A deadly conflict has overtaken Ethiopia, yet it’s barely made headlines in the West. The country’s protracted civil war has continued unimpeded by outside intervention — even as reports surface describing rape, slaughter, and starvation tantamount to genocide.

We’ve got a bird’s-eye view of what’s going on — plus some heartrending insight from a couple who’ve experienced the horrific reality firsthand.

How did the violence begin?

At the beginning of November 2020, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, ordered a military assault in the northern Tigray region. His target was the region's former ruling party, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF). The result has been a year-long battle that’s left famine and a slew of other atrocities in its wake — often committed by Ethiopian forces against citizens.

By November 2021, the Ethiopian army had suffered such heavy front-line casualties that the government began calling on ordinary citizens to join the fight against the Tigrayan rebels.

Why is there so much animosity between the TPLF and the Ethiopian government?

Until 2018, the TPLF had governed Ethiopia strictly for three decades. During that period Ethiopia’s economy grew steadily, but the party's authoritarian approach eventually prompted a popular uprising. In 2018, Abiy was appointed Prime Minister by the ruling class to dispel tensions.

Abiy immediately set about sapping the TPLF of its national influence once he was in power. He rearranged the ruling coalition of four political parties — founded by the TPLF — into a new “Prosperity Party” — but excluded the TPLF from it.

Ethiopia comprises 10 regions — and two cities — that enjoy significant autonomy, including regional police and militia. Abiy’s push towards a new central party provoked fears that the country's federal system was under threat, and leaders in Tigray withdrew to their mountainous northern heartland.

Tensions came to a head in September last year, when the Tigrayans held regional parliamentary elections that Abiy had delayed due to the pandemic. Abiy said the vote was illegal, and cut TPLF funding, setting off an escalating exchange of offenses. In November 2020, Abiy accused the TPLF of attacking a federal army base outside Tigray's regional capital Mekelle, and using national troops along with soldiers from the neighboring state of Eritrea, launched a military assault.

The story on the ground

Senayt, who's from Mekelle, the capital of Tigray, managed to escape to London in March this year. She is 26 years old. She and her fiancé Chris, 34, have courageously agreed to share their story with KCM. Senayt's English is limited, so Chris described some experiences on her behalf.

Senayt left Mekelle on November 2 for a visa interview in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. It was refused. The next day, the Ethiopian government “unleashed war.” Senayt was unable to contact any of her family in Tigray — including her parents, four sisters, aunts, and a dozen nieces and nephews.

For six weeks, Senayt stayed with her brother, his wife, and their one-year-old son in Addis Ababa. Meanwhile, the Ethiopian army massacred the Tigrayan population.

“Crops were destroyed, farmers were slaughtered,” says Chris. “Children were massacred — 800 people were massacred in [the town of] Aksum, by the Ethiopian and Eritrean forces. And it didn’t reach the media.”

During this time, Senayt and Chris — who were by then in London — were only able to communicate for a few minutes a day by phone. Chris contacted a journalist based in Addis Ababa, but most of what the couple heard came from leaked pictures and videos.

After six weeks, the Ethiopian government took control of Mekelle. The TPLF left for the mountains, because, Chris says, “they didn’t want to fight within and destroy their city.” Senayt was finally able to speak to her family, who told her that their electricity and water had been switched off for six weeks. “They used fire and coals to cook food,” Senayt explains. “I’m not sure about water — maybe from the river.”

Banks were shut, so the price of food skyrocketed.

“I think a lot of people ran to refugee camps in Sudan, just to save themselves,” says Chris. “I stumbled across a picture of Senayt’s road, which I’ve been to many times, and civilians had blockaded it with whatever they could find — rocks, cabinets. The Eritrean troops were driving trucks down the streets, breaking into houses with guns to people’s heads, and stealing everything. I didn't want to tell Senayt.”

Chris contacted a lawyer, who advised him to pursue a global talent visa for Senayt, a world-class contortionist. Senayt flew to London in March 2021.

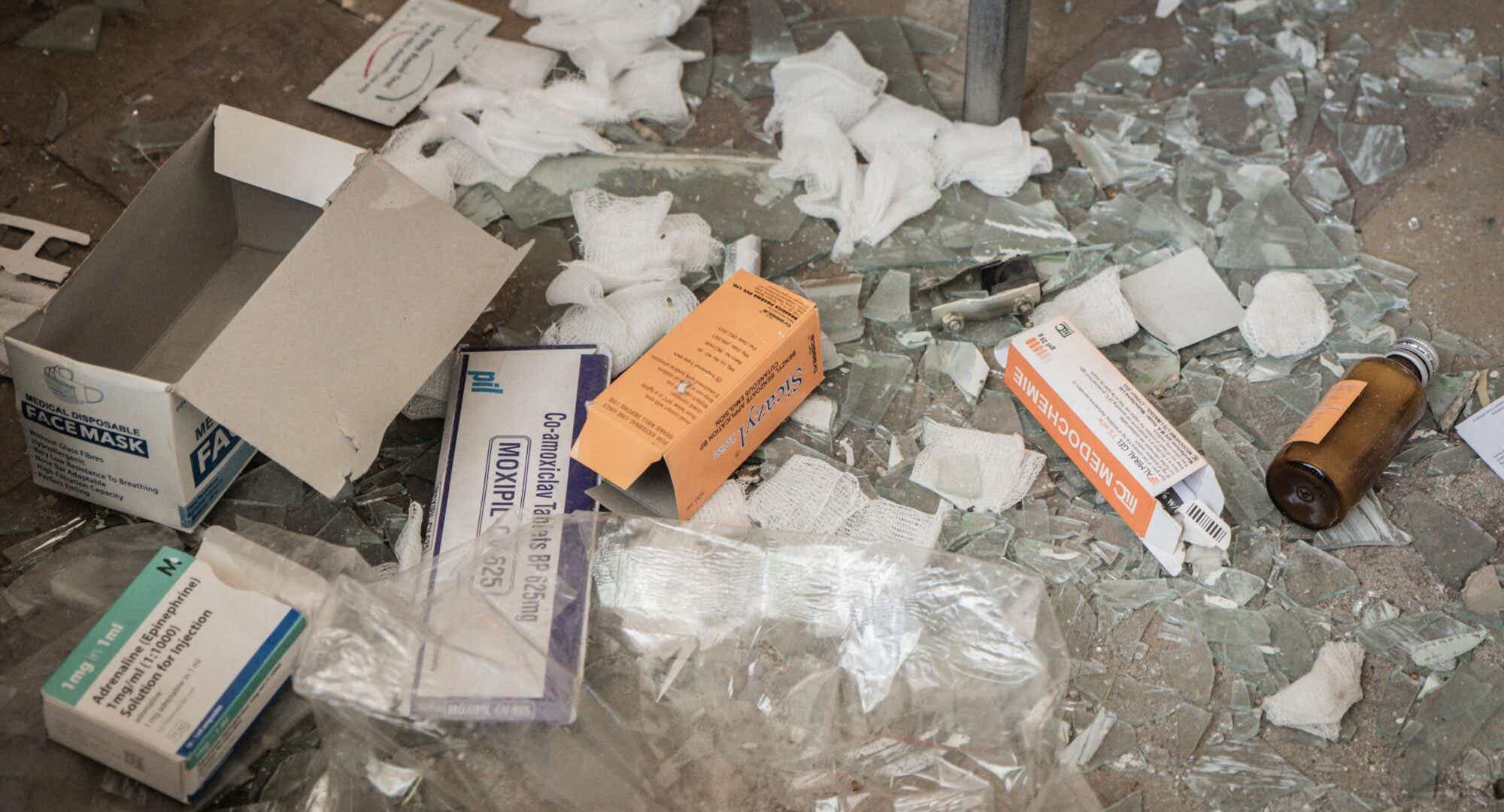

In June, the TPFL retook Mekelle. During this brief respite, Senayt discovered that her father — who's anemic and asthmatic — had been hit by shrapnel in the hospital — even though the Ethiopian government had said that it was only targeting military and government property. “It turned out that they’d been bombing hospitals, schools, thousand-year-old churches, mosques,” explains Chris.

The Ethiopian government turned off all phone communications from Mekelle again on June 7. It also blocked aid. The internet in Tigray has apparently remained entirely shut off since the first assault. “It’s been a total blackout since,” says Chris.

What has the Ethiopian army done in Tigray?

Chris and Senayt’s story is consistent with the media coverage so far. In May 2021, CNN released an exclusive report revealing that Eritrean troops around Tigray were operating with impunity, killing, raping, and blocking aid to starving populations. In some regions, they were acting well beyond their military alliance with the Ethiopian government, waging a “reign of terror.” A horrifying report from March describes troops massacring people in church.

There’s overwhelming evidence that sexual violence is being used as a deliberate weapon of war. In one awful story Senayt and Chris told KCM, a woman was gang-raped, and then her body was filled with stones. She apparently crawled to the hospital and survived. It is likely that many do not.

In May 2021, the United Nations said 5.2 million out of Tigray’s 5.7 million people were in need of food assistance, yet roadblocks set up by Ethiopian and Eritrean forces are still preventing vital supplies from reaching the population.

Ethnic profiling and mass arrests

Increasingly, reports of ethnic profiling and mass arrests in other areas of Ethiopia — such as the capital city of Addis Ababa — are giving credence to accusations that authorities are engaged in a targeted and savage crackdown against ethnic Tigrayan civilians.

“About three weeks ago, we heard that Senayt’s brother had been arrested along with other Tigrayans in Addis, who are being taken to concentration camp-style jails,” says Chris. “There are many stories of these prisoners being executed. Within three or four days, we tried to contact his wife again, but haven’t been able to since. We assume she’s been arrested too, along with their two-year-old son. We’ve now lost contact with every member of Senayt’s family.”

Though the pair remain determined to do all they can to help Senayt's family, the outlook continues to be grave. “The Tigrayan people are very strong-willed, brave people," says Chris. "Every time I’ve been out there they’ve been so loving, so friendly. They don’t deserve this.”