The wonders of nature are so vast, they can be hard to believe. In fact, for much of human history, people did discredit the stories of adventurers, because all their talk of strange animals and exotic locations was too difficult to even imagine. That’s why photography has made such a profound impact on the world. With today’s high-definition technology, someone can sit in their house in Wisconsin and access an image that vividly brings to life a tiger prowling through the forests of Southeast Asia. How amazing is that?

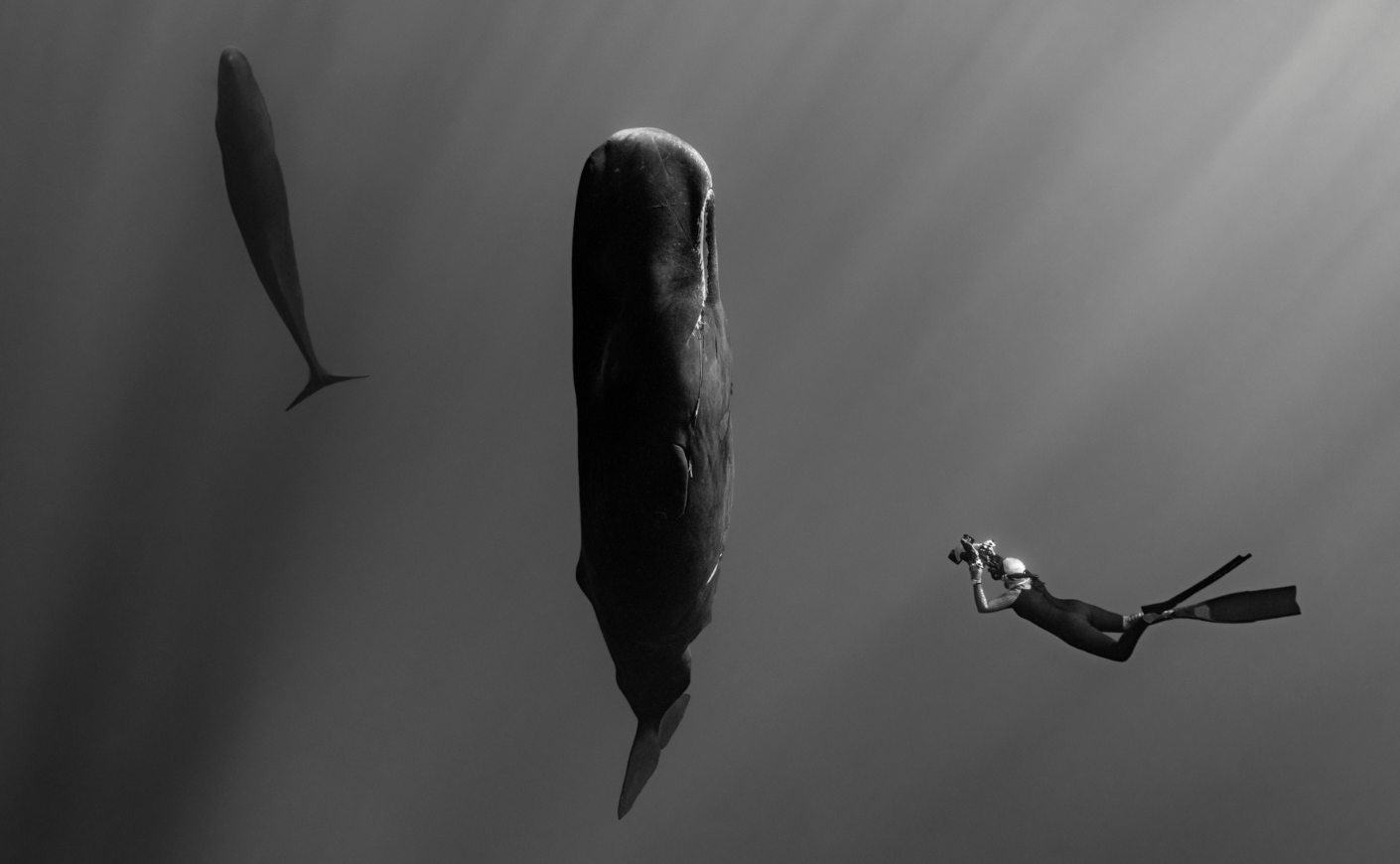

Unfortunately, wildlife photography has taken on new meaning in the age of climate change. And when you remember that the climate crisis is a form of global conflict, then it would follow that environmental photographers like Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier could be compared to wartime photographers. These dedicated environmentalists spend their lives on the “front lines” of the crisis, capturing rapidly changing ecosystems and animals at risk of extinction — and they do it all in the name of carrying more information (as well as a strong sense of urgency) from the ends of the earth all the way into your living room, where you’re sitting on the couch looking at your phone. In fact, they’re so dedicated to fighting the climate crisis that they created their own ocean conservation nonprofit, SeaLegacy, along with fellow photographer Andy Mann. SeaLegacy’s mission is to inspire people to fall in love with the ocean, amplify a network of changemakers around the world, and catalyze hands-on diplomacy through hopeful, world-class visual storytelling.

Below, Nicklen and Mittermeier offer insight into what it’s like to make a career out of capturing such inspiring, striking, and occasionally disturbing images for the world.

You’ve dedicated your lives to capturing the environment and inspiring others. What pieces of environmental art inspired you, at the beginning of your careers?

Paul: The paintings of a local [British Columbia, Canada] painter named Robert Bateman really excited me when I was young. Bateman does very ecosystem-based imagery; he never just paints an animal. It’s always an animal in its ecosystem, in its habitat. If the painting featured an eagle, for example, then you could also see the tree that held the eagle, and the sky and forest surrounding the bird. Those paintings made me want to view the world through an ecological lens. I like the way that ecologists look at an entire cross-section of an ecosystem. It reminds us how everything is connected, and how each organism relies on countless others to function properly.

Cristina: When I was 9 or 10, my father came home with a collection of pirate books by Italian writer Emilio Salgari. The adventures of Sandokan, the Malaysian pirate, were so vividly narrated. The way they described the jungle, the ocean, and all the native cultures who live in these magical places — it truly ignited my young imagination. After those books, I also devoured Jacques Coustau’s The Living Sea and his adventures on the Calypso.

Can you describe a moment in your career when you knew your work had made a difference?

Paul: About a decade ago, there was a big push in Canada to put in roads and open up gold mining in the Peel watershed, a region of untouched sub-Arctic wilderness larger than Nova Scotia. At the time, I was on assignment in the Yukon in 2010, and we were specifically trying to protect the Peel watershed. So much was at stake. At a trial later on, there was a moment when a Supreme Court justice held up National Geographic and pointed at one of my pictures and said, “This is what we’re trying to protect.” That moment makes me emotional, even to remember it; it was a moment where I knew I’d done my job. (Several years later, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled unanimously in favor of protecting the Peel watershed region.)

Cristina: For me, there are two kinds of images that create the biggest impact. There are the images that uplift and inspire, like my image of a sea lion rising to the surface in the Galápagos Islands. So many people reached out to me about that picture, with questions about the animal and the region alike, seeking to understand this exotic terrain. But then I also think about the horrible reminders of the impacts on our planet, like the image of the starving polar bear that I shared in 2017. That photo caused such an uproar, and was featured in TIME‘s Top 10 Images of 2017. It’s a great example of how nature photography can stir people’s emotions and even spark useful forms of controversy.

What motivates you to keep fighting on behalf of the environment, even when it feels like you’re losing the “war”?

Paul: Science is important, of course, but we need to connect with people emotionally, and that’s why photography is so underrated. When you say polar bears are going to disappear in 100 years, you don’t have an emotional, gut-wrenching feeling. But when you see an image of a polar bear starving to death, and you make that emotional connection and realize that each one of those bears is going to die in a horrific way, then people react. That’s why the imagery is important, to remind people. I do worry that there’s been such a shift in the last 10 years from journalistic stories to entertainment. I really hope that Photographer, our new National Geographic series about wildlife photographers, resonates with people and instills the sense of urgency that we personally feel. At the end of the day, if we don’t have a planet, we don’t have humans, we don’t have an ecosystem, we don’t have animals. This work needs to be seen as so much more than entertainment.

Do you have any advice for how people can maintain good mental health while tackling such an overwhelming subject?

Paul: The good thing about having a partnership like the one Cristina and I do is that we take care of each other. When one of us gets down, the other one finds a way to stay positive. I think there are a lot of people in the world who absorb these environmental issues when they’re home alone, and they just end up wallowing in this misery and sadness. So it’s essential to talk about these issues with friends and family, and build a community to hold each other up. Personally, I can get a bit negative at times, but Cristina is such a fierce warrior. She’s always charging ahead, and it inspires me to keep going.

Cristina: There’s the emotional side of it, but what keeps me going is the intellectual challenge of figuring out the solutions. There’s so many pathways to creating impact. We’re trying to dismantle a system that was built when we didn’t know any better, and to fundamentally rethink that system takes a lot of effort. But it can be done — and it is being done. I love that people like Katie want to use her influence to try to push for rethinking these systems. I take a lot of comfort being part of that community of people trying to figure it out.

Want to learn how to make a more positive impact on the planet? Sign up for Ripple Effect, a newsletter from Katie Couric Media which covers the ins and outs of all things climate-focused: news updates, sustainable shopping tips, changemaker stories, and more.