Last year, we joined forces with Katie Couric to make An American Bombing: The Road to April 19th, a documentary film that premiered on HBO in April 2024 (and is now streaming on Max). It was created to shed light on one of the most devastating tragedies in recent history: when, on April 19, 1995, ex-Army soldier Timothy McVeigh took the lives of 168 people (19 of them children) by bombing the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. Today is the 30th anniversary of this deeply disturbing tragedy.

The film was Katie’s idea originally: She had approached HBO about revisiting the event. As the TODAY show co-anchor in 1995, she was on the ground in Oklahoma City soon after the explosion, and she wondered how the surviving victims and family members were doing, so many decades later.

As documentary filmmakers, we have a longtime relationship with HBO, having made several films for them over the years. We’d actually made one about the bombing for Bill Moyers in 1996 — a special for the TODAY show — that focused on some of the people most deeply affected by the tragedy. HBO introduced us to Katie and we set off together to tell the story.

We started by contacting the people who’d been in our earlier film; we had stayed in touch with some of them over the years and were moved to see how they had turned their grief into life-affirming missions.

Bud Welch lost his daughter, Julie, in the bombing; he admitted to having wished someone would kill McVeigh. But over time, he remembered his daughter was opposed to the death penalty, and that the best way to honor her memory was to fight against capital punishment. He eventually befriended McVeigh’s father, Bill, and went on to become a global human rights activist.

Marsha Kimble lost her daughter, Frankie, in the bombing. In the wake of that loss, she organized a group called Families and Survivors United that got federal legislation passed allowing survivors and family members of victims to watch the trial on closed-circuit TV. (Additionally, if they chose to attend the trial, they could testify during the sentencing phase.) This led to Marsha becoming a national victims’-rights advocate — one who came to NYC after 9/11 to work with grieving survivors and family members of victims.

Kathy Sanders lost her two grandsons, Chase and Colton, in the bombing. A few weeks later, she and her husband Glenn hosted a dinner for the families who’d lost their children in the Murrah Building’s daycare center. One of the mothers asked if anyone else had seen the bomb squad at the building earlier on the morning of April 19. That question started Kathy on her own journey as a citizen investigator: She realized she didn’t know the whole story and was determined to find out the truth. (The result of her research into possible cover-ups and theories was a book called Shadows of Conspiracy: The Untold Story of the Oklahoma City Bombing.)

Nancy Shaw survived the blast that killed so many of her co-workers in the Murrah building’s Social Security office, and we were relieved to find her well. She had continued working for Social Security after the office moved to another location and had retired a few years earlier. Remembering that explosion in April, she says in the film, “It felt to me like my skin was burning off, and it was a wind so powerful that it felt like it pinned back my hair.” (Shaw said she thought she saw McVeigh in the elevator in the months prior to the bombing, but wonders if that was a false memory — though the head of the daycare center also reported seeing him.)

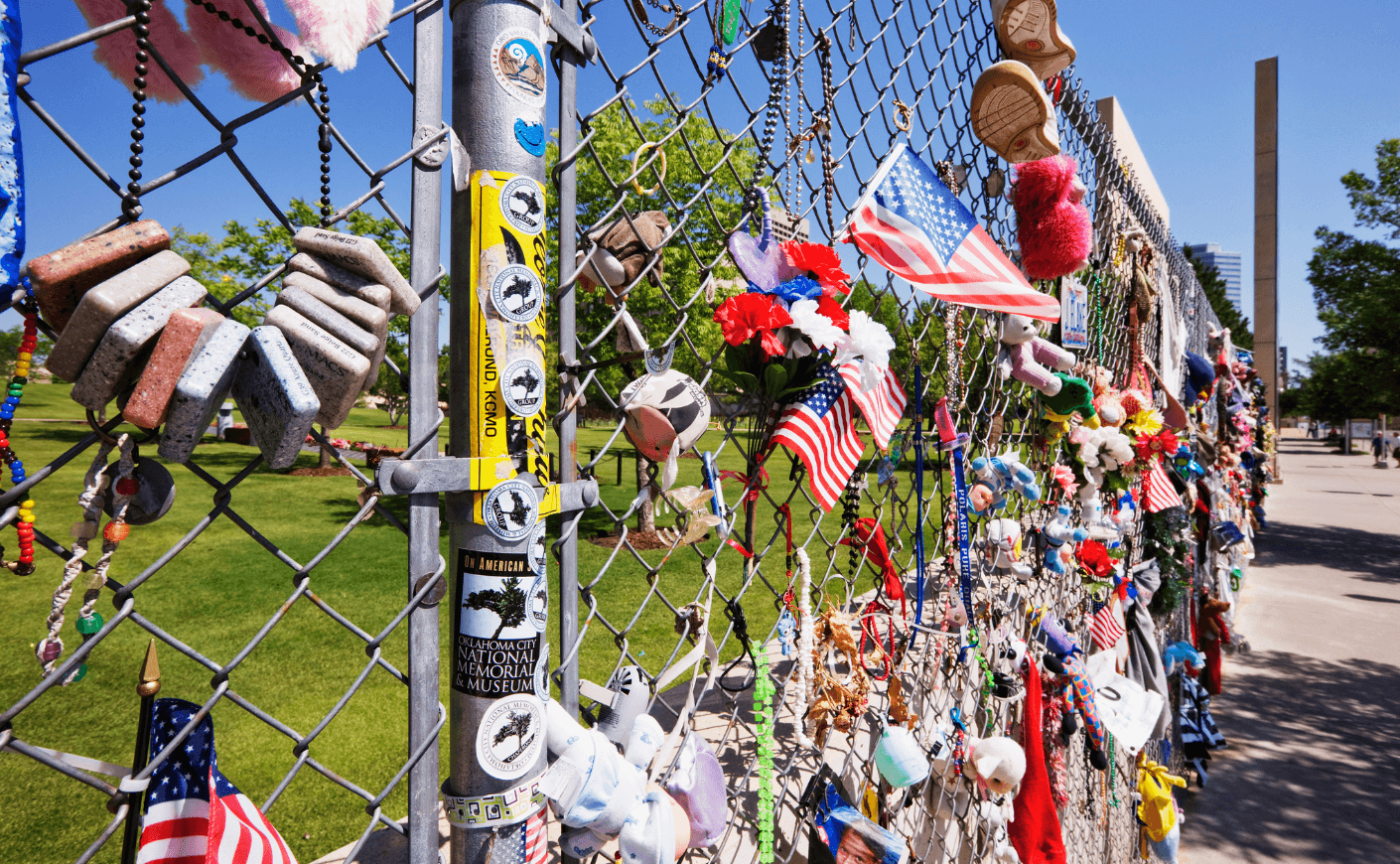

LaDonna Battle-Leverett lost her parents, Calvin and Peola Battle, in the Murrah building — the couple was at the Social Security office for a 9 a.m. appointment when the bomb exploded. The Battles’ four daughters had to wait 14 days for their parents to be found in the rubble. She was shocked when she eventually saw McVeigh in person, in court: “You're looking for the monster and you finally get that day to see him, and you're thinking like, Wait a minute, is this him? He looked like anyone’s kid. Just your normal average Joe.” She remains actively involved in Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum events, speaking about her experience to keep alive the memory of what happened there.

We found that the memory did indeed need to be kept alive: We were surprised during our research for An American Bombing to learn that few people under the age of 35, outside of Oklahoma, had even heard of the tragedy. Somehow the story had been erased. So we had to figure out how to recount the most important elements of the case to make it understandable to viewers, without overwhelming the film. We also realized we had to go back in time to show what informed and motivated the perpetrators, an effort that took us back to the early 1980s. There were many narrative threads to interweave, and a massive amount of information to collect and pore over.

In making the documentary, we searched for “characters” who had experienced the events surrounding the bombing from various firsthand perspectives to keep the storytelling dynamic and engaging, including FBI agents, investigative journalists, attorneys on both the defense and prosecution sides, and Kerry Noble, a former member of an extremist religious group, to give us an insider’s view.

Noble enabled us to include the most provocative information — that the Murrah building had been targeted by the members of his group in 1983. One of those members, Richard Snell, was executed on April 19, 1995. for murder — the same day as the OKC bombing — prompting many to question whether the bombing had been carried out to honor him in some way. This also raised the possibility that McVeigh was part of a larger movement that hid its connections in terrorist cells.

Katie introduced us to Bill Clinton, who was president at the time of the bombing, but also knew the landscape of anti-government groups from his days as governor of Arkansas. He had rarely spoken on camera about his experience with Noble’s group — The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord (CSA) — which was active in Arkansas during Clinton’s term as governor; he had amazing recall and intimate knowledge about their activities. We were able to pair his retelling with the actual footage of the terrorist compound, matching his words exactly to the images of their camp and bunkers. When he heard about the bombing of the Murrah building on April 19, 1995, his mind went back immediately to the CSA. While others were suspecting Middle Eastern terrorists, Clinton said, “My life and experience told me that there was a very good chance that this was a homegrown plot.”

As President Clinton did, it’s important to understand the Oklahoma City bombing in the greater historical context. In the early 1980s, an anti-government “Patriot Movement” brought together various right-wing extremists who declared war on the U.S. government. Some in that movement inspired, sustained, and even celebrated McVeigh’s act of terror. There were also larger social, economic, and political forces at work that shaped the landscape, making it fertile ground for extremist violence.

As the threat of political violence rises yet again, it’s essential to understand the factors and ideas that led us where we are today. As LaDonna Battle told us, “They covered up the 1921 Tulsa race massacre — we still don't get it. If you cover [something] up, it doesn't get better, it gets worse. We need to continue telling the children this story.”

Marc Levin and Daphne Pinkerson are award-winning filmmakers based in New York City — you can find the latest on their studio Blowback Productions on X and Instagram.