If this year’s Paralympic Games, which start today, are anything like this year’s Olympic Games, it won’t only be the athletes taking center stage. The topic of mental health was front and center at the Tokyo Olympic Games, thanks to athletes like Simone Biles prioritizing her emotional needs over a gold medal. Her actions revealed a major crack in the Olympic foundation — and illuminated issues so many athletes struggle with. To get a feel for how mental health is handled in the Paralympic Games, we spoke to snowboarder and Paralympic medalist Amy Purdy, who celebrates the beauty and "goodness" of the Paralympics, but has also experienced the pressures that come with these games firsthand.

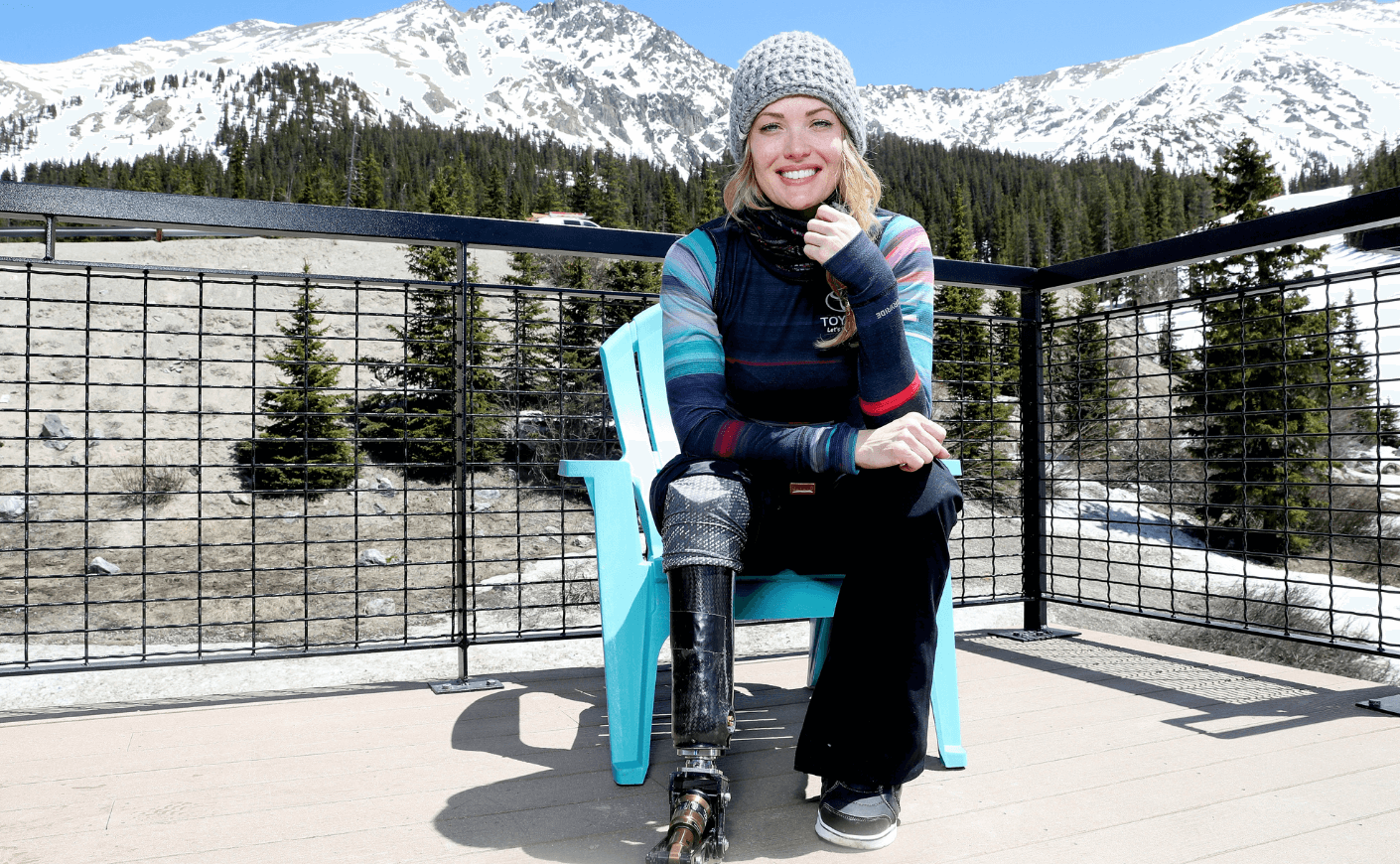

Purdy had her legs amputated below her knees when she was 19, after enduring a bacterial infection called Meningococcal Meningitis. But, passionate about snowboarding, she refused to accept a fate in which she no longer participated in the sport she loved. So Purdy made her own “snowboard feet” by combining different prosthetics, and went on to become one of the top-ranked adaptive snowboarders in the world — and one of the only double-leg amputees competing in snowboarding at a world-class level.

When Purdy went to her first Paralympic Games in 2014, the pressure was on. “I know going into the 2014 Paralympic Games, my mental health suffered hugely,” Purdy shared with KCM. “I put a lot of pressure on myself, because it was the first time snowboarding was in the Paralympics. I was kind of the face of the game at that time: I was on cereal boxes, on billboards, in commercials, on TV.” Months and months of intense public exposure took a toll on Purdy. “Telling the world, ‘I'm going to help show what the possibilities are’ put a huge amount of pressure on me, and my whole life suffered.”

“I was trying to push myself beyond my limits,” she said. “And I had moments where I questioned, Why am I even doing this if I'm not having fun with it? Going into the 2014 Paralympic Games with all this attention was the most stressful time of my life.” She knew she had to make a change the second time around. “Going into the 2018 Paralympic Games, I decided that I wasn’t going to do this unless I was having fun.”

Luckily, that came naturally. “I took the pressure off of myself — I was really there just to figure out what I was capable of,” she said. “There was no outcome I was married to; I didn't have to bring home a gold medal. I just wanted to perform at my best, but I also wanted to feel my best.” The result? Purdy walked away from the Pyeongchang Games with two medals: a silver in snowboardcross and a bronze in the banked slalom. (She also won a bronze in snowboardcross in 2014.)

Purdy believes “no medal is worth your mental health.” That’s why emotional well-being is part of her athlete training with her non-profit Adaptive Action Sports, which she founded in 2005 to help those with permanent disabilities get involved in action sports. She’s currently training athletes for the U.S. snowboarding team who aspire to go to the Paralympics in Beijing in 2022.

Adaptive Action Sports also has sports psychologists work with athletes, since, as Purdy explained, “Mental health is just as important as physical training. You can physically train all you want, but when you step into competition, if you mentally break down and can't handle the pressure, then you're not going to be able to perform.” Purdy’s also been doing a little athlete counseling herself lately, while she recovers from a blood clot that she’s been battling for two years (one that required 10 surgeries to fix — meaning she won’t be competing in the Beijing Paralympics). “I’m not really physically training the athletes, so I sit down with them and talk through the challenges that they're faced with,” Purdy said.

The attention and pressure of the games affect Paralympians differently. “Oftentimes with the Olympics, some of those athletes are used to having a crowd,” said Purdy. “Paralympians don't often get a crowd at our competitions. And then you show up to the Paralympic Games and there's a massive crowd and TV cameras on you,” she pointed out. “So a lot of what we do is visualization — trying to prepare the athletes for all of the different scenarios,” she explained. “If you're mentally prepared for the pressure and all the people watching, you're mentally prepared that you're going to be thrown off your game, and you’re able to visualize how you'll handle that.”

Purdy is, of course, incredibly excited for the Summer Paralympics, and urges viewers to pay special attention to the wheelchair rugby matches — and to a triathlete named Melissa Stockwell. “She was injured in Iraq, and lost her leg above the knee,” said Purdy. “She represented her country when she was in the military, and now she's representing her country as a Paralympic athlete. I’m just so excited to watch her.” The games are high stakes, like any other major sports competition, and Purdy knows the pressure the athletes will face. “I've been there,” she said, “I know what it feels like to be under pressure.” But what’ll undoubtedly shine through, said Purdy, is the skill and prowess of these incredible competitors. Said Purdy, “At the Paralympic Games, the athleticism is just through the roof.”