This story was originally reported by Alexis Wray, Eden Turner and Sabreen Dawud of The 19th. Meet Alexis, Eden and Sabreen and read more of their reporting on gender, politics and policy.

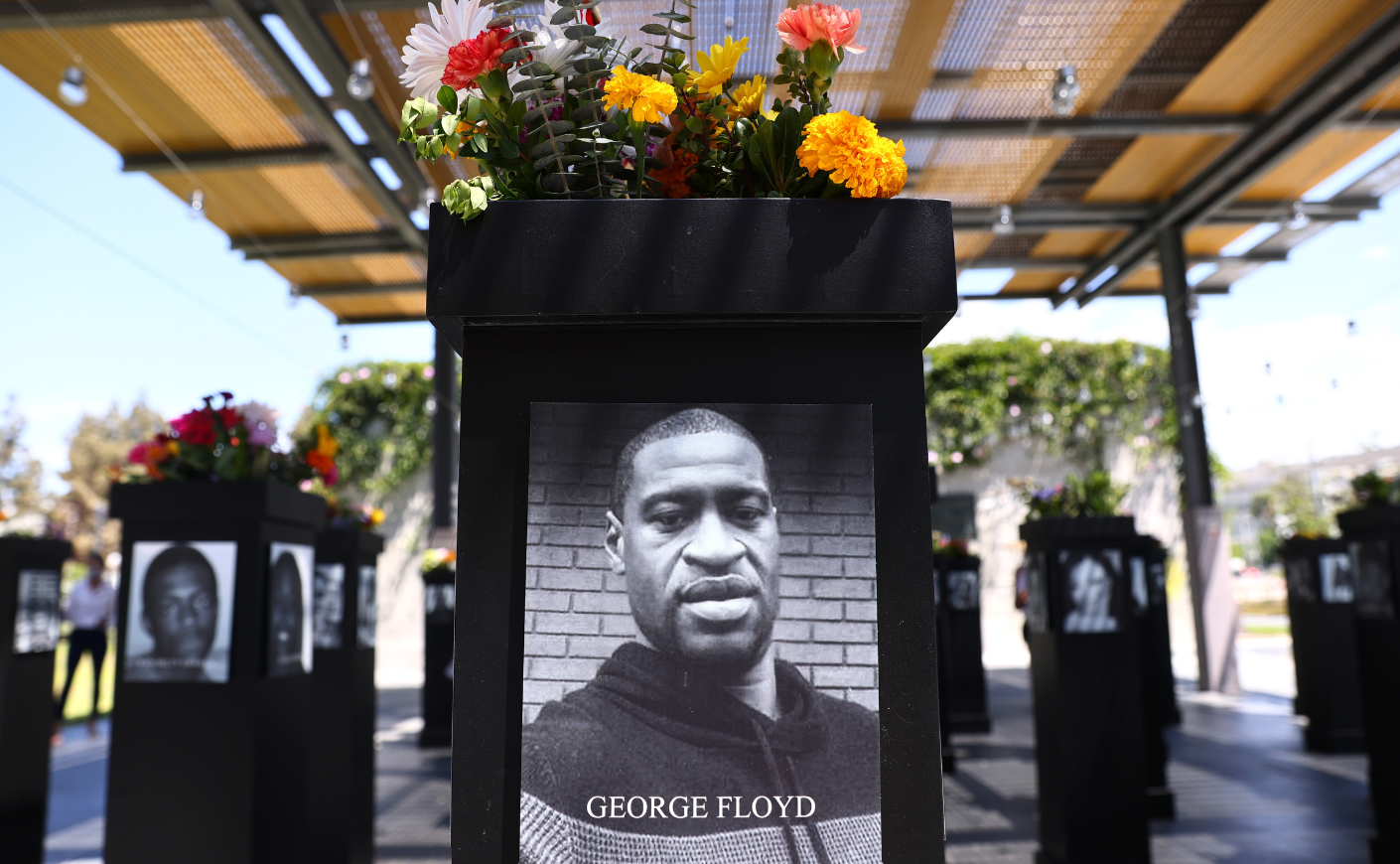

The fifth anniversary of George Floyd’s death is approaching, a time that many remember as a “racial reckoning” that heightened the world’s attention on police brutality and its deadly impact on Black people.

Activists, leaders and community members believed five years ago that the country would point to this moment as the one that brought lasting change toward racial equity. Now, the majority of Americans say that moment has passed with its promise unfulfilled.

In a study published on May 7, the Pew Research Center found that in 2020, 52 percent of U.S. adults believed that an increased focus on racial issues across the country would lead to significant change in the years to come. In 2025, 72 percent of U.S. adults said that the focus on racial inequality did not lead to any changes that helped the Black community.

Furthermore, in 2025, 67 percent of Black Americans said they felt doubtful the United States would ever achieve racial equality; 65 percent felt similarly in 2020.

The 19th spoke with Black activists about the country’s progress toward equality since Floyd’s death and how they envision a more inclusive future.

‘You have to do things to actually show how you feel’

Alaunna Thompson was attending a predominantly White high school in Montville, N.J., when Floyd died. His murder was a call for her to organize a protest in her local community, she said, describing her ongoing struggles with racism in school as the driver that pushed her to use her voice.

Protestors gathered at Mackay Park in Englewood, N.J., to demand justice after Floyd’s death. Following a route that led them around the city, participants stopped to deliver passionate speeches and craft signs that they would carry while organizing. Parents, teachers, students and Englewood residents all came out to support.

“It was a mix of us feeling some way about our school and on top of that, hearing all this stuff [about] Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd. It was back to back to back.”

Arbery was a 25-year-old Black man who was shot and killed while on an afternoon jog in the Satilla Shores neighborhood of Georgia. Arbery’s death happened in February 2020, just months before Floyd’s.

Thompson remembers feeling sadness, anger and disbelief. With the stunting pain also came the realization that this time, something felt different.

“I saw people talking about [Floyd’s] drug charges and the things he did, and I was just, like, ‘Wow, this is really sad,’ and I felt angry about it. Honestly, I thought nothing would happen,” she said. When Derek Chauvin got arrested and convicted in federal court of killing Floyd, “that was a shock to me,” Thompson said. “That’s never really happened before.”

In Thompson’s eyes, while Floyd’s murder did not put an end to racially motivated violence, it did shift our social understanding of how we discuss police brutality. Up until the day of Floyd’s death in 2020, she had never witnessed so much language that reflected how brutal police violence is.

“People are more comfortable holding these police officers accountable now. I think versus the Trayvon Martin period, people were [thinking] these are not people who are going to get prosecuted because they are above the law,” she said. “They’re also more comfortable saying that this person killed this person instead of it being police brutality. This is murder.”

At just 17 years old, Martin was shot and killed while walking in Sanford, Florida. His killer, George Zimmerman, was the captain of Sanford’s neighborhood watch and reported to police that he saw a “suspicious person” prior to shooting Martin. Zimmerman was later found not guilty in the trial.

Although Thompson does not feel there has been effective systemic change in the five years since Floyd's life was taken, she does recognize the impact that he has had. Her place in history is what will continue to compel her to use her voice, she said.

“It’s about history. It’s not about two little kids from Englewood who may not make that much of a difference when it comes to the law, but it makes a difference when it comes to which side of history you were on.”

‘I hope many people hold onto … the possibility that lies ahead’

Throughout her life, Angela Ferrell-Zabala has looked to the strength of her mother and grandmother to inspire her activism. At a young age, her family instilled in her the belief that she has a voice and the power to advocate against injustice in the world. As she grew older, she followed their lead in the work she’s done for her community.

As a mother of four living in Washington, D.C., she wanted to do something about gun violence in the city. So she joined Moms Demand Action, a gun violence prevention advocacy group. Three years ago, she became its first executive director.

Ferrell-Zabala felt that Floyd’s murder was a continuation of violence against Black and Brown people that had become normalized. While she helped the people in her community, she had to remember to give herself grace to deal with the emotional turmoil she was also experiencing.

“In the moment, you just want to make sure everyone’s OK,” she said. “You want to wrap your arms around them, but then there’s this point about ‘What do I need?’”

Five years later, Ferrell-Zabala said that it’s a hard moment for the country — and a hard moment for Black folks in particular. Decades of pain and trauma are continuing to impact the Black community, and many in the community feel like no one cares about the struggles they are facing.

For instance, Ferrell-Zabala said that Black people are disproportionately impacted when it comes to gun violence, and communities say that solutions aren’t meeting their needs fast enough. With corporations and the federal government rolling back inclusive programs that civil rights leaders fought hard for, many people have lost hope.

“Right now, it feels particularly difficult because there’s this sense of, ‘No one cares, no one gives a damn,’” she said. “But I think what makes it harder [is that] now, it’s beyond not caring. It [feels] like intentional cruelty.”

Ferrell-Zabala told The 19th that the country has a long way to go when it comes to creating true equality, equity and justice. She looks to her grandmother’s resilience as a reminder to keep working toward a better future. To move forward, she said that the Black community has to think about where they are and balance it with their radical visions of what could be.

“That’s one of the things I hold onto,” she said. “I hope many people hold onto who we are, where we come from and the possibility that lies ahead.”

‘We're the only thing protecting each other’

Destine Riggins saved on her phone an album of pictures labeled Black Lives Matter March. She took these photos five years ago in West Jefferson, a town in the rural Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. She was the sole photographer there.

Riggins used to look at the photos and see impact, unity and change. Now, when she looks at them, Riggins said she feels like “the whole world is against us again.”

“I feel like we're in a worse scenario right now than we were five years ago. With the current administration we have, police brutality is easy for them to slip under the rug or even for a policeman to get off, especially with [President Donald] Trump wanting to pardon officers,” Riggins said.

Floyd’s murder immediately made Riggins think of Trayvon Martin and Sandra Bland, a Black woman roughly handled and arrested by the police in Texas and then found dead in her cell a few days later by what the local police consider suicide. There was also Sonya Massey, who was shot and killed in her home by the police last summer.

Since the march, Riggins has watched the national conversation around race and policing shift, making her feel tired, heavy and more unsure than ever.

“Each time we see these murders by the police it feels like another hit to the Black community. Another disappointment. Another reason to not like the cops. And another reason for a White man to be able to kill a Black man,” Riggins said.

Millions of people across the country have been protesting against the Trump administration through efforts like the Hands Off and 50501 movements. Many Black communities have decided on other forms of resistance and several people, like Riggins, are choosing to turn inward, by resting and leaning on their community for support.

“There is no protection for Black people except us, we're the only thing protecting each other and right now that feels kind of disintegrating. My biggest opinion is to lay low right now,” Riggins said. “I don't want to bring any extra attention to myself because I don't have time to try to fight a justice system that was never meant for me in the first place.”

‘Police brutality shouldn't just be personal to Black people’

While Riggins took pictures, Queue Wellington helped lead the march in West Jefferson, where more than 300 people protested in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Growing up Black in a rural, White, conservative and poor region, Wellington constantly saw how white supremacy and police brutality negatively impacted everyone.

“White people love to cling to power, but that power is white supremacy. As this country continues to lean overtly more into fascism and acceptance of police brutality, then that means Black people will keep dying, White people will keep dying and everyone will keep dying — largely by the hands of the police or people in power,” Wellington said.

After the summer of 2020, Wellington saw an increase in White people in their town attempting to unlearn anti-Black behavior, understand systemic issues and work in community with Black movements. Since then, they said those same people have faded away and that their actions were likely performative.

“There was a wave of White people trying to become more conscious or get more informed on things, but where are they now?” Wellington said. “Black people have always had to juggle it all at the same time: work, bills, lives and oppression.”

While Wellington feels that things aren’t better for Black Americans since the summer of racial reckoning, they do believe that at least more White people are grasping the reality of police brutality.

“If we can't get a thousand White people to understand, maybe having one White person on board or seeing the reality of police brutality will change things or even create safer environments for Black folks,” Wellington said.

Wellington thinks this understanding could even be found in places like the Appalachian Mountains, where Stuart Mast, a White man, died while in deputies’ custody in a similar way to Floyd.

Several community members are outraged by Mast’s death, and people who once “backed the blue” are now questioning the system that police brutality has created.

“The fact that White people in my community are outraged over police violence feels oddly familiar. We should all be asking why folks are getting killed by the police. This murder has started to cause a divide between the police and White people here,” Wellington said. “Police brutality shouldn't just be personal to Black people, but to everyone because it affects everyone.”

‘Our joy has to be non-negotiable’

In 2020, Monica Simpson and her community felt caught in the middle of challenging moments: Trump was finishing his first term and the COVID-19 pandemic was at its peak.

As the executive director of SisterSong, a reproductive rights group based in Atlanta, Simpson joined other members to create mutual aid opportunities for those in need and help pregnant women get access to birth workers.

Then Floyd was murdered. When the news broke, Simpson was immediately reminded of the other Black men and boys who were murdered by White men, such as Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice — and the list keeps going, she said. But it felt like the world had to keep moving forward. Simpson had to continue doing the work for her community.

“We were having to still hold our community in all the ways that we need to for the work that we do every single day,” she said. “We had to be on the frontlines at the same time.”

At that time, the country saw what the media called a racial reckoning and Simpson felt that it took away from the grief the Black community was feeling after Floyd’s murder.

In 2025, with Trump back in power and making more changes to disenfranchise marginalized communities, Simpson feels that Black communities did as much as they could to restore what Trump’s 2016 administration destroyed. Black-led advocacy organizations came together, despite their contradictory beliefs, to put forth the work necessary to help their communities and each other.

Overall, Simpson said the Black community knew a second Trump presidency “would be detrimental.” Ninety-two percent of Black women voted for Kamala Harris during the 2024 presidential election and mobilized their communities. During his first five months in office, Trump has made strides to roll back diversity, equity and inclusion programs and positions in the federal government, and many corporations have followed suit.

“I think we’re in more danger now than we were before,” Simpson told The 19th. “We’re in the same position of our rights, our bodies, our communities being under attack.”

To create a more inclusive future, Simpson said that the Black community must continue to work together across religions, political values and identities because "disrespectability politics … have kept us divided.” The Black community has to come together to advocate for their needs, which includes educating each other, reclaiming their culture and embracing moments of joy.

“We need all the Black joy as possible because our joy has to be non-negotiable at this time,” she said. “That’s a powerful and necessary part of how we make it through.”