A version of this originally appeared on Jonathan Alter’s substack Old Goats, which you can subscribe to here.

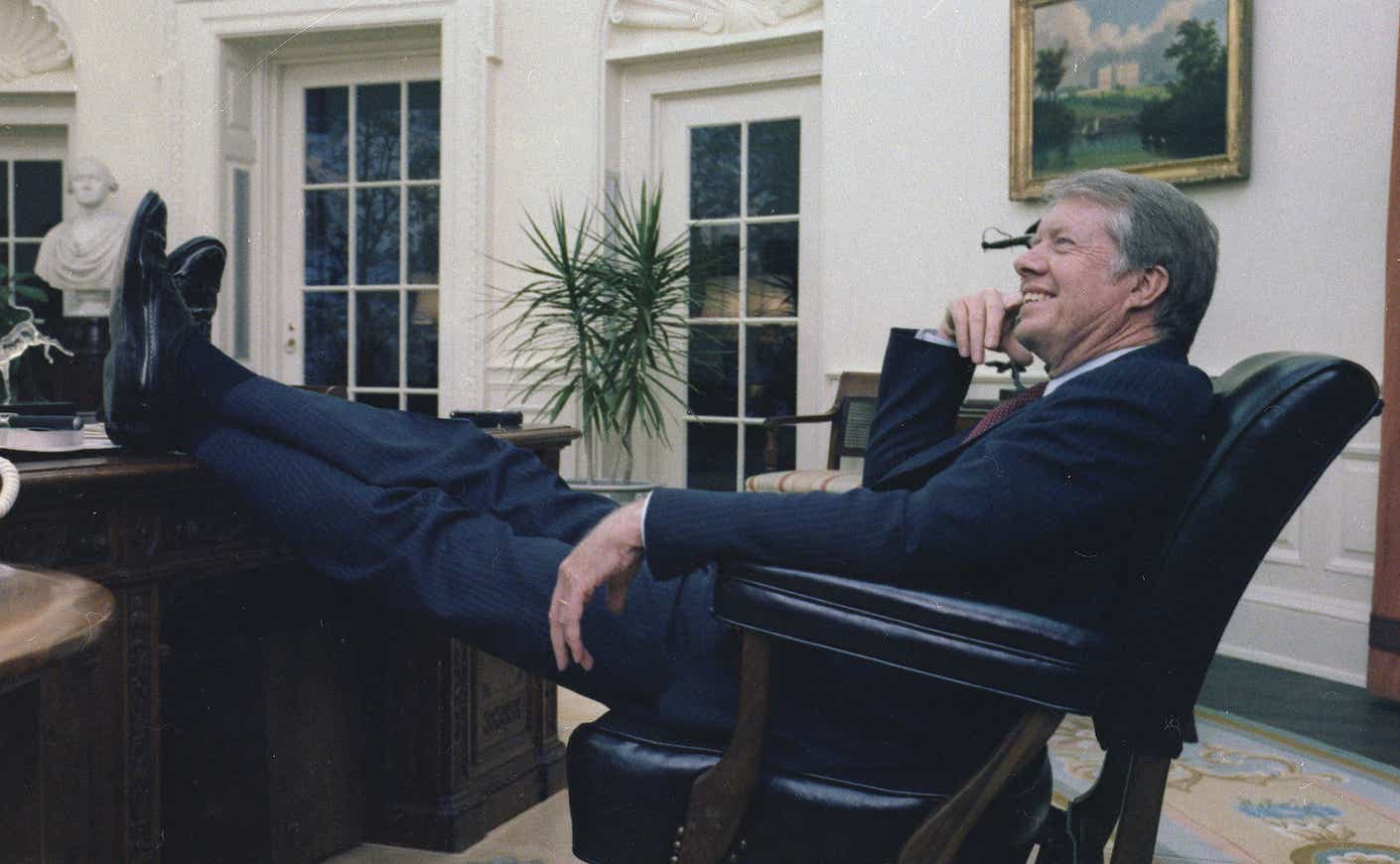

For decades after he was crushed in the 1980 presidential election, Jimmy Carter was defined as a loser. But on his 100th birthday, it's clear that — by any standard — he won at life. He's the longest-living American president, was the longest married (77 years, and happily), and — especially if you look at his whole career — is among the most accomplished and productive figures of our era.

As we celebrate this milestone, it’s time for the public to reassess this inspiring, complex, and confounding man. When I first began researching his epic American life in 2015, I was struck by the ubiquity of the easy shorthand on him — bad president; great former president. Even now, everyone from political scientists to the average person on the street will express this idea as if it’s an established fact.

The problem is, the widespread conventional wisdom on Carter is mostly wrong.

In His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life, I concluded that Carter was a hugely underrated president — a political failure but a substantive, visionary success. And he was a slightly overrated former president, despite essentially re-defining that role. In the four decades since leaving office in 1981, he certainly achieved plenty but he had much less power to change lives than he did while in office.

The Jimmy Carter I got to know in Atlanta (home to the Carter Library and Carter Center) and Plains (his birthplace and lifelong home), through extensive email exchanges, and while building a house with him and Rosalynn in Memphis, was a highly intelligent and paradoxical man: by turns, warm and chilly; open and opaque; able and tone deaf. One day I asked Rosalynn — who shared with me his steamy love letters from the Navy — if he was stubborn. She just nodded and laughed. I came to think of her husband as a driven engineer laboring to free the humanist within. He once told me that he could only express his true feelings in his poetry.

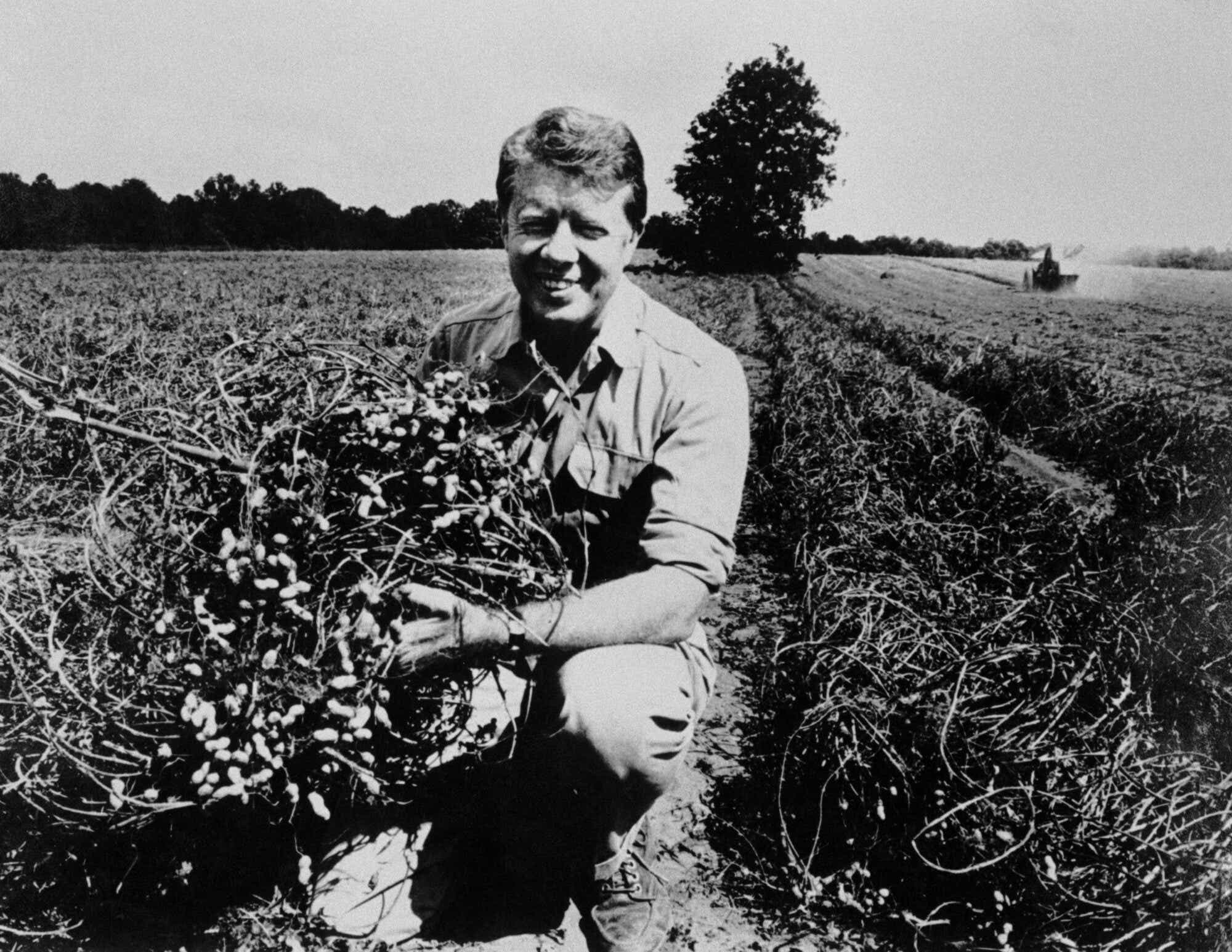

Carter led an extraordinarily colorful life — full of surprises — and he essentially lived in three centuries. He was born in 1924, but it might as well have been the 19th Century: His family, while prosperous for the area, had no electricity, running water, or mechanized equipment on the farm. He was connected to almost all of the major events and movements of the 20th Century. And the issues he tackled during his post-presidency — global health, democracy promotion, and conflict resolution — are the cutting-edge challenges of the 21st.

His father, Earl, was a white supremacist; his mother, Lillian, was a nurse who took care of Black sharecroppers for free and the only person in the county with anything nice to say about Abraham Lincoln. He was raised mostly by an illiterate Black farmhand named Rachel Clark, who gave him a love of nature and God.

As a child, Jimmy — nicknamed Pee-Wee because of his short stature — was driven by a dream of attending the U.S. Naval Academy, from which he graduated in 1946. He was later accepted into the most elite technology program of the mid-20th Century, Admiral Hyman Rickover’s nuclear navy, where he helped build one of the prototypes of the first nuclear submarine. When Earl Carter died in 1953, Jimmy decided to leave the Navy and return home to take over his father’s peanut warehouse. Rosalynn was so unhappy that she gave him the silent treatment all the way from upstate New York to southwest Georgia. (“Jack,” she told their 6-year-old, “tell your father he needs to stop at a rest area.”)

In his early adulthood, Carter ducked the civil rights movement. After the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, he served on the Sumter County School Board, where the historic decision ordering integration wasn’t even discussed, much less implemented. Doing so, under one of Georgia’s many Jim Crow laws, would have meant closing all of the schools. Such was his lot amid the white terrorism in Southwest Georgia in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Faith is an essential part of Carter’s life. In 1968, he underwent a slow born-again experience that included door-to-door Baptist missionary work in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. He even tried — and failed — to convert the madam of a brothel. But once he reached high office he became a strong supporter of a strict separation of church and state.

Carter was elected to the Georgia state senate in 1962 (after a local county boss literally stuffed the ballot box to steal the election from him) and he ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1966 as a (relative) liberal. At that point, he decided that he could either be governor or be an outspoken advocate of civil rights — but not both. So while he campaigned a bit in Black churches and never said anything explicitly racist, his second, successful try in 1970 included dog-whistle appeals to segregationists.

Just moments after being sworn-in as governor, Carter in his inaugural address announced that the time for racial discrimination was over. Many white supporters felt betrayed, while Black Georgians left the inauguration shocked but hopeful.

Carter then began using the second half of his life to make up for what he did not do in the first half, namely, stand up for civil rights. He integrated Georgia's state government and hung Martin Luther King’s portrait in the state capitol, while also amassing a highly impressive environmental record and challenging Georgia’s criminal justice system.

After leaving office in early 1975, he launched a brilliant presidential campaign that, with the help of the Watergate scandal and the support of “Gonzo” journalist Hunter S. Thompson, brought him from zero percent in the polls to the Democratic nomination. While briefly derailed by an interview in Playboy magazine in which the Southern Baptist confessed to having “lusted in my heart,” he won a narrow victory in 1976 over incumbent Gerald Ford, who had assumed the presidency after the resignation of Richard Nixon.

With skills ranging from agronomist, land-use planner, nuclear engineer, and sonar technologist to poet, painter, Sunday School teacher, and master woodworker, Carter was the first president since Thomas Jefferson who could rightly be considered a Renaissance Man.

He was also the first since Jefferson under whom no blood was shed in war. And his record of honesty and decency — once seen as minimum qualifications — have loomed larger with time. At a farewell dinner just before leaving office, his vice-president, Walter F. Mondale, whose job Carter turned from punchline into a position of real responsibility, toasted the Carter Administration: “We told the truth. We obeyed the law. We kept the peace.” Carter later added a fourth major accomplishment: “And we championed human rights.”

Carter did so by taking the American civil rights movement global and setting a new standard for how governments should treat their own people. While his human rights policy could be hypocritical — the U.S. continued to support the Shah of Iran and a few other dictators who served American interests — his new approach contributed to the demise of more than a dozen authoritarian regimes in Latin America and Asia. Two future heads of state — Václav Havel of the Czech Republic and Kim Dae-Jung of South Korea — credited their freedom from prison in part to Carter, whose words gave hope to thousands of dissidents and, even by some conservative accounts, helped undermine communism.

Carter may be best known for the 1978 Camp David Accords, the most durable major peace treaty since World War II. Israel and Egypt had fought four wars in 30 years when Carter brought Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat together for 13 days of talks at a rustic retreat in the Maryland mountains. At various moments, Begin and Sadat (a close friend of Carter) packed their bags and prepared to leave without an agreement. The deal was saved by Carter’s grit, which he showed again six months later when he went to the Middle East to painstakingly put the whole thing back together again before the White House signing ceremony. W. Averell Harriman, who served as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wartime envoy, called Camp David “one of the most extraordinary things any president in history has ever accomplished.”

While Israel and Egypt have maintained a chilly detente for four decades, the second part of the deal, a path to Palestinian statehood, has not been realized. Carter praised Begin for turning over the Sinai to Egypt but argued that he reneged on a pledge to freeze Israeli settlements on the West Bank until the completion of Palestinian autonomy. He believed that had he been reelected, he would have achieved a comprehensive Middle East peace.

Carter’s most far-reaching accomplishment may have been the normalization of U.S. relations with China. Richard Nixon opened the door and Carter walked through it. Within days of Deng Xiaoping's historic 1979 visit to Washington, Deng legalized private property and took other major steps toward a capitalist economy. Carter jettisoned Nixon and Ford’s awkward “two China policy” (which favored Taiwan) and established the bilateral relationship that — for all its problems — is the foundation of the global economy.

Another foreign policy victory came when Carter convinced the Senate to ratify the Panama Canal Treaties, which turned over the Canal to the Panamanians. Two-thirds of the American public were against the deal, but it required two-thirds of the Senate for approval — the heaviest of political lifts for a president so often derided for failing to bring Congress along. The treaties sharply improved the standing of the U.S. throughout Latin America and avoided a permanent deployment of more than 100,000 U.S. troops to Panama to protect the Canal from guerrilla attacks. But several Democratic senators lost their seats over the vote, and Carter won no lasting credit for preventing a festering Vietnam-style conflict in Central America.

Carter sharply increased defense spending and developed the B-2 stealth bomber and other high-tech weapons that years later helped win the Cold War — contradicting a rightwing canard that he was somehow “weak” on defense. After the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, he was forced to withdraw the SALT II Treaty from the Senate (though its terms were respected by both nations). Carter’s decisions to boycott the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow and impose a grain embargo on the Soviet Union were ineffective and, eventually, hugely unpopular.

At home, Carter failed to enact welfare, tax, and health care reform. But he still signed more domestic legislation than any other postwar president except Lyndon Johnson, much of it far-sighted. He established the Department of Education, the Department of Energy, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency; replaced tokenism with genuine racial and gender diversity in the civil service (which he revamped for the first time in 100 years) and federal judiciary; curbed the power of banks to “redline” (disinvest in) Black neighborhoods; and provided the first whistleblower protections and the first bureaucratic watchdogs (inspectors general).

Carter revolutionized not just the vice presidency but the role of First Lady, giving Rosalynn her own staff, diplomatic missions, and authority. It was Rosalynn who convinced the vast majority of states to require public school children to be vaccinated against polio, measles, mumps, and other diseases.

As in Georgia, Carter was far ahead of his time on energy and the environment. He placed solar panels on the roof of the White House (later taken down by Reagan), a symbol of a stellar record that included the first funding for green energy, the first fuel economy standards for autos, the first incentives for public utilities to use renewable energy, and the first federal requirements for toxic waste clean-up, among other far-reaching statutes. With the Alaska Lands Bill, Carter protected that state from being despoiled and doubled the size of the national park system. Had he been reelected, he planned to begin to address global warming, which was then an obscure problem even in the scientific community.

Anticipating the moderate “New Democrat” presidencies of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, Carter reduced the budget deficit and reluctantly approved a business tax cut. His appointment of Paul Volcker as chair of the Federal Reserve Board led to sky-high interest rates that helped cripple his presidency. But Volcker’s harsh monetary medicine eventually ended double-digit inflation — a victory whose political benefits accrued to Reagan.

In the second half of his term, Carter was beset by external problems, many of them beyond his control. Gasoline shortages led to a public “malaise” (which Carter addressed in a famous speech, without using the word). Senator Edward Kennedy, a darling of liberals, launched a damaging campaign against him for the 1980 Democratic nomination. After the seizure of the hostages in Tehran, the American public rallied around Carter for a time, which helped him fend off Kennedy. But when an April 1980 helicopter mission to free the hostages was aborted in the Iranian desert, Carter’s popularity sunk again — and his failure to unite his party after the Kennedy challenge didn’t help. After Reagan turned to the cameras in their only debate and asked viewers, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” the election was effectively over.

While Carter was unable to bring the hostages home before the election (perhaps because of a so-called “October Surprise” deal between the Reagan campaign and the Iranian government), he did so afterward — though the liberated Americans didn’t clear Iranian airspace until moments after Reagan was sworn in as president.

After leaving office, Carter wrote his memoirs and began devoting a week a year to building a house for Habitat for Humanity, helping spread the word about a small non-profit just up the road from Plains that eventually became the largest non-profit builder of housing in the world.

But Carter was depressed and at loose ends. One night in 1982, he woke up with a start and realized that he should build a conference center to bring peace between warring parties, as he had at Camp David. Carter’s major diplomatic successes both came in 1994, when (over President Clinton’s objections) he negotiated peace with Kim Il Sung, the founder of North Korea, and — along with Colin Powell and Sam Nunn — prevented a war in Haiti.

Over time, the Carter Center, which now employs more than three thousand people (mostly abroad), has allowed its founder to redefine what we expect from our former presidents. Embracing some form of public service is now the rule, not the exception, for (most of) them. Even so, Carter often quarreled with his successors. The bad blood between Carter and Clinton went back to 1980 when Clinton felt Carter’s decision to house Cuban refugees at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas cost him reelection as governor. President George H.W. Bush was appreciative of Carter’s help until he meddled in the run-up to the 1991 Gulf War. Carter had no relationship with Reagan and George W. Bush, and only limited contact with Donald Trump, who represents the opposite of everything Carter stands for.

The Carter Center has monitored more than 100 elections around the world but its greatest success has been in global health, especially the near-eradication of Guinea Worm Disease, which afflicted 3.4 million people when Carter began working on the problem, and now affects only a couple hundred. He also fought river blindness, Ebola, and other diseases, and Rosalynn did important work in lifting the stigma of mental illness.

Even after beating melanoma in 2015, Carter continued his work as a peacemaker and promoter of human rights and democratic accountability. And he taught Sunday School at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains until he was 95.

In recent years, the shortcomings and contradictions of his long life have given way to an appreciation of his core decency. Now, we are left with his example: a life of ceaseless effort, not just for himself but for the world he helped shape.

Jonathan Alter is an award-winning author, political analyst, documentary filmmaker, columnist, television producer and radio host. He's the author of three NYT bestsellers, and his latest book is His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life. He also pens the OLD GOATS: Ruminating With Friends Substack, where he has conversations with people of wisdom and experience to help readers grapple with a wide variety of historical, political and cultural questions.