Governor Tim Walz has been justly hailed for calling Donald Trump “weird,” a sly, brilliant takedown which undercuts rejoinders and renders them absurd. What can he or others who emulate him say? “I’m not weird,” or “You’re weird, too” both seem like lackluster rejoinders.

Kamala Harris has chosen Walz as her running mate, in part it seems, because of this comment, and his words are everywhere on the internet.

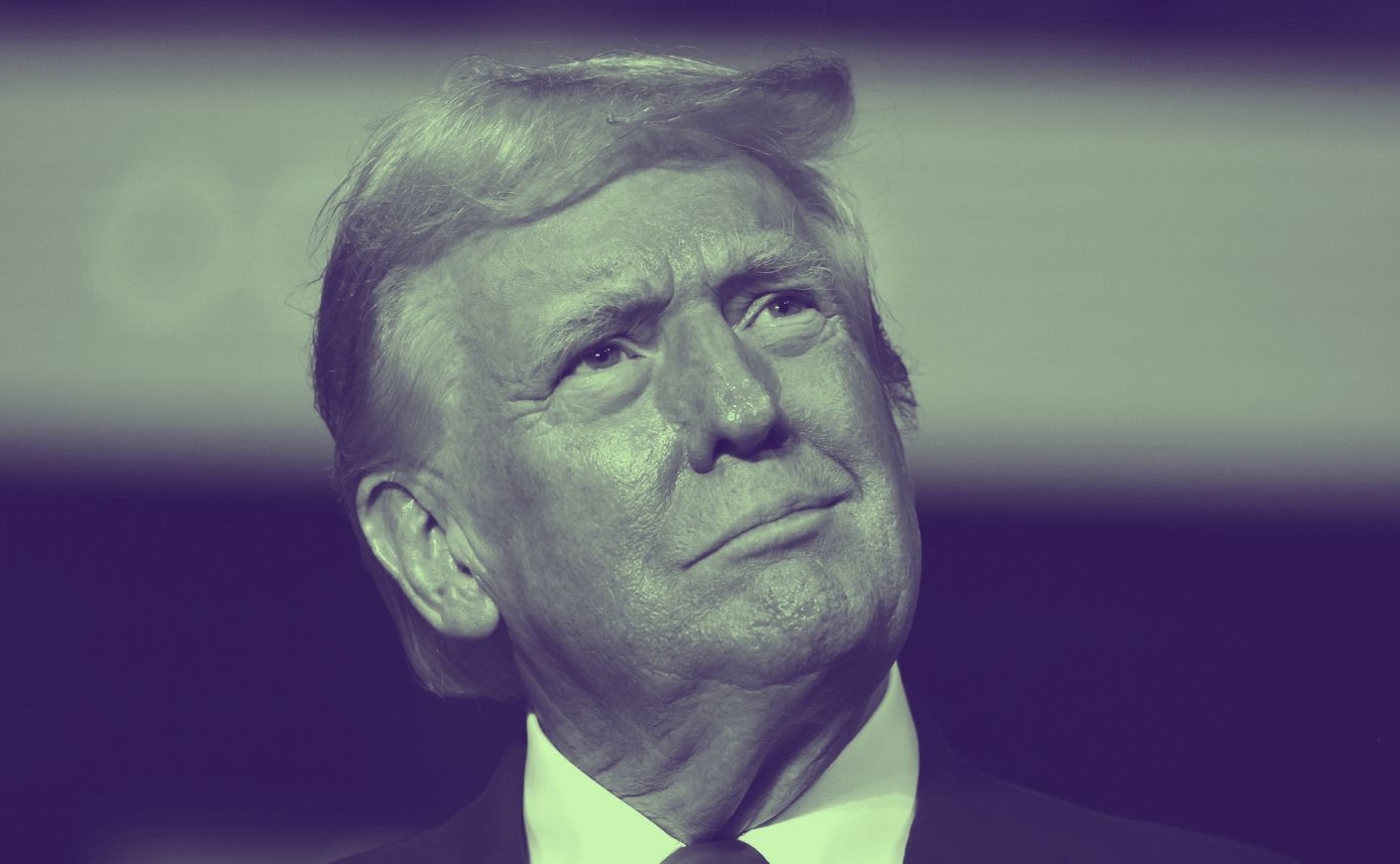

And, indeed, Trump is unusual, different, and strange — weird — in a wide variety of unpleasant and obvious ways, from his compulsive repetition of lies and schoolyard taunts, to his sad orange combover.

However, to me, a man who grew up in New York City at the same time as Donald Trump and whose father moved in the same world of real estate and hotel deals as Fred Trump, his son, Donald, is not all that unusual or different. Trump’s signature name-calling, his racial and misogynist dismissal of opponents and indeed anyone who dares to disagree with or question him, his desperate one upmanship — they all echo language and attitudes that I heard while growing up. From older white men in 3rd Avenue bars near my family’s Yorkville apartment to my father’s locker room “debates” or park-bench conversations with “experts“ eager to share their worldly wisdom with a curious boy.

These were, I recognized even as a teenager, the words and opinions of men who seemed to derive satisfaction from distinguishing themselves from others whom they regarded as inferior, men who were inviting me to share a perspective that was self-congratulatory and derogatory toward others. The “n word” was frequently used, but so too, depending on the ethnic status of the speaker, was every imaginable demeaning epithet for Hispanics, Asians, Eastern Europeans, Irish, and Jews. People I suspected, even then, that the speakers may have seen as threats, and who reminded them of their own humble origins and vulnerabilities.

The disparagement of women was a bit harder for a teenage boy to understand. How could a pot-bellied barfly, dribbling drink and dip onto his shirtfront, call a woman with slightly smeared lipstick “a slob”? Years later, as a young psychiatrist, it seemed clear to me that in insulting women, these guys were likely denying and projecting their own very obvious shortcomings onto the women, and perhaps taking revenge on a gender whose indifference and power they feared.

This climate of insecurity and insult, of denial and projection, was a toxic brew which I came to understand was liberally dispensed to their children. Trump’s father, Fred, was paradigmatic. He didn’t only preach a conventional striver’s doctrine of winners and losers — for Fred Trump, the distinction was between “killers” and losers. He and his son Donald were always right and were never to admit that they were wrong. Reading the accounts of the Trump family, including the former President, it seems clear that those who disagreed with them were not only regarded as opponents, but as losers who deserved whatever they got, including death.

November 06, 1987. (Photo by Dennis Caruso/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

The infamous lawyer, Roy Cohn, Joe McCarthy’s attack dog and Trump’s mentor, (and another figure who shadowed our childhood) further poisoned the brew. Cohn exhorted his clients to deny, deny, and “always hit back.”

Which leads me to the ways in which Donald Trump is, indeed, truly “weird," in the more noxious and ominous, Old English sense of the word: manipulative, malevolent, threatening, and also uncannily odd. This is the weirdness of the witches in Macbeth, who in the opening scenes of the play, predict disasters they may well be precipitating. It is the weirdness on which Trump the politician prides himself, in which he invites his followers to participate.

We hear this weirdness in Trump’s transparently envious observation about the late Senator John McCain: “He’s not a war hero... I like people who weren’t captured.” This is what makes our skin crawl when, echoing Hitler whom he claims not to have read, Donald Trump calls immigrants “animals” and warns that they are “very contagious” and “poisoning” the blood of our nation.

These are the echoes of dark weirdness that we also need to recognize in Trump’s grim attempts at humor — his musings about the appeal of the cannibal Hannibal Lecter, and his soliloquy about the difficult choice between death by electric boat and shark attack.

So, yes, it is good to use “weird” as a way to undermine and detoxify Trump’s self-importance and that of his vice presidential choice and their acolytes. It signifies amused disdain and a refusal to participate in the grimy verbal grappling on which they thrive. But it’s even more important to understand Donald Trump’s true weirdness, his malevolent intent and his commitment to making his vision of division and destruction a reality — a very real threat to us all.

James S. Gordon, MD, a psychiatrist, is the author of Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing. He has worked for more than 30 years with population-wide psychological trauma overseas and in the U.S. and was the chair under Presidents Clinton and George W. Bush of The White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy.