We usually don’t think about food and nutrition as political issues, but they are. Politics affect what’s sold, how it’s marketed and to whom, and where it’s accessible and at what cost. We can’t separate societal norms and dominant culture from how each of us accesses food and thinks about it in relation to ourselves.

Similar to your beliefs, heritage, socioeconomic status, and so on, what we eat has an impact on how we measure ourselves, whether we’re aware of it or not. And it's become clear that how we identify can affect how we vote.

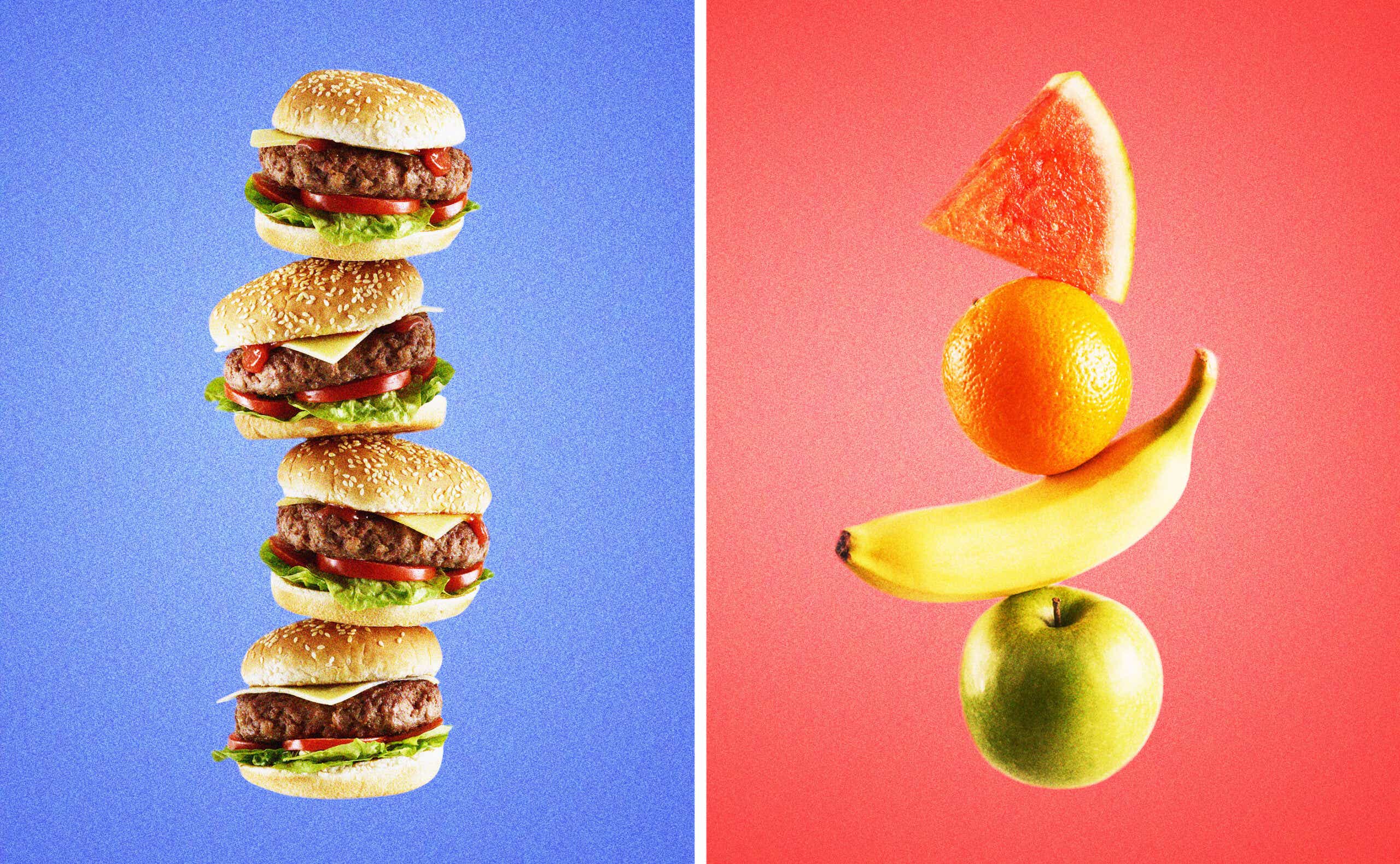

Eating is essential for life but not everyone is afforded the same options. There’s an implicit understanding that fresh and organic superfoods are at the top of the food hierarchy, while canned or frozen foods are substandard options utilized by those who we’re conditioned to believe don’t care about their health. Wellness marketing has done an excellent job of categorizing healthy food versus junk food: Google “healthy food,” and you’ll be flooded with images of fresh fruits, vegetables, seafood, chicken, and brown rice. Yes, all of this is healthy, but it only represents one version of health, and that version doesn’t consider socioeconomic, historical, cultural, or identity factors. The most commonly referenced version of “healthy food” is not representative of the cultures and identities that make up our population. It’s no coincidence that lack of diversity is an increasingly common complaint across our entire democracy — people who identify as a part of minority groups struggle to feel seen and represented in Western governments.

The first step to combatting the inequalities in eating is to recognize why they exist.

Gender Identity

Gender identity influences how a person interacts with food and wellness as well as how the person is viewed in terms of health. Dominant norms, societal expectations, and stereotypes surrounding body image and food consumption have a significant and often unspoken impact on eating patterns. Women are often subjected to unrealistic beauty standards, which can lead to restrictive eating habits and disordered relationships with food. Black women experience the double burden of gender bias compounded with racism, and it starts at a young age. Research tells us that Black teens are 50 percent more likely to present with a binge eating disorder. The prevalence of binge eating disorder among Black women is 5 percent — it’s 2.5 percent among white women. Additionally, the pathway to this eating disorder for Black women is linked to systemic inequities, stress, and trauma.

People who identify as men may feel pressure to abide by dominant and traditional norms around masculinity. The National Eating Disorder Association notes that one in three people with an eating disorder identify as male. Social media encourages high-protein diets paired with heavy gym sessions as the path to achieving the male ideal. Society praises excessive exercise in men — in fact, it's encouraged and thought to be a part of health-forward behavior when it could be dangerous in some cases.

Race

What you think of as healthy is also influenced by dominant norms. Historically, Anglo-American and Anglo-European foodways have been lauded as the patterns to adhere to in order to achieve optimal health. Mainstream articles have warned readers about the perils of consuming unhealthy Chinese food or calorie-laden Mexican food while steering them toward steamed vegetables, boiled chicken, and baked potatoes. Thankfully, new research exploring Latin American, Asian, and African heritage diets has proposed that these patterns of eating can be just as nutritious as the widely researched Anglo-European diets. These previous recommendations have been steeped in xenophobia and bias.

Socioeconomic Status

Current federal and state governmental policies and regulations have a profound impact on the accessibility and affordability of foods. Historically marginalized and lower-income communities have typically had an abundance of access to liquor stores, smoke shops, low-cost fast food chains, and dollar stores. Socioeconomic disparities often lead to unequal access to healthy and nutritious foods, contributing to disparities in health outcomes. Well-funded neighborhoods with higher median incomes boast significant choices concerning safe and nutrient-dense food options in comparison to poorer neighborhoods. Additionally, the food industry heavily influences what choices are available through intentional marketing and lobbying efforts that vary significantly based on the community in which someone resides.

Looking deeper at the politics of eating affords us the opportunity to highlight the complex intersectionality of gender, race, and socioeconomics as it relates to nutrition and food. It’s pertinent that we open our eyes to the structural factors that shape our interactions and understanding of the foodscape.

Maya Feller, MS, RD, CDN of Brooklyn-based Maya Feller Nutrition is a registered dietitian nutritionist and author of Eating from Our Roots: 80+ Healthy Home-Cooked Favorites from Cultures Around the World (goop Press), and Co-Host of Well, Now Podcast, Slate’s new wellness podcast.