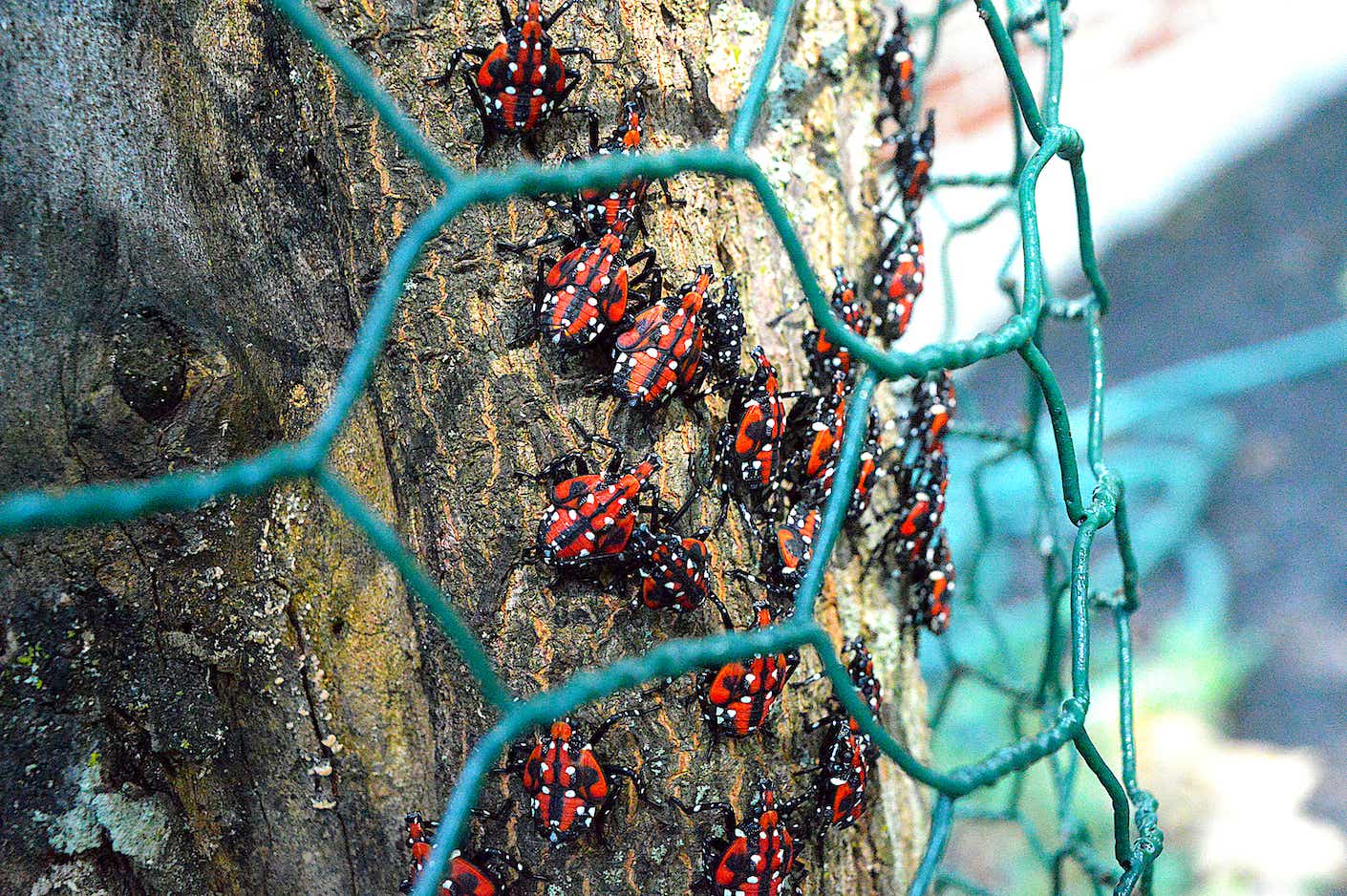

If you’ve been out and about in a number of states this summer — particularly New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania — you may have seen a striking new pest called the spotted lanternfly. A planthopper indigenous to parts of Asia, spotted lanternflies are about an inch long, half an inch wide, and as you can probably guess, have spotted wings. Their hind wings have red-and-black patches with white in between. Contrary to what their name might lead you to believe, these critters don’t actually light up — fireflies, in the beetle family, are the ones that do that. The bugs were first spotted (pun intended) in the U.S. in Pennsylvania in 2014. But don’t get distracted by their unique appearance — the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service warns that lanternflies are an invasive species that feeds on a variety of trees, including fruit trees. If allowed to spread, they could disrupt the grape, orchard, and logging industries in the U.S. That’s why you may have seen PSAs instructing people on how to squish lanternflies if they see them. But with some recent outspoken support for the insects’ survival, is killing them on sight really the best way forward?

Why are spotted lanternflies dangerous?

They don’t bite or sting humans, nor do they hurt pets, so how harmful could they really be? Turns out, if left unchecked, quite. Damaged grape vines in South Korea, where the species was accidentally introduced in 2007, seem to correlate with the bug’s arrival, and South Korean vineyards saw a decline in the total number and quality of grapes. Studies have projected that an infestation in Pennsylvania alone could cause $324 million in damage.

The USDA warns that a number of types of trees could be at risk, including ones that grow almonds, apples, peaches, and other stone fruit. Also potentially on the chopping block are oak, pine, poplar, and sycamore trees, among others. So far, spotted lanternflies have been identified in 12 states, with the USDA warning that most states are considered at risk. So if you enjoy summer fruits or sitting under a big willow tree, it’s time to pay attention and keep your eyes peeled.

How to kill a spotted lanternfly

Check the USDA or your state government’s website for resources on identifying these critters at all stages. Be sure to check trees and outdoor items like furniture for egg nests. If you see a nest, scrape it into a Ziploc bag filled with hand sanitizer (or a bucket of hot, soapy water), then throw it away and report the sighting to your state’s Department of Agriculture.

If you see a mature lanternfly, you can simply squish it, then report it.

Should we kill spotted lanternflies?

For some animal rights activists, the idea of going out of one’s way to kill a living thing can be a tough pill to swallow. A PETA spokesperson told The New York Times that people should carefully consider “killing any living being, no matter how small or unfamiliar.” But government officials emphasize that the risk is too great to let pity for these seemingly unassuming creatures take over. A spokeswoman for the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture told the Times that some vineyards in southeast Pennsylvania have lost over 90 percent of their crops because of the newcomers.

Perhaps a more legitimate criticism of the squishing campaign is that it might not be the most effective strategy — the species’ numbers are growing, its population spreading to different states across the country. Researchers at Lafayette College found that controlling reproduction, not killing the bugs once they’re mature, may be the better way to fight an infestation.

Earlier this month, Senator Chuck Schumer outlined a plan to bolster the USDA with an additional $22 million in federal funds to fight back against the unwanted pests. “The spotted lanternfly is no longer just a threat to New York, it’s here, and it’s ready for its closeup,” Schumer said. Those uninterested in killing them can still help out by reporting their location. In a Spotted Lanternfly Alert, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture warned, “These are called bad bugs for a reason, don’t let them take over your county next.”