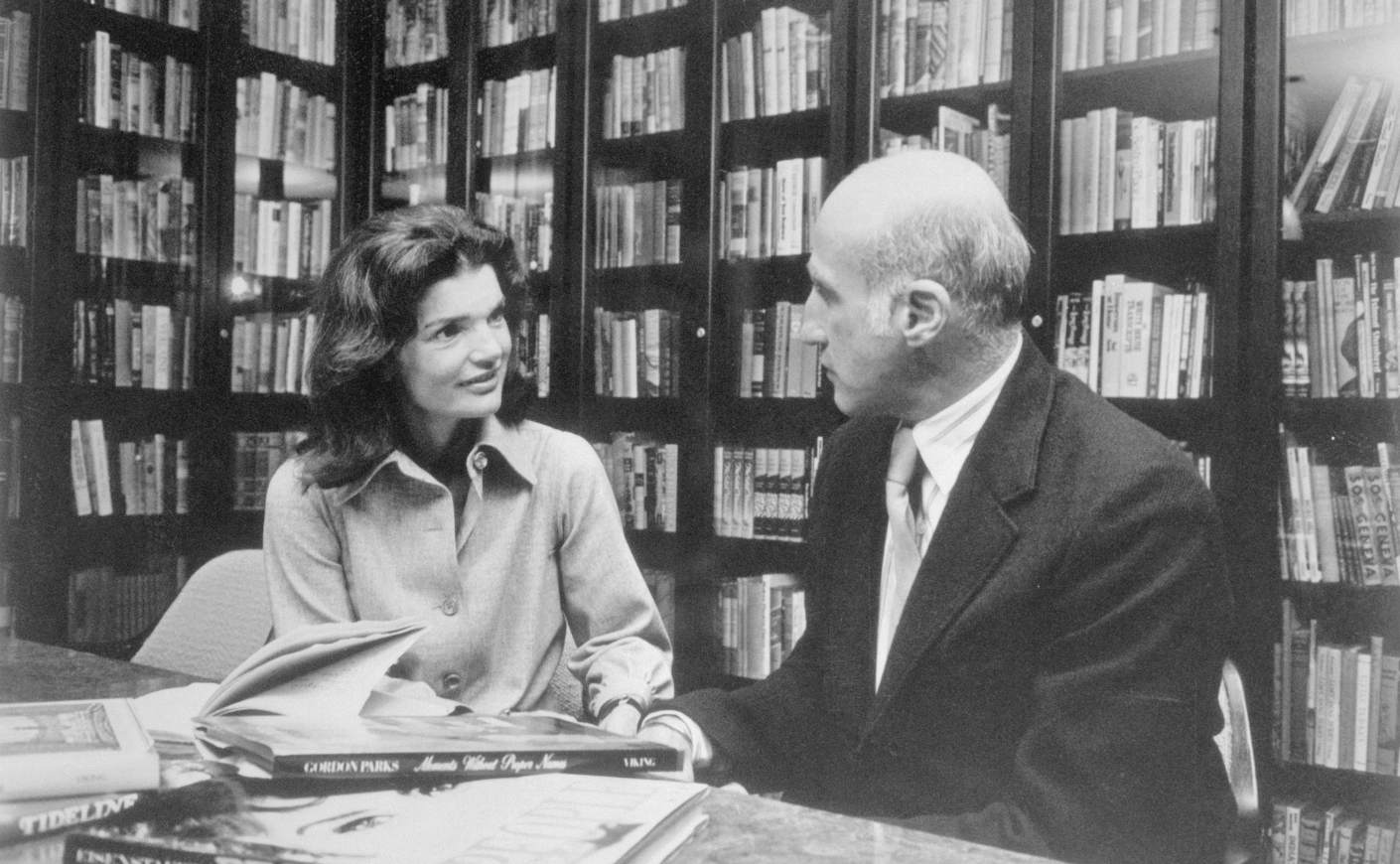

In the summer of 1975, she officially joined Viking Press as a consulting editor. Her primary responsibility was to discover and acquire new titles, for which she was paid $200 a week. That gig lasted until 1977, when she resigned after the company published Shall We Tell the President?, a controversial novel that imagined an assassination plot against JFK’s brother, Sen. Edward Kennedy.

The following year, Jackie signed on for a new job at the publishing company Doubleday. Her starting salary was $20,000 (the equivalent of nearly $97,000 today), and she occupied a small, unassuming office with no windows. She understood how easily her global notoriety could overwhelm her colleagues, and she actively attempted to reduce the intimidation factor.

“She told me she made coffee for people to make them feel comfortable,” said Joe Armstrong, who worked in New York publishing for decades.

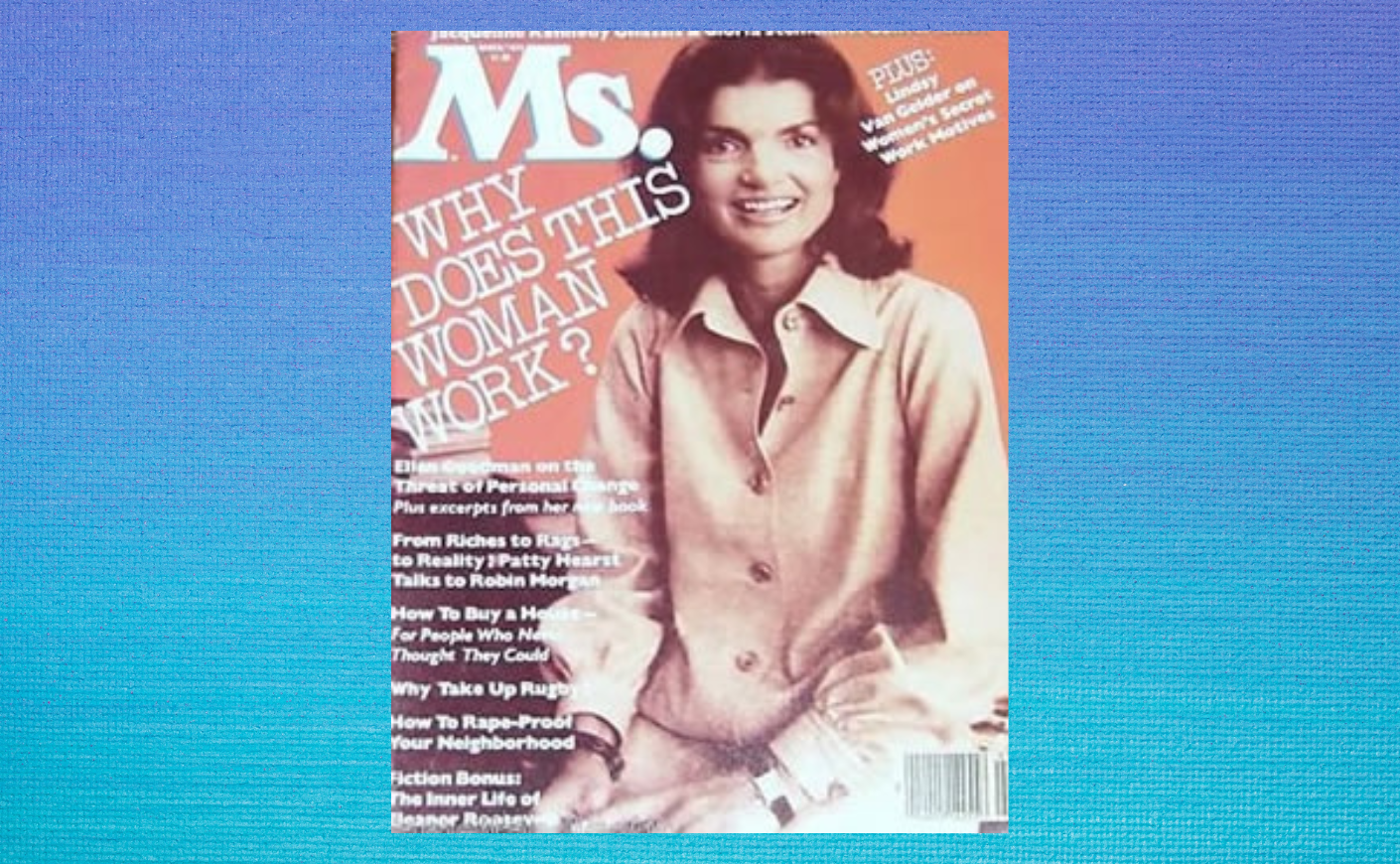

In 1979, Jackie’s book-editing duties caught the attention of Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine, which featured her on its cover alongside the headline, “Why Does This Woman Work?” Inside, Jackie authored an essay about her rationale for becoming a professional when she didn’t have to.

“What has been sad for many women of my generation is that they weren’t supposed to work if they had families. There they were, with the highest education, and what were they to do when the children were grown — watch the raindrops coming down the window pane? Leave their fine minds unexercised?” she wrote. “Of course women should work if they want to. You have to do something you enjoy.”

Jackie worked with Doubleday until her death in 1994. And though she’s more commonly referenced in the modern day for her glamorous relationship with JFK or her influential fashion sense, the books she edited offer perhaps the most personal look inside the mind of a woman who has fascinated the American public for more than half a century.

8 Books Edited By Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Moonwalk by Michael Jackson (1988)

When the biggest global superstar of the 1980s decided to write a memoir, he knew exactly the kind of high-profile editor he wanted: Jackie was “the only person in America who could get [Michael Jackson] on the phone,” according to Stephen Davis, the ghostwriter who penned the book. But she couldn’t seal the deal without navigating one particular pain point: Jackson wanted her to write a personal foreward. Jackie resisted the idea, given that she didn’t include her name in any of the books she edited, but after Jackson threatened to block the publication altogether, Jackie relented.

Published in 1988, after the runaway success of Jackson’s albums Thriller and Bad, this is certainly one of the splashiest titles Jackie ever edited. But it’s also one of the most complicated, largely for what it’s missing: Despite the fact that it tells the life story of one of the most controversial people in American culture, it’s an ultimately benign recounting of his rise to fame. It seems Jackie was aware of that. In a 1985 audio recording, she can be heard lamenting to her art director how little Jackson revealed in his first draft: “Boy, are we going to have to fuel that guy,” she said. She later called the book “a professional embarrassment” that she’d undertaken only to make her bosses at Doubleday happy.

Sally Hemings by Barbara Chase-Riboud (1979)

You may not have heard about her in history class, but Sally Hemings is an important part of the American story. She was born into slavery around 1773 and then “inherited” by Thomas Jefferson — and according to plenty of historians who have conducted deep research, she was also the mother of at least one child fathered by the third president of the United States.

This narrative gets a novel-length exploration in a story that Jackie helped shepherd to the page, a journey that author Barbara Chase-Riboud explored in this essay. She’d been shopping the idea around with zero success, and she expressed her frustration to Jackie during a visit they had on the Greek island of Skorpios. “You simply have to write this book,” the former first lady told her. “You must tell the story of this woman!” Over that weekend together, Jackie asked questions about Hemings, listened carefully, and took notes — and then she became the title’s acquiring editor at Viking Press.

Promised Lands by Elizabeth Crook (1994)

The author of this sweeping novel about the Texas Revolution wrote a moving tribute to Jackie’s work as an editor following her death in 1994. According to Elizabeth Crook, Jackie’s revised drafts were swarmed by the words “cut” and “delete,” along with thoughtful comments about everything from specific word choice (“You do this often — incorrectly use ‘with’ as a connective to cobble together two disparate thoughts”) to bloated prose (“Baby Samuel is so overdescribed it could turn one off babies”).

But working with Jackie wasn’t all easy. Crook recalled that she “often found people more interested in the fact that she was editing my book than in the fact that I was writing it,” leaving her occasionally “disgruntled” about her editor’s star power. But Jackie was also “motherly,” “warm,” and “personal in a professional relationship.” Crooks sums it up like this: “There were times I disagreed with her suggestions. She wasn’t always right. But she sustained my effort, and her editing improved my books in ways impossible to measure.”

Allure by Diana Vreeland (1980)

As the editor of Vogue from 1963 to 1971, Diana Vreeland held significant influence over the flow of American fashion in one of the country’s most aesthetically beloved decades — which included giving advice to the woman who was about to become a timeless style icon. According to the book Empress of Fashion: A Life Of Diana Vreeland, Jackie wrote a letter to Vreeland in 1960 asking for help with what to wear after the expensive European wardrobe she donned at her husband's campaign events got bad press: “I must start to buy American clothes and have it known where I buy them. There have been several newspaper stories about me buying Paris clothes and Mrs. Nixon running up hers on a sewing machine,” Jackie wrote.

Years later, the pair collaborated on Allure, Vreeland’s collection of fashion photography by influential artists like Richard Avedon and Cecil Beaton. It’s a beautiful time capsule of an unforgettable period, and Jackie’s contributions to it offer fascinating insight into how the world’s most powerful cultural figures can be inspired by one another.

My Book of Flowers by Princess Grace of Monaco (1980)

Grace Kelly is yet another of the bigger-than-life names who had known Jackie before they worked together professionally. In 1961, the actress-turned-princess and her husband, Prince Rainier of Monaco, visited the White House for lunch with President Kennedy. Princess Grace later recalled that she and the first lady quickly fell into “woman talk” about their kids: “I remember Jackie was very upset at the photographers who were hounding the children. She was determined that Caroline and John should be able to get in and out of the White House without being pestered.”

Jackie later edited the American version of My Book of Flowers, published in 1980, which explores the history of botanicals and features photographs of the princess’s royal gardens in Monaco.

The Wedding by Dorothy West (1995)

Jackie’s work with Dorothy West, a pioneering writer of the Harlem Renaissance, illustrates the way she fully committed to the projects about which she was most passionate. “Dorothy was very [advanced] in years and was having difficulty getting to the end of her novel,” said Greg Lawrence, author of Jackie as Editor: The Literary Life of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. “Jackie would drive over and spend the afternoons with Dorothy and hold her hand and guide her through her own book. I mean, that's sort of beyond line editing and more conceptual. But it's a heart editing, I suppose.”

The Wedding, West’s final novel, chronicles a prominent Black family in Martha’s Vineyard (the place where Jackie and West had their collaborative sessions together) amid the backdrop of a marriage that prompts complicated self-reflection within the community. The New York Times called it “a beautiful and devastating examination of family, society, and race.”

Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz (English translation published in 1990)

This novel spins a sprawling family saga in colonial Egypt, and it’s the first of a trilogy that continues with Palace of Desire and Sugar Street. Originally published between 1956 and 1957, the series was written in Arabic, so decades passed with the works being largely unknown to the American audience. That changed after Naguib Mahfouz won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988, becoming the first Arab writer to do so.

Jackie immediately sprung into action in hopes of overseeing an English translation. “She would find the Nobel Prize winner in Egypt, Naguib Mahfouz, and suddenly bring him into Doubleday, and suddenly it's bestsellers from this man that no one had ever heard of here,” Lawrence remembered. But that task wouldn’t have been as easy as it sounds for anyone else: Editor Nan Talese recalled that after Mahfouz’s Nobel win, “everyone was after him” — and the head of the publishing house “asked Jackie to call, and she knew why — because she would elicit a response.”

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers (1988)

A book-length examination of scholar Joseph Campbell’s musings on mythology may not seem like a particularly commercial title, but Jackie was enthralled by its premise from the moment she heard about it. Bill Moyers, who worked alongside President Kennedy on the creation of the Peace Corps in the ‘60s, had conducted hours of interviews with Campbell. He and the editor and consultant Betty Sue Flowers had been shopping around a manuscript, only to be met with “radio silence” — until Jackie came calling.

“She comes on the line, and I thought it was one of my students playing a joke. But the voice — you couldn't mistake the voice,” Flowers recalled. “She said, ‘Two of my heroes are Bill Moyers and Joseph Campbell. I hear you have a manuscript. Can you be in New York in 48 hours with 100 black-and-white illustrations and 75 color illustrations?’”

Despite the tight deadline, Flowers managed to make it happen, and the book became a great success. In recounting her collaborations with one of the most famous people of the 20th Century, Flowers added, “I never thought of her, when I worked with her, as a former first lady. I never thought of her as ‘former’ anything. She was totally present right then in who she was.”