Throughout my career, I‘ve always been drawn to the wildest, most remote corners of the planet. Among them, New Zealand — or Aotearoa, as the Māori call it — stands apart as one of the richest marine ecosystems I have ever had the privilege of exploring. Ninety-three percent of this island nation is ocean, and much of that territory contains species found nowhere else on Earth. Caring for that much ocean is an immense responsibility, and in recent years, New Zealand has been falling dangerously behind.

Looking for answers, I joined my partner, SeaLegacy co-founder Cristina Mittermeier, and our crew aboard our boat, the SeaLegacy 1, in New Zealand early last year. We wanted to better understand the threats facing these seas, and we knew there was one person who could show us the way.

A firsthand look at the devastation

Steve Hathaway, co-founder of Young Ocean Explorers and a professional underwater cameraman, has spent his entire life with New Zealand’s ocean as his backyard. Under his guidance, we set out to our first site, where he had been diving for over 30 years.

We slipped beneath the surface, and as we descended, all I saw at first was bare rock — and then it became clear.

Massive clusters of sea urchins littered the seafloor. Steve had brought me to an “urchin barren,” and this was one of the most devastating examples I had ever seen. According to him, it was once a flourishing ecosystem, but the urchins had stripped it bare, reducing a thriving kelp forest to rubble. Most of the wildlife that once depended on the kelp was gone, replaced by a barren desert beneath the waves.

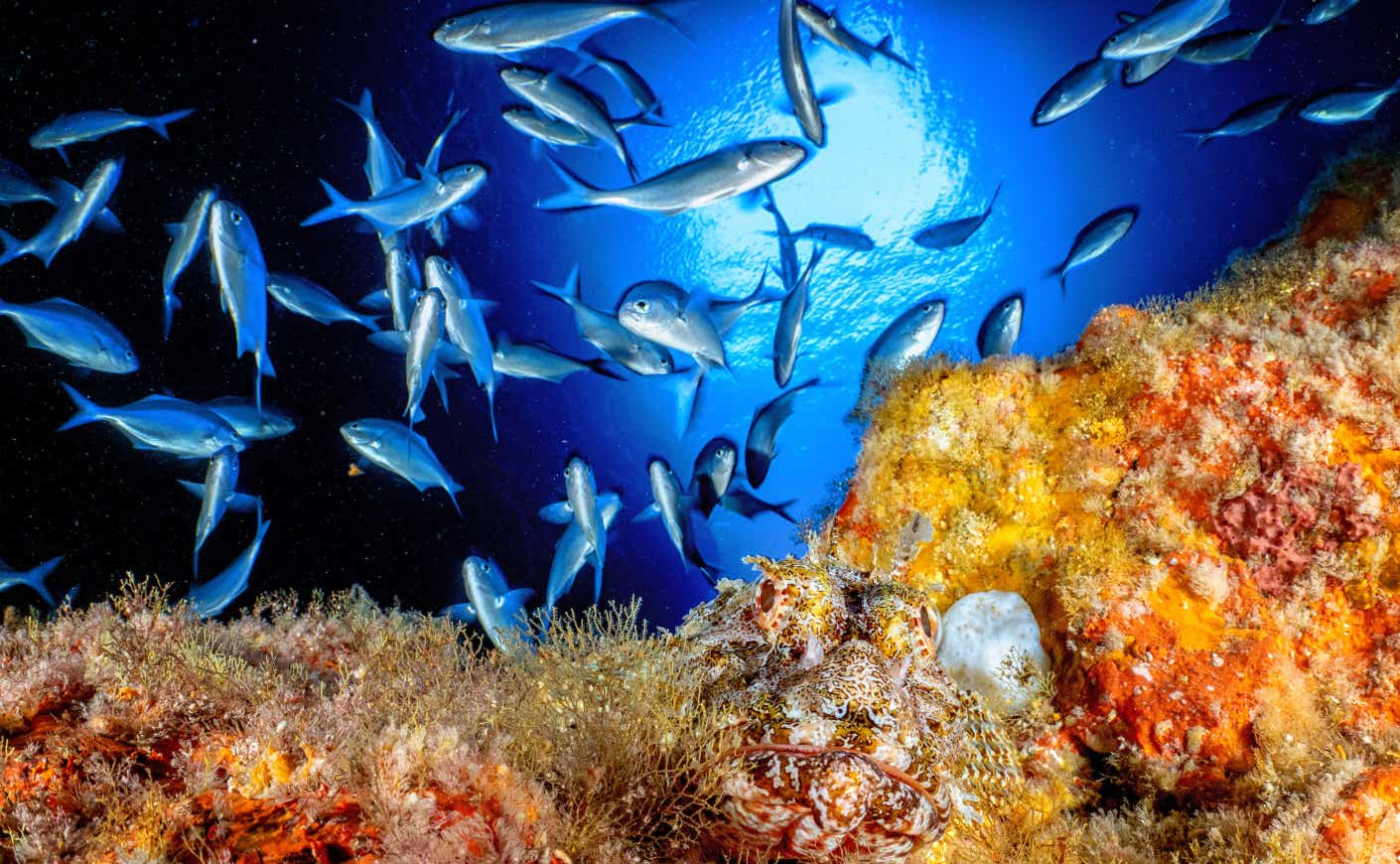

Leaving the decimated seafloor behind, Steve then took me to the Poor Knights Islands — a world-class dive site. The difference was shocking, like stumbling across an underwater rainforest. Golden kelp fronds swayed in the current as thousands of fish in every imaginable size and shape threaded through the canopy — even a bronze whaler shark cruised by with its own entourage of fish. I felt as though I had stumbled into one of the ocean’s last great treasure troves of biodiversity.

Still, I couldn’t shake the pit in my stomach. This was what the first site should have looked like. The only difference? The Poor Knights Islands are fully protected as a no-take Marine Protected Area (MPA). The first site isn’t.

In healthy ecosystems, predators like snapper and rock lobster (crayfish) keep urchin populations under control. But these are big target species for fisheries, and when the predators are overfished, urchins multiply, stripping these underwater rainforests to the rock. And when the kelp goes, everything else goes with it.

The Poor Knights Islands should be an example of how the ocean around New Zealand is supposed to look, but sadly, it is now the rare exception. New Zealand’s track record, especially compared to its global commitments, paints a troubling picture.

A mirage of ocean management

In 2022, the United Nations set the necessary and long-overdue goal to protect 30 percent of Earth’s land and sea by 2030. New Zealand markets itself as a global champion of conservation, and on land, that’s true. Around 32 percent of its land is already protected. But how much of its ocean, which makes up 93 percent of its territory, is fully protected from extractive activities?

Less than 0.5 percent. I was stunned when Steve told me this sobering fact.

On paper, New Zealand claims about 30 percent of its ocean is protected in some way. But definitions of marine protections have been stretched so far that many of them are meaningless. Most of their MPAs still allow industrial fishing. The “protected” part is that only certain activities, like bottom trawling, are restricted.

These are classic examples of “paper parks” — MPAs that look good on paper but fail in practice, whether it’s weak regulations, poor enforcement, or no protection at all. And you can find them all around the globe.

Politicians lean on these watered-down definitions of protection so they can claim environmental targets are met without upsetting fishers or industry. Both sides are satisfied, but nothing actually changes.

Fully protected, no-take MPAs are another story. They allow a safe haven for ecosystems to recover. Over time, this abundance overflows beyond the boundaries of the reserve, called the spillover effect. Far from being bad news for fishing communities, well-managed MPAs can replenish what’s been lost and sustain healthier fisheries in the long term.

We’ve seen it work elsewhere. One of the best examples I have ever witnessed is the Revillagigedo Archipelago in Mexico. Declared a no-take marine park in 2017, it became the largest fully protected MPA in North America. At first, some local fishers resisted the change. But within just a few years, biodiversity returned as fish populations spilled over the boundaries, boosting stocks in surrounding waters.

This is the kind of leadership New Zealand should be showing. With one of the world’s largest Exclusive Economic Zones, they carry an enormous responsibility. But right now, they’re almost dead last.

What can we do?

It starts with shifting how we see MPAs from restrictions to investments in our future. Changing mindsets isn’t easy, but there is hope. Steve Hathaway and his daughter, Riley, are already achieving the impossible through Young Ocean Explorers. Using stunning footage and educational tools, they connect kids to the ocean, teaching them that it’s worth exploring — and worth protecting. These kids will grow up to be the ones voting on whether to protect their oceans for future generations.

That’s why, in collaboration with the 100 for the Ocean campaign, SeaLegacy produced a short film about Young Ocean Explorers and their impact. It’s free to watch, and I recommend it to anyone who wants to bring this kind of change to their own community.

What I saw in New Zealand moved me. In a single week, I went from lifeless seafloors stripped bare by sea urchins to thriving kelp forests overflowing with fish, sharks, and color. That stark contrast of devastation and abundance makes it impossible not to see the path forward. Fully protected no-take MPAs work. We need more of them in the world — and they have to be real.

We’re already past halfway to 2030, and New Zealand has a long way to go.