Over the next few weeks, in anticipation of Katie's book release, we'll be sharing exclusive excerpts that didn't make the final cut. (There was too much good stuff to fit into one book!) This week, in recognition of the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, and as Hurricane Ida plows through the South, Katie remembers traveling to New Orleans back in 2005.

As a reporter, I always loved being out in the field, telling personal stories that would make viewers and readers care — exposing the incompetence of both the local and federal government. But what I experienced in New Orleans was something I never could’ve prepared for.

It was the tail end of my vacation (we had rented a house at the beach with our family friends) when maps with ominous hurricane symbols started popping up on TV. When Katrina began picking up steam and became a category 4 hurricane cutting across South Florida and turning right toward the Gulf Coast, I left my daughters with our friends and drove back to New York. It was a huge story. I couldn’t justify frolicking on the beach and eating corn on the cob knowing this was going on.

I’d covered hurricanes before, but I’d never seen anything quite like this. Huge, violent waves crashing into storefronts, trees blown horizontally, fires shooting up from gas leaks, an aerial view of people standing on submerged cars and houses with only the rooftops above water. The hurricane itself wasn’t the problem. It was the fact that the levees in New Orleans had been breached, and the Crescent City was underwater.

As soon as I landed in New Orleans, I met up with Audrey Kolina, a west coast producer who had become a good friend, on the roof of a building on high ground and jumped into a helicopter, where a police officer took me on a tour of the city.

As he talked me through the devastation he said, “This has all the makings of a horror movie. The sadness. The destruction. The pain. It breaks your heart...Once we begin the recovery operation, we’re going to find a lot of dead people.”

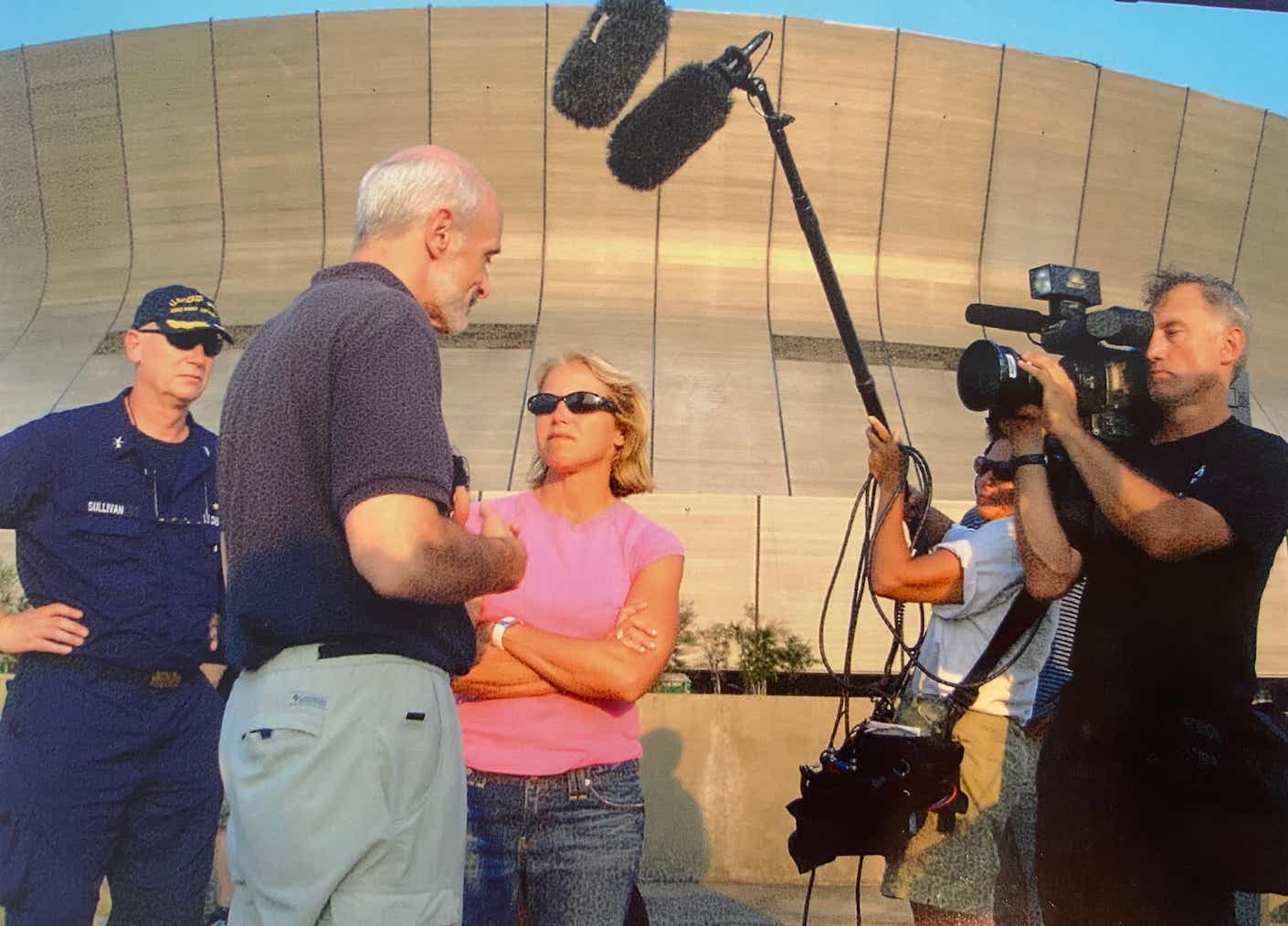

I ran into Michael Chertoff, the Secretary of Homeland Security, who told me, “We’re doing a tremendous job here. The goal was to go house by house, room by room to find the remains of people. Our mandate here is, ‘recovery with respect.’”

Police Captain Defillo told me a fellow officer thought he’d lost his family in the flood, had driven to an area of town and shot himself. It turned out his family had survived. One fellow officer, a man named Paul, couldn’t deal with the idea that so many were being left to die. He took his own life as well.

Later we drove past a long line of New Orleans police officers who were getting shots for hepatitis and tuberculosis after recovering bodies and wading in contaminated water. Some people, I was told, were waiting to be rescued, having spent seven or eight days trapped in their homes without food or water, in unbearable heat. I heard that morning they had retrieved an 11-year-old boy from his house. His mother was dead in the attic.

The mandatory evacuation was put into effect only 19 hours before the hurricane reached landfall, and thousands had fled to the Superdome and the New Orleans Convention Center, both bursting at the seams with people surviving in squalor without food or plumbing. Meanwhile, President Bush was flying over the devastation, looking out the window of Air Force One. The photo of that moment, a symbol of a detached President completely out of touch.

We had set up shop outside the local affiliate in New Orleans. The producers had somehow found us trailers to sleep in. There wasn’t enough space for everyone, so we took shifts in the middle of the night — one person would sleep from 8 p.m. to midnight, the other from midnight to 3 a.m. until it was time to start setting up for the show. Researchers and producers were sleeping on tables, chairs, the floor. Audrey and I ended up sharing one of the twin bunk beds — the logistical nightmare of doing a remote show at a moment's notice.

On Tuesday, I reported from Central City. Wearing waders, I interviewed the Essex family, including their 2-year-old grandson, as they stood on their front porch. They, like so many others, were refusing to leave, telling me this was home. But what they didn't say was that they were protecting their house from looters. I told them there were diseases they could get from contaminated water, that the gas leaks could turn into fires. But Mr. Charles Essex was undeterred. Holding his grandson he told me, “Maybe now people will really understand what we’ve been talking about all these years.” These conditions pre-dated Katrina; many had felt abandoned long before.

We planned to continue the story from Texas, where 250,000 displaced people had escaped to starkly different conditions. The Houston Astrodome had become a sanctuary for 16,000 Katrina refugees from across the Gulf region. I was so moved by the warm welcome they received, along with hot showers, medical attention, and three meals a day. Such a contrast from the Superdome in New Orleans.

Rows upon rows of cots were lined up on the floor of the arena. I had never seen such a sea of humanity: an old lady staring into space, oblivious children playing Candyland, a mother and her infant lying on a blanket on the ground sleeping soundly. Many were still separated from their families — a big sign in front of metal barriers had large letters that said, “LOST CHILDREN.”

One man had been wandering around with a small photograph of his grandson in his kindergarten cap and gown. He told us that he couldn’t find his wife, daughter, or three grandchildren then looked at me and said, “Help me, please, Katie.” It was about the saddest thing I had ever seen or heard. That simple, desperate sentence conveyed the anguish and desperation of so many people. A few days later, we showed him reuniting with his family. I still think about him often.

When I closed the show in Houston, Matt said “Katie, you’re headed back. Is that true?” To his surprise, I said, “I’m not sure where I’m headed Matt, but I know I’ll talk to you tomorrow.”

We’d been traveling for days but I realized we couldn’t fully tell this story without going to the other major city that had been impacted. So, the next day we traveled to Biloxi, Mississippi.

Katrina wasn’t an equal-opportunity destroyer. Poor Black communities were decimated: Among the 971 Hurricane Katrina victims who died in Louisiana, more than half were Black. In the affected areas of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, more than 90,000 people had incomes of less than $10,000 per year, and 16 percent of New Orleans’ affected households were very low income.

Unfortunately, 16 years later, New Orleans still hasn’t fully recovered from Katrina, but the city and its inhabitants are currently facing another formidable force: Hurricane Ida. The levees, floodwalls, and floodgates that failed New Orleans 16 years ago held up against Ida (the federal government spent billions of dollars on an upgrade). But, as of Tuesday, Aug. 31, hundreds of thousands of Louisianans were suffering in Ida’s aftermath with no electricity, no tap water, very little gasoline, and no end in sight. A million people remain powerless in Louisiana, including all of New Orleans.

If predictions about climate change are accurate, we’ll likely see more tumultuous weather patterns in the future. Hurricanes may make for dramatic television, but long after the network crews pack up their equipment, the widespread misery — particularly among the poorest communities — lingers on for weeks, months, even years. Mother Nature has a dark side. That’s when human nature comes in — compassionate neighbors and organizations coming to the aid of people in need.

If you’d like to help, New Orleans officials have recommended donating to United Way of Southeast Louisiana and The Greater New Orleans Foundation.