Last week, on a party-line vote, Democrats combined The Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Right Act into one voting reforms package. If this had passed, it would’ve represented the most significant elections overhaul in nearly a decade. Now that Democrat Sens. Manchin and Sinema have officially sided with the GOP to block changing the filibuster rules, those reforms are doomed.

On Jan. 19, President Biden said he was “profoundly disappointed” that the Senate had “failed to stand up for our democracy.” Martin Luther King III, the oldest son of the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., slammed Sinema and Manchin, saying “they have let down the United States of America. They were given countless opportunities to protect our most sacred franchise, but in the end, they sided with a Jim Crow relic over the voting rights of Black and Brown communities.”

Here’s the story behind this week’s drama, what was in the proposed measures, why they seemed destined to fail — and what comes next.

A Long Time Coming

Congressional Democrats have long pushed to expand voting access with little success. The urgency behind the effort redoubled in wake of the 2020 election, when many Republican-controlled legislatures passed voting restrictions in response to former President Trump’s false claims of voter fraud. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, at least 19 states passed 34 laws restricting access to voting in 2021. These laws have limited voting times and mail-in ballots and raised voter-ID requirements. NPR notes that dozens of states have enacted over 200 measures changing voting laws since the 2020 election.

Republicans blocked Democratic voting rights legislation three times in 2021, arguing that it was a partisan effort that would frustrate local control of elections.

Resistance From The Inside

Every Democratic senator has expressed support for The Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act. But according to the Senate rules at present, it takes 60 senators to end debate and proceed to a vote. As NPR notes this was always going to be an unlikely goal for such a partisan issue in the evenly divided chamber. A Republican vote to block this voting rights legislation, as predicted, prompted an attempt to change the Senate’s filibuster rule.

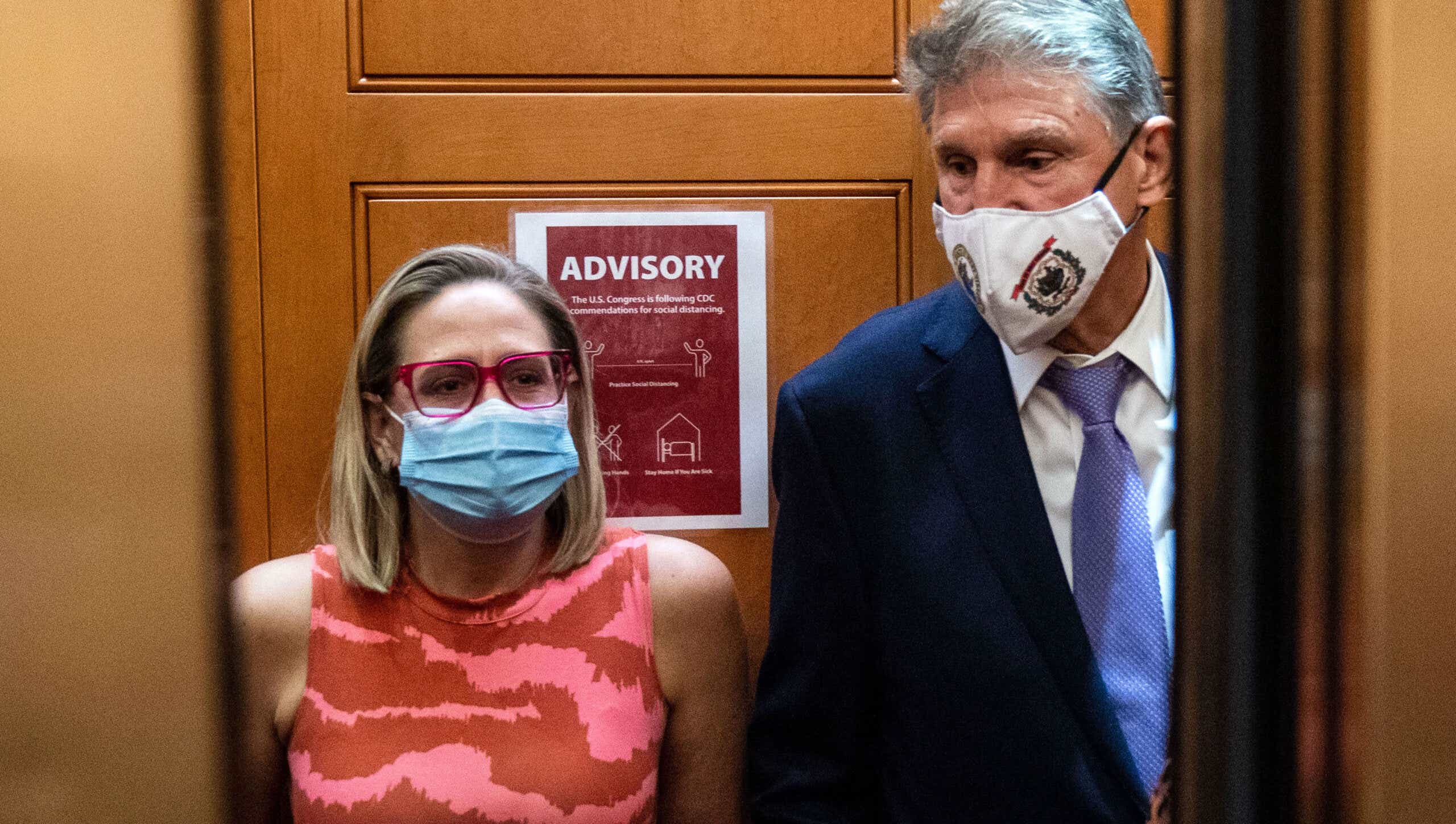

Democratic leaders from President Biden to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer have called for the Senate to change its rules to pass these bills. But two Democrats, Sens. Krysten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, have consistently resisted eliminating the filibuster — and didn’t budge from their position, either when Biden met with Senate Democrats last week, or at crunch time on Wednesday, Jan 19.

Remind Me What The Filibuster Is?

A filibuster is a form of political obstruction available in the Senate which can delay or even prevent the passage of legislation. Its use means that almost all pieces of major legislation need 60 out of 100 votes to pass, as opposed to the simple majority described in the constitution. It was historically used by segregationists to block civil rights reforms.

Rep. Hakeem Jeffries of New York said last week that the filibuster “is dripping in racist history.” Sen. Manchin meanwhile has described ending the filibuster as “the easy way out.”

“I cannot support such a perilous course for the nation when elected leaders are sent to Washington to unite our country by putting politics and party aside,” he said.

Despite her support for the voting rights bills, Sen. Sinema concurred, explaining last week that she would “not support separate actions that worsen the underlying disease of division infecting our country.”

What Was In The Bills?

The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named after the late Georgia congressman, aimed to restore key portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that were struck down by the Supreme Court decisions of Shelby County v. Holder and Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. In particular, it would have reinstated the Act’s requirement that states with a history of voting rights discrimination — mainly in the South — pre-clear certain changes to their voting laws with the federal government.

Other changes to voting laws, like relocating polling places and imposing strict voter ID requirements, would have been subject to preclearance in any state.

The broader Freedom To Vote Act took aim at voter suppression, potential partisan sabotage, gerrymandering, and would also limit the use of “dark money.” Any political action committee that spent more than $10,000 to influence an election would have been required to disclose its donors.

It would have made Election Day a national holiday, meaning that people could vote more easily, and allow states to have early voting for at least a fortnight ahead of Election Day, including nights and weekends. It would also have allowed voting by mail without voters having to provide an excuse, as well as drop boxes for ballots. Voting would have been made more accessible for people with disabilities, and the types of identification voters can use would have been expanded. States would have had to provide same-day voting registration and online registration and make the process of registering at places like departments of motor vehicles easier.

The Freedom To Vote Act would also have strengthened the Federal Election Commission’s ability to investigate charges of campaign abuses. States would also have been required to replace outdated voting machines, and ensure that those in use provide voters with paper records of their ballots.

Both bills enjoyed support from civil rights groups, which agreed with Democrats and their allies that the measures would have prevented states from making it harder for voters — especially people of color — to cast their ballots.

So What Comes Next?

Democrats have been rushing to act while they still just about control both chambers of Congress. Republicans look likely to claim a majority in at least one chamber in the 2022 midterms, which would certainly thwart Democrats’ efforts thereafter.

In the wake of the bills’ defeat in the Senate, Martin Luther King III said: “Despite this setback, we are going to keep fighting for voting rights legislation. This fight marks a new chapter in the King legacy and we will not accept failure. We have set extraordinary groundwork for change and the country will not let this fight end. Ending the filibuster is part of the national conversation in a way it’s never been before — people now know the filibuster is not etched in the Constitution, but rather a tool of suppression, and the voting rights secured by my father are under attack.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer meanwhile vowed that Democrats would continue to fight against voter suppression.

“We will not quit,” he declared on the Senate floor, adding: “We faced an uphill battle. But because of this fight and the fact that each senator had to show where they stand, we are closer to achieving our goal of passing vital voter protection legislation.”

In terms of next steps, the Senate could attempt to fashion a much narrower election-reform bill. This might stand a chance, since some Republicans have expressed a desire to avoid a repeat of the chaos that followed the 2020 U.S. presidential election. In the meantime, the battle over voting rights will shift back to the state level — which in many cases is bad news for those in favor of their evolution and democratization. In several swing states, Republicans are proposing new measures that would make it harder to vote.