More and more classified documents are turning up in places they shouldn’t be, raising fears about whether the U.S.’s national security has been put at risk.

First, there was the August 2022 seizure of hundreds of confidential documents at Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence in Florida, and then, in January 2023, similar files were found in President Biden’s private home and office in Wilmington, Delaware. Just when you thought the revelations had come to a head, a lawyer for former Vice President Mike Pence discovered a trove of White House records at his home in Indiana. And yet, this could be just the beginning.

“If I were a former vice president, president, or senior White House official, I'd be searching through all my boxes because a good number of them probably have classified marked records,” says prominent national security lawyer Mark Zaid.

While recent coverage may make it sound like a rarity, what’s known in intelligence circles as “classified spillage” is relatively common, according to former intel and national security officials who specialize in cases involving delicate government information.

Former CIA Chief of Staff Larry Pfeiffer says he remembers instances where similar confidential files were inadvertently found at presidential libraries (though he didn’t specify which presidents they were). Luckily, he said, researchers stumbled across them and flagged them to the proper authorities. The reality is this kind of thing happens several times a year, underscoring some room for improvement when it comes to safeguarding classified presidential documents.

“I never liked the idea that any classified material is sitting somewhere inappropriate — it puts the material at risk and the sources at risk, so it's very dangerous,” Pfeiffer tells Katie Couric Media. “Experts in record access management, storage, and classification should be commissioned.”

Naturally, this begs some questions: What are classified documents, exactly, and does the government have any systems in place to protect confidential data? You may be not-so-pleasantly surprised.

What does it mean for a document to be classified?

We’ve been hearing the term “classified” thrown around a lot lately, but what does it actually indicate? The word generally applies to any documents that the government considers to be sensitive — and to be privy to them, one must pass the proper background checks and be granted the necessary security clearances.

As far as the types of classified documents go, these can really run the gamut, ranging from paper documents and emails to databases and hard drives. They’re also usually broken down into three main levels: First, there’s “confidential,” which is the lowest category, then there’s “secret,” followed by “top secret.”

Classified documents are treated delicately in the White House, but they often get intermingled with unclassified material. A national security official who worked in the Obama and Trump administrations (and spoke to us on the condition of anonymity, due to an ongoing investigation), tells us that unclassified material is allowed on classified networks, but not the other way around. Here's an extreme example: You could find something as innocent as an email concerning two officials' lunch plans alongside the most heavily guarded data, like details of our nation’s nuclear weaponry. As you might imagine, these mix-ups can be tough to track down — especially at the end of an administration’s term.

The laws around classified documents

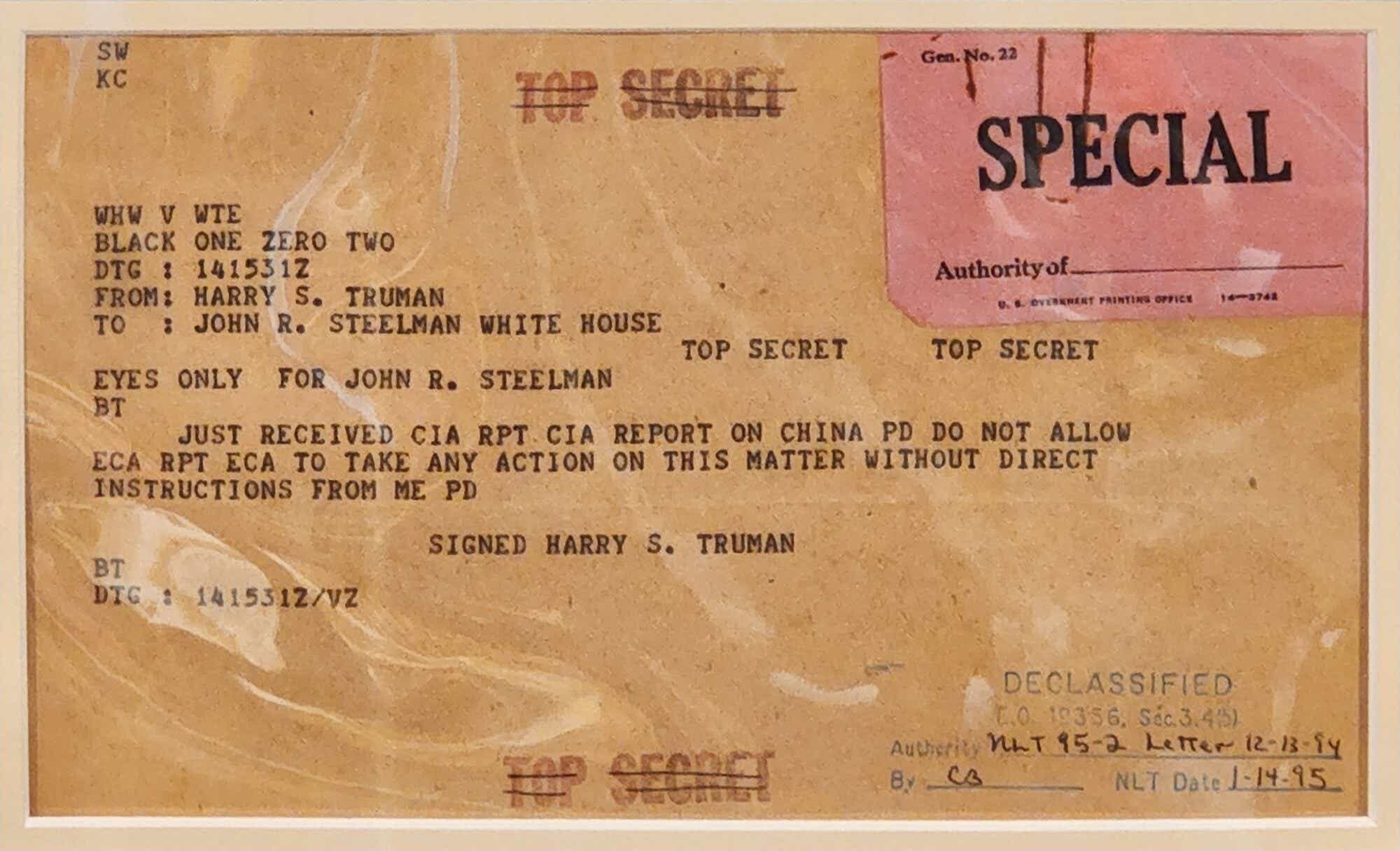

Up until a few decades ago, there was nothing really prohibiting presidents, vice presidents, or their staff from taking home classified records — and they did it all the time, according to Zaid. (Believe it or not, Zaid currently owns a top-secret telegram from President Truman to his assistant John R. Steelman that was found by his family years later and returned to the National Archives before it was declassified.)

“I would not be surprised at all if every living president or vice-president and possibly senior staff mistakenly possess documents in their attics, garages, and closets that are still marked classified and they don't even know it,” Zaid tells Katie Couric Media.

Today, we have the Presidential Records Act, which governs what White House staff can and cannot take home. The measure also changes the legal ownership of the official records of the President from private to public. But it took President Nixon nearly destroying records related to his tumultuous presidency before the legislation was eventually enacted by lawmakers in 1978, and it didn’t take effect until 1981.

Aside from the Presidential Records Act, there are several federal laws, including the Espionage Act, that makes it illegal to remove, disclose, or destroy classified information. If White House officials — including the president —commit any of these missteps, then they could face up to 10 years in prison and hefty fines, but the decision to prosecute isn’t always so clear cut.

What are the punishments for illegally possessing classified material?

Whether or not an official faces criminal charges depends on a number of factors. One of them is the nature of the classified documents — i.e., what they contained — and why they were removed, though Zaid tells us that “there doesn't technically need to be intent to find liability.”

A larger pile of these sensitive materials could also make for a more compelling case for prosecutors, which could spell trouble for Trump. While a small number of documents have been found at Pence and Biden’s homes, roughly 300 documents with classification markings — including some at the top secret level — were recovered from Trump since he left office in 2021. Another big difference is he refused to give the documents back after it was made clear to him that he had been holding on to them illegally.

“If Trump had returned all of the documents and cooperated fully with the National Archives in the months after Biden was inaugurated, I'm confident nothing would've ever happened to him from a legal standpoint,” Zaid tells Katie Couric Media.

The protocol for a departing president

Ahead of an outgoing administration’s departure, all documents related to the commander-in-chief are expected to be sorted, cataloged, and handed over to the National Archives in Washington for processing to determine whether they can be made public. The handoff itself generally happens on Inauguration Day — while the new president is being sworn in, vans come in to transport these documents to the Archives, which will determine which files should be made public and which ones should be kept under wraps.

But the efficiency of handing over these presidential documents really depends on how “how planful the individual administration was or wasn't,” according to the former Obama and Trump security official.

In many cases, there’s a last-minute frenzy because the administration needs these documents until the very end of the term. The downside is this leaves staffers just a few weeks — or less — to pack them up. During this time, potentially hundreds of White House employees must also get their own things together and separate their personal documents (both physical and electronic) from those that need to go to archivists.

“Records management and things of that nature kind of fall to lower priority,” says Pfeiffer. “So I'm not at all surprised that towards the end of an administration, they're scrambling to get stuff done from a policy perspective.”

“A gentleman’s agreement”

One major flaw with the current records system is that the Presidential Records Act lacks teeth when it comes to enforcement, thanks to the traditional authorities granted to the executive branch of government. This, in effect, has created a “gentleman’s agreement” between the White House and National Archives, according to former Obama and Trump officials.

“There's no third party checking to make sure that the administration is cooperating with the archives because it's the executive office of the president — there's no higher authority — and it’s really complicated legally,” our source tells us.

Experts say the solution could be amending the Presidential Records Act to ensure more compliance from the White House and modifying some of the implementation policies. But our source explains that for the most part, the law already works as it should — presidents and past officials have largely abided with the obligation to return documents marked as classified, with Trump being a major exception.

Still, Zaid doesn’t think this is enough of a reason to fundamentally change the current bill, pointing out that Biden and Pence both followed the proper steps in alerting federal officials.

Room for improvement

Thousands of White House officials touch classified records on any given day, so the analysts we spoke to say the misplacement of sensitive information is unavoidable on some level.

“Human beings by their very nature make mistakes, so clearly in some rush to pack up and move out stuff from the end of an administration, classified documents can get intermingled in with unclassified and get stored in inappropriate locations that aren't secure,” says Pfeiffer.

But there are some steps that White House officials can take when it comes to better safeguarding sensitive material. In addition to revising the laws, Pfeiffer adds that it would be useful to improve the training around the handling of government documents and then a greater reliance on electronic record keeping.

“Greater reliance on electronic records — perhaps some additional logging and tracking — could be done to at least identify what documents have not been found at the end,” he tells us.

Whether or not there will be any legislative action remains to be seen, but what we do know is that the recent revelations around Trump, Biden, and now Pence’s documents are likely just the tip of the iceberg in what could be a much bigger problem.

For more on the complicated legal concerns around classified material, check out Katie's interview with legal expert Neal Katyal: