For many Americans, the events of January 6, 2021 may seem like a distant unpleasant memory: an angry mob storming the United States Capitol while Congress was confirming Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 U.S. presidential election over Donald Trump. To some, it was a one-time event that ended when police cleared the Capitol of rioters and Congress was able to complete its task of confirming Biden’s victory. After four years of intense drama surrounding the Trump presidency, many understandably wanted to move on with their lives — to think less about politics and that day in particular.

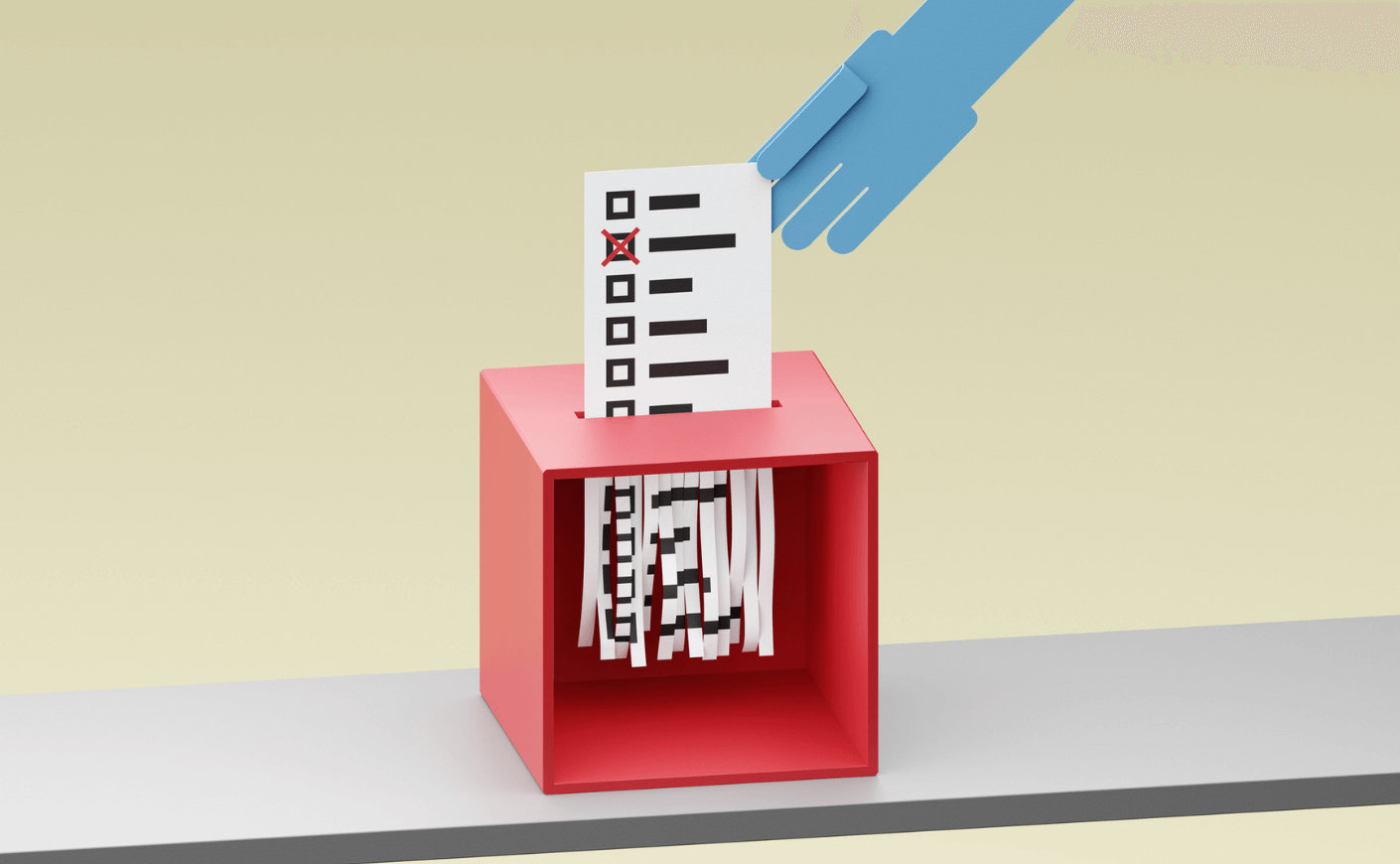

Unfortunately, those events — and Trump’s false claims of a stolen election — have reverberated in political circles around the country, leading to new laws making it harder to vote and, even more ominously, increasing the chances of an actual stolen election in 2024. The window to secure American elections in 2024 is quickly closing.

To start with a key fact: The 2020 election was fairly run (under the difficult conditions of a pandemic) and there's no reliable evidence that any state experienced fraud or irregularities on a scale that could’ve affected election outcomes. That’s the consensus of all reliable election experts, including most recently a key group of leading conservative legal experts. Anyone who tells you otherwise is lying for political or financial reasons, or has been tricked themselves.

But Donald Trump has seen it in his political, financial, and psychological interests to perpetuate the “Big Lie” of a stolen 2020 election. And his message has reverberated: A September 2021 CNN poll found that 59 percent of Republicans said that believing Trump’s stolen election claims was an important part of what it means to be a Republican.

Faced with pressure from Trump from above and the Republican base from below, many Republican state legislators have pushed for new election laws that make it harder for people to register and to vote, all in the name of preventing very rare election fraud. Not all of these laws actually make voting harder, but at the very least they require voters to go through additional, unnecessary hurdles to be able to vote. What’s more, according to recent research by News from the States, “Since the 2020 election, 26 states have enacted, expanded, or increased the severity of 120 election-related criminal penalties... In Oklahoma, for example, voters who apply to receive a blind-accessible ballot electronically but are not blind are now committing a felony. And in Texas, it’s a felony for an election official to solicit the submission of a mail ballot application by a person who did not request one.”

Trump and his allies engaged in an elaborate and multifaceted attempt to have Trump declared the winner of the election, even though he lost. And it could happen again.

As worrisome as it is to make registration or voting harder for eligible voters for no good reason, an even greater concern is the risk of what political scientists call “election subversion,” or stolen elections. Investigations by journalists and by the special House of Representatives committee looking into the events after the 2020 election leading to the January 6 insurrection show that Trump and his allies engaged in an elaborate and multifaceted attempt to have Trump declared the winner of the election, even though he lost. And it could happen again.

In 2020, for example, Trump and his allies made a concerted effort to have election officials such as Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger “find” 11,780 more votes for Trump so that Trump could be declared the winner of Georgia’s electoral college votes — Raffensperger courageously refused. Trump also considered firing his Attorney General, Jeffrey Rosen, and replacing him with a lower Department of Justice official, Jeffrey Clark, who was prepared to have the DOJ declare that there was fraud in elections across the country. This could’ve led state legislatures to try to change state electoral college votes and get Congress to deadlock, ultimately leading to a potential Trump victory.

What stood in the way of Trump’s attempts to subvert the 2020 elections? A group of Republican and other elected and election officials who did the right thing: Raffensperger who refused to go along with Trump’s scheme, the Trump-appointed judges who ruled against him in his frivolous lawsuits, and the Department of Justice officials who threatened to resign if Trump had Clark send out the letter falsely claiming fraud.

The fear is that what failed in 2020 could work in 2024, as some of the heroes of the 2020 elections are replaced by election deniers. In Pennsylvania, for example, the Republican gubernatorial nominee, Doug Mastriano, said that he would not have certified the election for Biden in 2020. If Mastriano is governor in 2024, would he affirm a Biden (or other Democrat’s) victory if Trump (or another Republican) lost the state? If he doesn’t, would possible Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy side with the voters of Pennsylvania, or with a governor who could falsely yell fraud and seek to change the election results?

The United States presidential election process is uniquely open to election subversion because there are so many steps between the time people vote for President, and the time Congress confirms the electoral college votes. Many of those steps require people to act in good faith in declaring winners. Unfortunately, we can no longer count on good faith across the board.

Congress has a chance to act now, and pass a law that would clarify some of the rules for figuring out who has won a presidential election. It would also provide more protection for election workers and take other steps to make election subversion less likely. A bipartisan group of Senators is reportedly close to a deal on such legislation, which will become much harder to pass after the midterm elections if Republicans take back control of the House or Senate.

As much as we may want to forget the unpleasantness of January 6, 2021, we do so at our peril. Now is the time to act, so we don’t have another election crisis come 2024.

Richard L. Hasen is professor of law at UCLA School of Law and Director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project.