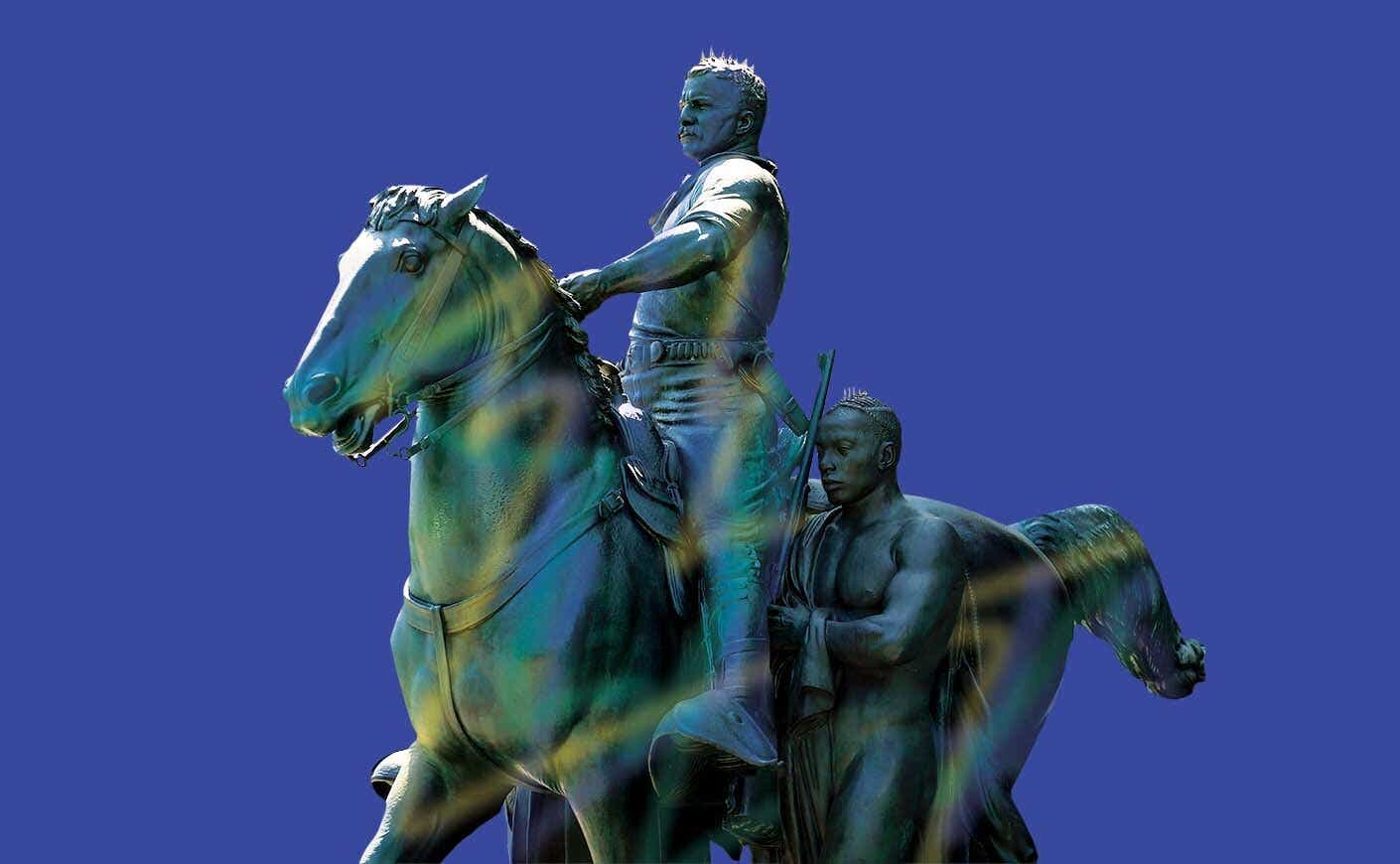

The office of the President and the power it commands has rarely, if ever, come under the kind of scrutiny it has in the past few years. Leaders of the past are being reexamined according to the values we admire and condemn today — from heroism to violence and racism. The characters immortalized in stone and metal during the “statue mania” of days gone by no longer command the reverence they once did, and the glaring bias in favor of the “great” white men of history has never looked so stark as it has in a modern age marked by BLM protests and far-right rallies.

To mark this President’s Day — aka, George Washington’s birthday — KCM spoke to historian and author of Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues That Made History Alex von Tunzelmann for some deeper thoughts on the complicated issue of commemorating these historic figures, and why our approach to remembrance is constantly shifting in response to political and social forces in flux today.

KCM: George Washington’s statue in Portland was targeted in 2020 by protestors who claimed that his slave-owning history made him a symbol of deep-rooted injustice. But George Washington still occupies a largely positive place in the public. Similarly, Winston Churchill’s statue in London was graffitied with the (accurate) statement, “Churchill was racist” in 2020, but there’s still a powerful reverence for him in Britain. Given the often blurry line between racist enough to topple and relevant enough to stay, do you foresee more controversies over “gray area” American figures in the years to come?

Alex von Tunzelmann: Absolutely, yes — I don’t think these arguments are going away on either side of the Atlantic. Churchill and Washington are highly contested because they’re so venerated. This means they get more statues than most other historical figures, and that visibility inevitably leads to more public scrutiny. There’s a whole range of controversies in the U.S. at the moment about how history should be remembered and how it should be taught in schools. These aren’t just about the facts of the past: they are clashes over how we remember, what we celebrate, and how we present to a new generation, all issues of concern in the present.

It’s important to note that pressure isn’t just coming from the left or from Black Lives Matter. There’s also a strong reassertion of white identity politics coming from the far right. Statues of Confederate figures, for instance, have become modern flashpoints because historically, they were rallying points for the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups. So the question around any statue isn’t whether a historical figure is in a “gray area” in terms of their own behavior: It’s what displaying that statue as an object of veneration means today.

Are there other statues of American presidents that you think are likely to become targets for removal in the near future — and if so, which ones?

Controversies about how we remember the past are born out of what we care about in the present. So whatever is causing friction in the present day, people will look at the roots of that issue and how it’s been presented to them.

I think race and colonialism are likely to remain flashpoints for a while, and of course, it follows that there will be more discussion about the Founding Fathers. You may also see specific political reactions driven by controversial figures in the present day. Donald Trump has often made a point of praising Andrew Jackson — and if he identifies strongly with Jackson, then we may see a response to that both from his supporters and his opponents.

Are there any statues of American presidents that you feel should get taken down?

It’s not my place to say! I believe strongly that each community should make its own decisions about its built environment. If statues or monuments are a part of that, it’s up to the community to decide what represents them or doesn’t.

One of the issues with statues as a medium is that they tend to reinforce a male bias in our commemoration of history — because most famous historical figures are white men. Might more statues of women be a potential means of redressing that balance? What might some risks be?

You’re absolutely right, most statues are of white men. There have been lots of campaigns to put up more statues of women or people of color. These are well-meant, but I feel they really compound the problem.

Many of the current statues we see come from the late 19th to early 20th century “statue mania” — a period when hundreds of statues were put up across North America, Europe, and colonies. This “statue mania” was inspired by the Great Man theory of history — the idea that history is created by singular, powerful men who drive change and progress by themselves.

The Great Man theory is inherently patriarchal and strongly linked with the history of colonialism and white supremacy. So, to my mind, putting up more statues of women and people of color is a form of tokenism, because it doesn’t challenge the Great Man theory. It reinforces and validates this regressive idea that history is all about singular individuals rather than being a group effort. There are plenty of monuments and memorials that don’t focus on individual glory — think, for instance, of war memorials, which can be extremely moving. If we want truly inclusive monuments, we can do much better than individualistic statues.

You wrote in Fallen Idols that “man of his time”-style arguments shouldn’t hold because times “do not have opinions.” Essentially, you seem to say that “it was the done thing” isn’t a sufficient excuse for racism and imperialism. To what standard should we hold historical figures, if any?

My problem with the “man of his time” argument is that it assumes that there was one standard opinion at any one time. That’s never been the case. I find it extraordinary when people make sweeping statements like “everyone supported slavery back then.” We know that many enslaved people did not support slavery, as they were constantly in rebellion. We also know that many white people found it abhorrent — religious groups like the Quakers were vocally in opposition from the start. So to say “everyone supported it” is to erase a huge number of voices, including enslaved people themselves, who really ought to be at the center of this debate.

The question of what standard we should hold historical figures to needs to be broken down because two different discussions are going on here. One is when historians look at historical figures. The way historians approach the past isn’t to judge figures as “good” or “bad.” The questions historians ask are usually “how” and “why”: we’re seeking a complex, nuanced understanding of the past in its context.

But that historical process is completely separate from the discussion about statues. Statues aren’t history — they’re propaganda, idols raised for veneration. They don’t present complex or nuanced arguments about the past. They’re about who we celebrate and what values we promote today. The person who sets the standard unbelievably high for any historical figure is the person who put the statue up in the first place: They raised a human being to the status of a superhero or demigod. Of course, people will dispute that, and in a democracy, they should.

You make the argument that statues themselves are the problem — because they are ”didactic, haughty and uninvolving” — and argue that books, museums, and festivals are a more participatory way to bring history to life. These media require a conscious will to engage on the part of the public, which may not always be present. How can this gap be bridged?

I don’t think you should underestimate the public! The main barriers to engagement are time and money. So the way to bridge the gap in engaging the public is to make it free and easy for everyone to access museums, events, and books via libraries. That means these things need to be well-funded, well-run, and accessible to all, and that working people need to have enough leisure time to be able to pursue their interests.

Is the relative simplicity of statues as a medium necessarily a bad thing? Do they have any redeeming features as mementos of the past?

There’s a difference between honorific portrait statuary and artistic sculpture — of course, sculpture is one of the world’s great art forms. But even if we’re just thinking about honorific portrait statues, they can be beautiful, witty, or charming. Statues of celebrities or animals are often more popular than those of politicians — think of Balto the Husky in Central Park, New York City, or Rocky at the top of the steps up to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Some sculptors have deliberately subverted the form of statues, such as Corporate Head, a lifesize bronze statue of a businessman with his head stuck in an office block in Los Angeles. If a statue enriches its environment and is liked by the community who live with it, that’s wonderful.