Having studied marine biology and worked in ocean conservation, I’ve often heard that the biggest barrier to solving environmental problems isn’t a lack of knowledge, but a lack of political will. I’ve come across that idea in lecture halls, in scientific papers, and in conversations with conservationists like Cristina Mittermeier, a mentor and co-founder of SeaLegacy. So when she asked me to attend the annual meeting of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) this July, I said yes without hesitation.

I thought I understood what a lack of political will meant. But watching it play out in real time, where science meets diplomacy, was another thing entirely.

I attended as part of the youth delegation with Sustainable Ocean Alliance, representing SeaLegacy at the ISA’s 30th session — a meeting that could shape the future of the deep sea. I arrived with cautious optimism. The ISA is tasked with regulating mining in international waters and protecting the marine environment. But the reality was far more complex: a process slowed by political hesitancy and corporate pressure.

If you're unfamiliar with the ISA or the controversy around deep-sea mining, you're not alone. For years, this UN body operated in obscurity. But with rising interest in mining the seafloor — despite serious ecological risks — it’s quickly becoming one of the most hotly debated issues in ocean governance.

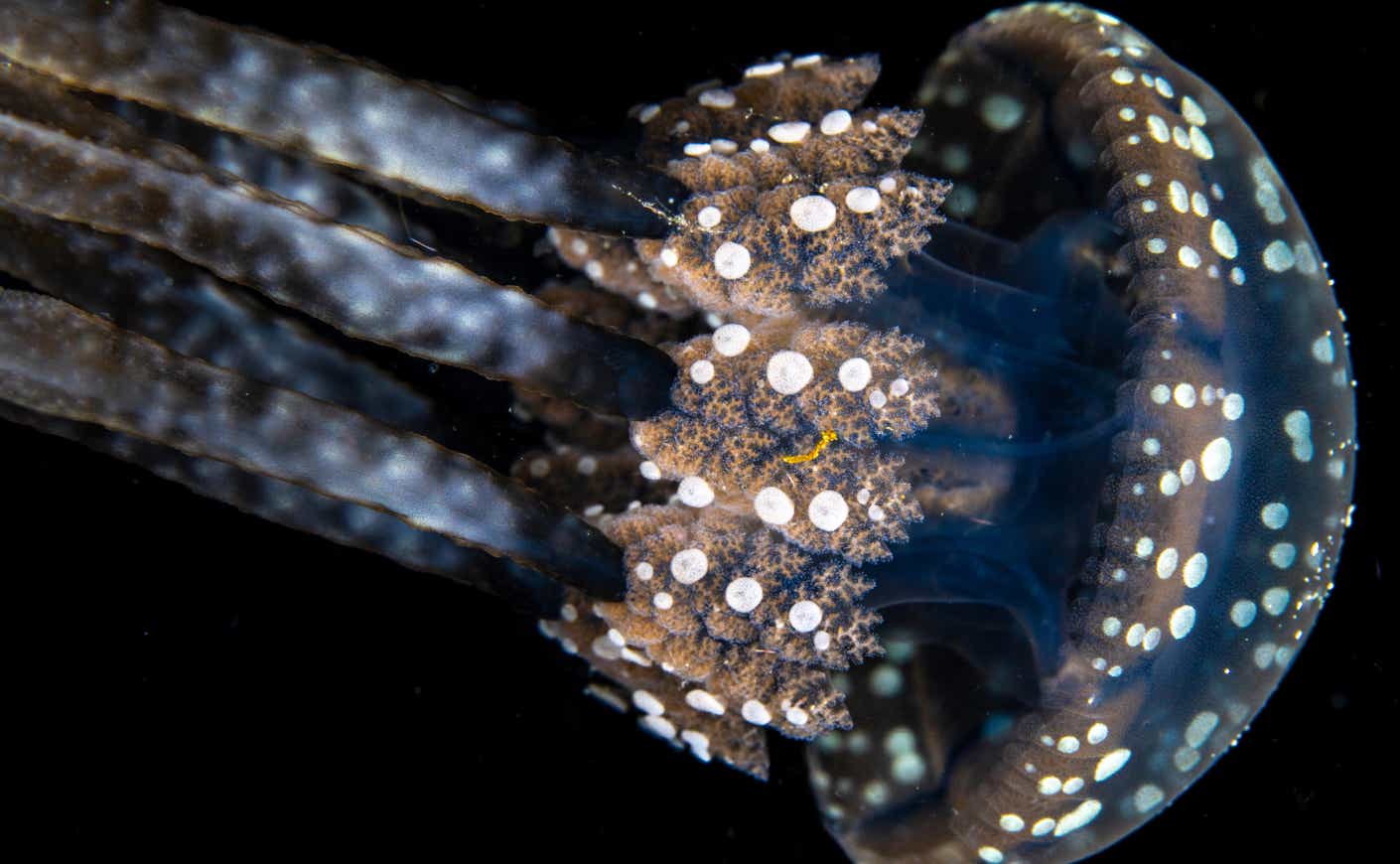

The deep sea is not a lifeless desert. It’s home to ecosystems that play a crucial role in regulating our climate and supporting ocean health. Mining would stir up massive sediment plumes, release stored carbon, and create industrial noise that could disrupt fisheries and whale migrations. For all the promises of powering a green transition, deep-sea mining risks creating a whole new environmental crisis — one we don’t fully understand and may never be able to reverse.

Over breakfast on the first day, I expressed my excitement: “This week we’ll find out whether the ISA allows deep-sea mining or if they’ll finally call for a moratorium.”

Someone laughed and replied, “That’s what they say at every meeting.” It only took until the end of the first day for me to see what they meant.

More than 80 countries support the need for a strong environmental policy before any mining can begin. On the surface, that sounds like progress — and in some ways, it is.

But the reality is more complicated: There’s still very little science on deep-sea ecosystems. Ahead of the UN Ocean Conference earlier this year, the world’s leading deep-sea scientists released a statement that we need around 10 to 15 more years of research to properly inform mining regulations.

Yet fewer than half of the countries pushing for environmental policy were willing to acknowledge that reality and call for a moratorium. Instead, vague commitments became a convenient way to delay mining without taking a definitive political stance.

This is what a lack of political will really looks like: not outright denial or an opposition to science, but hesitation. Governments agree in principle, but hold back on making an official statement unless it’s politically safe to do so.

The ISA has been stuck in this kind of limbo for years now — a slow-motion diplomacy that has, for better or worse, bought the deep sea more time. But that stalling has also driven The Metals Company (TMC), a Canadian mining firm, to threaten to mine unilaterally with the U.S., bypassing the ISA and challenging international law.

In response, some nations proposed rushing weak regulations just to maintain authority. For countries that see mining as inevitable, they’d rather have a flawed framework than none at all. That logic has pulled in even those who might otherwise support environmental precaution.

It was concerning to see some governments so quick to bend to corporate pressure. What kind of precedent would that set for global governance?

And yet, there is hope.

Political will doesn’t shift on its own. SeaLegacy’s social footprint has helped make deep-sea mining a mainstream issue, educating the public and shaping opinion. The work that organizations are doing on the ground at the ISA is making a real impact. New ISA leadership under Leticia Carvalho, an oceanographer who understands the ISA’s duty to protect the environment, has also shifted the focus away from industry and renewed a sense of hope. Together, these efforts are shifting political will, bit by bit. If enough people speak out, a moratorium will eventually become the politically safe option.

Even if TMC follows through on its threat to mine with the U.S., it won’t be without consequences. Mining without global consent carries enormous reputational, legal, and financial risks. It could trigger investor pullout, international condemnation, and logistical nightmares. We can make sure it’s simply not worth the cost.

Despite everything, I left Jamaica feeling positive. Progress might be slow, yet things are moving in the right direction. But we can’t afford complacency. This meeting made clear just how fragile international governance really is. Loopholes and silence are letting corporate interests push the system to its limits.

At the same time, I saw how much influence we still have. Scientists, youth, Indigenous leaders, and civil society are shifting the conversation. The pressure we’re building is working — we have to keep going.

Join us in protecting what should never be plundered in the first place:

Stay informed: Follow @sealegacy & @soalliance on Instagram for updates.

Add your voice: Sign Sustainable Ocean Alliance’s letter to add your name to the global campaign for a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

Call your representatives: Urge them to support a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

Jamie Goncalves is a marine biologist and science communicator focused on ocean conservation and environmental policy. He works at the intersection of science and storytelling, making complex marine issues accessible to the public. Jamie writes for SeaLegacy and covers a wide range of science and conservation topics worldwide. For more updates on his meaningful work, learn more about SeaLegacy, and subscribe to Ripple Effect, Katie Couric Media’s sustainability newsletter.