This year, the main stage of the Clinton Global Initiative’s annual meeting was called “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once” — and the name was fitting. After all, the topic at hand was the question of how we can possibly solve the all-encompassing, overlapping, ongoing global challenges and conflicts. As a moderator, Katie dug into the life stories and professional experiences of four changemakers whose organizations and businesses have undertaken different solutions to humanitarian disasters, environmental issues, and class inequality.

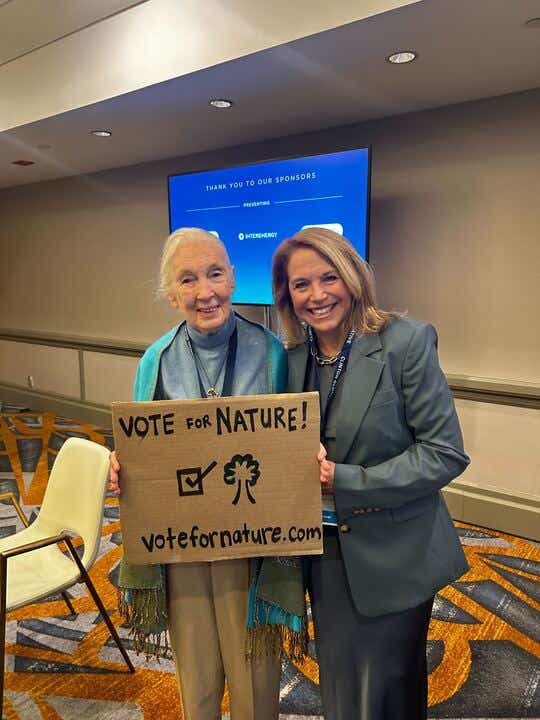

Katie first interviewed legendary primatologist Jane Goodall, founder of Roots and Shoots, alongside chef José Andrés, the founder of World Central Kitchen. Goodall and Andrés both spoke about their inspirations for starting nonprofits and how they were able to use their talents and skills to respond to disastrous situations.

Andrés, whose organization provides meals as disaster relief, reflected upon the devastating loss of seven team members who were killed by Israeli airstrikes in Gaza: “I was supposed to be there, I was tired, and that's why I wasn’t there. The people that died, some of them were good friends. But we need to remember that before those seven non-Palestinians perished, hundreds of other humanitarians perished — on top of civilians.”

“I realized that in the worst moments of humanity, the best of humanity shows up,” he continued. “When I was in Israel where we were feeding [people] in the kibbutz next to Israeli chefs, many of them said, ‘I would love to go to Gaza to show solidarity with the people of Palestine.’ And I had Palestinian women telling me, ‘If I could go to Israel, I would go there to tell them that I don't have anything against them.’ These are the voices of humanity. That's what I see in the world.”

Goodall spoke specifically about the shocking experience of witnessing massive deforestation in Africa during the mid-1980s: “I flew over Gombe National Park, which had been part of a great forest belt across Africa. I was shocked. It was a little island of forest, and the hills around it were bare. People were cutting down the forest because they were struggling to survive and they needed money from charcoal or timber…So we started a program to help the local people find ways of making a living without destroying the environment.”

Katie also chatted with Laurene Powell Jobs, founder of the Emerson Collective, and Hamdi Ulukaya, the CEO of Chobani, both of whom have experimented with new models for for-profit businesses. Jobs explained how for-profit businesses could call more attention and bring more capital to dire causes: “While we have a deep and highly rewarding philanthropic practice, we also find that using for-profit companies — and entrepreneurs who want to create for-profit endeavors that are mission-aligned — can make philanthropic work so much more powerful. It's like rocket fuel.”

Ulukaya, as a for-profit company founder, told Katie that his own mission-aligned organization changed his community.

When he first landed in upstate New York after immigrating from his native Turkey, Ulukaya was disappointed by the state of American yogurt: “It was candy.” He noticed, however, that upscale stores sold the good stuff: “You go to some fancy store to shop, and they have some yogurts from Greece. I couldn't understand why your income could determine what kind of yogurt you eat.” After reopening a shuttered factory so he could churn out affordable, high-quality yogurt, he witnessed the positive results that new business could bring to a community: “The farmers were busy, the house prices were going up.”

“If I figured it out, [we] can figure out anything,” Ulukaya emphasized. “If the human spirit can come together, we can figure out how to come out of any trouble.”