Paul Delaney: “What you’re seeing is going to be in the history books… Act accordingly”

As a young Black reporter right out of journalism school in 1958, Paul Delaney was rejected by 50 newspapers. He finally found his first job at the Atlanta Daily World. Later, he became an editor at the New York Times, and helped found the National Association of Black Journalists. Through his reporting, Delaney brushed shoulders with iconic figures in the Civil Rights Movement, including Martin Luther King, Jr. himself.

On April 4, 1968, Delaney, then a reporter at the Washington Star, was out to dinner with some colleagues in Washington D.C., when a waiter delivered fateful news: MLK Jr. had been shot. In a new interview with Katie Couric’s Wake-Up Call newsletter (subscribe here!), Delaney reflects on the long night that followed — and shares advice for journalists covering the movement now.

Wake-Up Call: Where were you when you heard that Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated? Describe the exact moment.

Paul Delaney: I was working for the Washington Star. In fact, it happened right after work. A group of us was drinking and eating dinner on Capitol Hill when he was shot. We had been drinking and had just ordered dinner. I was drinking scotch on the rocks at the time. Our waiter came up and told about six or seven of us — one editor and reporters — that Dr. King had been shot.

We jumped up, canceled dinner, and ran back to the paper. In those days as the papers were overwhelmingly white, most of the staff stayed in the suburbs. So when we got to a paper there weren’t any editors around. And we knew that the town was going to blow, so we just started assigning ourselves. That’s how we started on the King night. We knew where the biggest problems were going to be. And we went right there.

What did you see when you got to the parts of the city where protests were starting?

By the time we drove up there, the fires had started. We were in the middle of rioters, setting fires and looting stores. Two or three cops were around, but they were totally overwhelmed and they did nothing. My partner and I just walked several blocks, taking notes and watching the action. We thought, you know, ‘The mayor lives nearby. Let’s go by his house and see what’s going on.’

So we went by, and he let us in. He was shocked. We suggested to him, ‘You know, you have to take a ride and take a look at what’s going on.’ My partner went back to the paper to start writing our story, and I rode in the mayor’s limo.

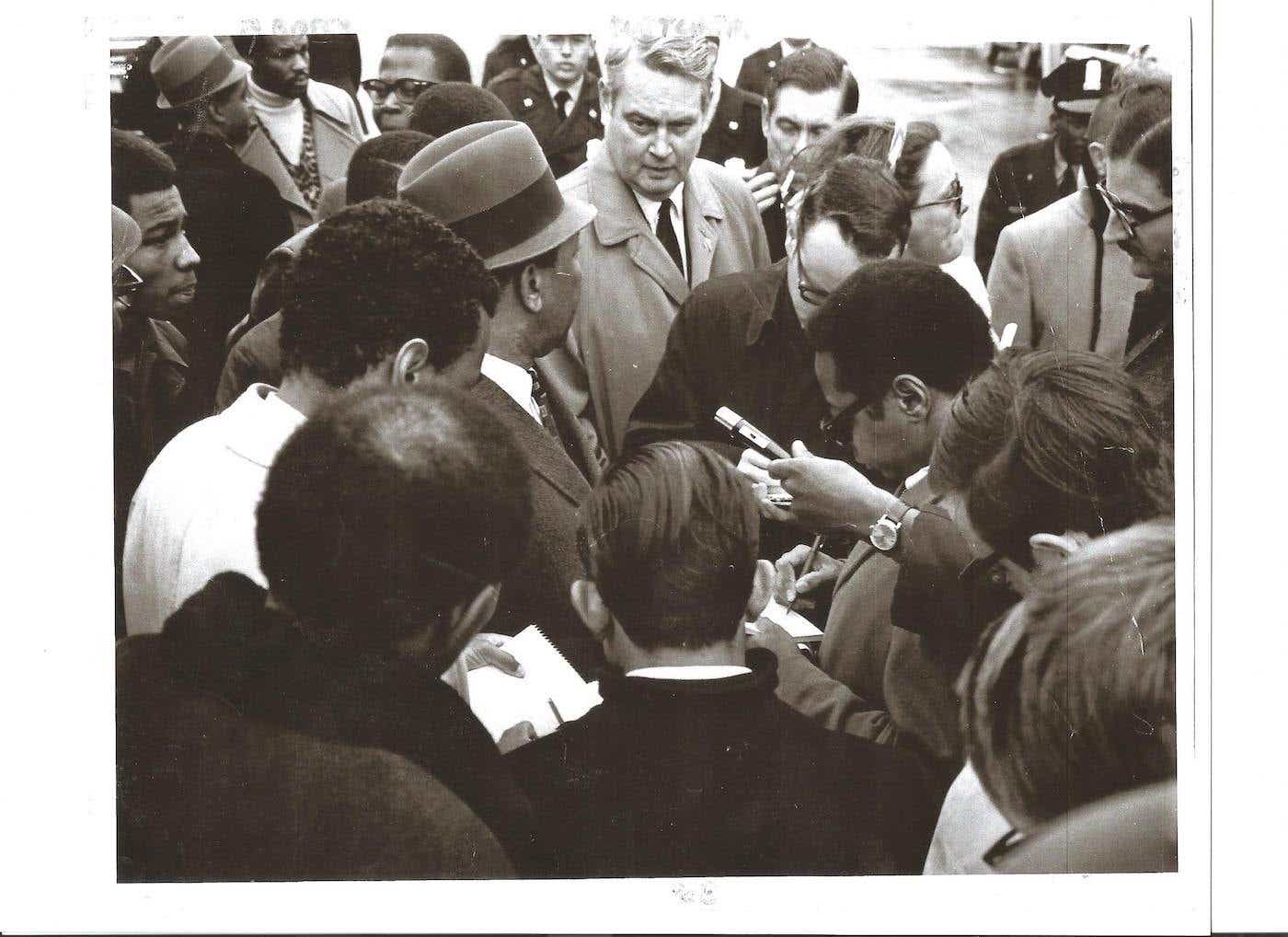

I worked all night. I went home at about 5 or 6 a.m. after filing my story. I got two or three hours of sleep and then came back. And that’s when the National Guard started marching in. The looting had stopped, and the authorities had taken over so we started covering the damage. We did a lot of follow up stories. The next day for example, the mayor toured around the area and I followed him around that.

It’s interesting to hear how many parallels there are today, as the National Guard was in D.C. recently. What was it like to see the National Guard marching in back then?

The first time I had been to a military country was Franco’s Spain. I had never seen anything like it. And so it was amazing to me to see armed soldiers on every corner. It reminded me of my only time in a country with a dictatorship.

Today, many journalists have run into problems while covering protests, even being arrested and experiencing violence. Did you experience any issues?

Paying attention to me? They were busy. On another occasion, a different mini riot, my buddy and I were taking notes, and every time the rioters would come by, we would pretend we were part of the group.

My friend, who worked for the Washington Post, found a telephone because we needed to call in our stories. I’d watch out for him while he was on the phone. And when the kids came by yelling and screaming — we’d put the phone down and whistle like we were part of the group. And then he’d get back on the phone and finish calling in his story. This went on all night.

Did you ever meet Martin Luther King Jr.?

Before I came to Washington, I worked in Atlanta when the Civil Rights Movement started. When King moved his headquarters from Montgomery to Atlanta, my work was three doors down from his office.

We used to see him all the time. We used to go up in the office and talk about stuff. And everybody came to town just to participate in the movement — movie stars, writers, from Harry Belafonte to James Baldwin.

So you saw the evolution of the movement from the very beginning. How did it compare to what’s going on today? Do you see any parallels?

The looting today was not as bad as it was back then. I don’t think there’s a comparison to rioting that happened. And the Civil Rights movement was integrated, but it was overwhelmingly Black. The demonstrators were Black. A lot of the white people who participated were not Southern white people. They were white people who came in from the North.

Nowadays, the crowds are overwhelmingly white and much more integrated. Back then, they were just trying to get rid of segregation. And now they’re trying to get rid of all of discrimination. Also today it’s nationwide. Just about every state has the movement. That did not happen in the ’60s. So this is bigger, wider, and deeper.

You helped found the National Association of Black Journalists. Why do we need more voices now, more than ever? Why is it so important?

America’s makeup has changed from overwhelmingly white to just about even now. Eventually, if it isn’t already, it’s going to be majority nonwhite. The media has to adapt. We called for that back when we formed the NABJ. And we’ve got to take that into account.

We need more diverse voices, because we need reporters and editors who’ve had different life experiences. We need people who understand, and are sensitive to certain issues.

From what you’ve observed, why do you think this moment in history might be different?

This is bigger. It’s nationwide. The main difference is that a lot of people are coming to their senses. They’re seeing things that they never saw before, and are changing their minds. And now that the demonstrations are mostly white — that’s a major factor.

Back in the day, I was excited about being a reporter because I knew this was history in the making and that was exciting. I urge journalists today to stay fair and objective and follow the ideals of journalism. What you’re seeing is going to be in the history books — be aware of it and act accordingly.

Correction: This has been updated to reflect that Delaney’s first job was at the Atlanta Daily World and that Walter Washington was the D.C. mayor.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This originally appeared on Medium.