I don’t hail from a blue-blooded family. From time to time, I would love to channel my inner duchess, à la Bridgerton (I mean, who wouldn’t?) but this pinkies-up fantasy is not my origin story.

Instead, I proudly share DNA with the farmers who clutch a gun in their dirt-caked hands to defend Ukraine. I’m also cut from the same cloth as the Molotov-cocktail-making grandmother who scoffs at the notion of a quiet retirement. My ilk is the textbook definition of “badassery”: ironclad and steely.

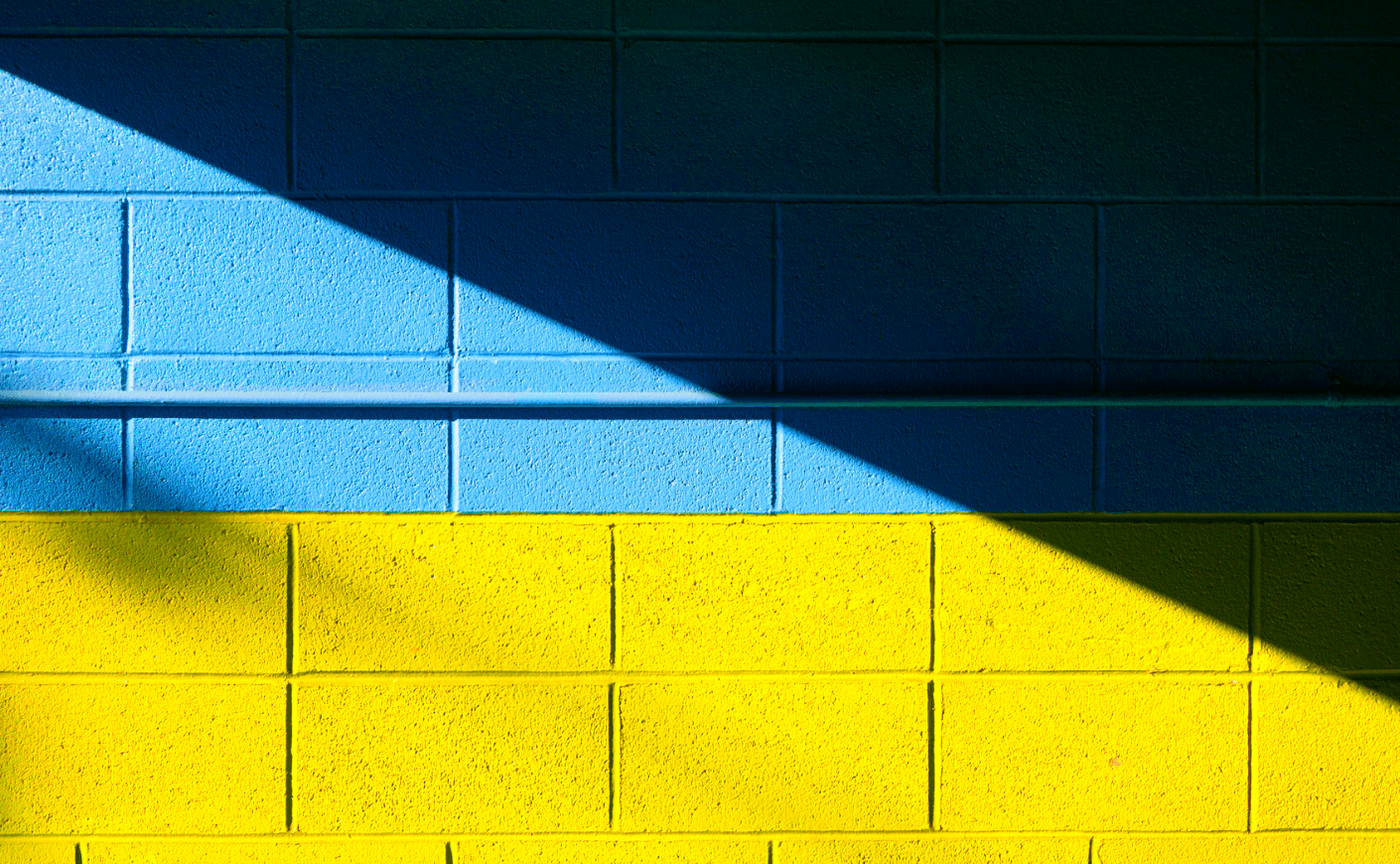

My blood is blue and yellow. Yes, I’m proudly Ukrainian (technically Canadian-Ukrainian, if you really want to be specific).

Today, the word “Ukrainian” is loaded, evoking images that are melancholy and moving, but also gutting and violent. Through the keyhole of the news, the world has seen and heard what Ukraine has suffered in the months since the invasion began.

We’ve heard blood-curdling air sirens which cleared city streets, rendering Ukrainian cities and villages into ghost towns and frigid trenches. We’ve seen mayors kidnapped, staring down the barrel of a gun amid a daylight hostage.

There’s also searing images of Russians brazenly barreling down the doors of two nuclear power plants — the Zaporizhzhia facility and the Chernobyl plant — raising the specter of another cataclysmic nuclear disaster. Or the Russian air strikes that upended a maternity hospital in the beleaguered city of Mariupol as the world watched in bone-chilling horror. Or the 10 million Ukrainians tripping over luggage and landmines, vying for safe passage and spilling over the landlocked borders into Poland, Romania, and Hungary. There’s an unpalatable through-line in all these perturbing news headlines: The Kremlin is agnostic to human suffering. The cries for brokering a tenable peace deal have fallen on deaf ears.

But no one wants my doomsday recount. That’s what the 2022 news cycle is for, right? After 30 minutes of mind-numbingly scrolling through wartime horrors on Instagram and YouTube, I too find myself taking mental laps around an Olympic-sized anxiety pool, my fingers speed-dialing my woefully underpaid therapist. I totally understand.

But this present-day plight is imperative to understanding the blue-and-yellow lifeblood that runs in a Ukrainian’s veins. More importantly, it elucidates why, borrowing the famous words of national treasure and President Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukrainians “don’t need a ride; (they) need more ammunition.” Ukrainians double down and fight.

My grandparents, Olga and Leon Zelkelski, harnessed the same alchemy when they made the wrenching decision to leave Ukraine in 1929. In the dog-eared photos I’ve amassed of them, their demeanor is taciturn and they offer anemic smiles.

In their spit-shine youth, they were salt-of-the-earth farmers who tirelessly tilled the wheat fields (the yellow in the country’s flag) under the brilliant, blue sky (the flag’s blue hue). They relished their simple routine. But this charmed life came to a screeching halt when the Soviet Union ran amok in 1932 to 1933, edging closer to their farm lands. My grandparents luckily turned their heels on the devastation that was to come. They emigrated to Canada, trading dire straits for expansive plots of uncontested land in Alberta, Canada. They narrowly evaded the abject poverty, widespread starvation, and land grabs that eventually began.

The Ukrainian famine — also known as the Holodomor — hit a few years later. Stalin levied a communist concept of collectivization, replacing individually owned farms with state-run collectives. Farmers who refused to cede their land and livelihoods were branded enemies of the state, and 50,000 “mutinous” Ukrainians were incarcerated and deported to Siberia. When the inevitable famine hit, throngs of starving people roamed the countryside. Cemeteries became overcrowded and enormous mass graves were dug. Unlike other famines in history caused by unrelenting blight or dry spells, this famine was created by the Soviet Regime, and claimed the lives of 3.9 million people, a staggering 13 percent of the Ukrainian population.

My parents were resolute in their decision to send us to a Ukrainian school in Toronto, adamant about preserving our heritage. To my now-chagrin, I didn’t give two craps about the Cyrillic alphabet as a child. My only priorities were gawking over the Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake’s matching denim-on-denim outfits, neurotically organizing my beanie baby collection, and learning “The Macarena.” That was, until I met an upstanding Ukrainian teacher who we called панi Helena (Mrs. Helena). I’ll never forget the day she taught us about the luminary poet and Renaissance painter Taras Shevchenko. She would fondly recite his poems to us while we sat, transfixed:

When I die, then make my grave

High on an ancient mound,

In my own beloved Ukraine …

Shevchenko, too, was exiled by the Russian empire. He was indicted for championing the independence of Ukraine, penning poems in the Ukrainian language, and satirizing figures of the Russian Imperial House. He eventually died in Russian exile.

Mrs. Helena, Taras Shevchenko, and my weary grandparents were all instrumental in my formative years. They made me an avowed believer in the undeterred strength of blue and yellow blood. They all hankered to return home, but never did. They all, in their own ways, grieved from an intangible loss of home.

Now scores of Ukrainian refugees are suffering this same fate with no fixed address. They’re displaced and disillusioned by the prospect of a long war. The odds aren’t promising, but if we’ve learned anything about blue and yellow blood, it’s that Ukrainians will take the Kremlin to the cleaners. The Ukrainian army may have brought knives to a gunfight, but they’ve shown their Herculean and Gladiatorial strength at every stage in this war. Despite this, Ukrainians are not impervious to suffering. They are cautiously optimistic, but they need our help. Ukraine is a bellwether for leaders of the free world to step up — to draw a hard line for Russia.

I may sound like I’m speaking of Ukraine with evangelical fervor. And while I ardently love Ukraine, the pain of Syrian, Afghan, and South Sudan refugees is also not lost on me. As refugees across the globe wait for the raging conflict that runs roughshod over their homes and freedom to end, there’s no shock absorbers and support for them. So they slip through the cracks. Instead of watching the images of Ukrainians — or Syrians, or Afghans… — displaced and desperate and being wracked with guilt about our cushy lives, let’s be a bastion of hope and help. Everywhere. Every day. You don’t need to bleed blue and yellow to understand that.

Want to help Ukraine? Here are some organizations doing good on the ground as we speak.