Even though it's been two decades since she was kidnapped from her Utah home in the middle of the night, Elizabeth Smart is still instantly recognizable to millions of Americans who were gripped by her harrowing story.

Smart, who's now 35 years old, has since overcome the traumatic experience to become one of the nation's best-known advocates for missing and exploited children but it wasn't an easy path.

“It's such an isolating moment to have no control over what's happening to your body, whether you live or die, having all choices taken away from you,” she says. “It's hard to believe that anyone else has ever experienced what you've experienced.”

On top of creating the Elizabeth Smart Foundation in 2011, she also teamed up with Portland-based tech company Q5id to launch the revolutionary Guardian mobile app, to help children and adults find their way home. After all, it's a problem that requires a serious solution: More than 600,000 Americans vanish each year, according to The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.

We caught up with Smart to talk about the app, and how she hopes to put an end to all forms of sexual exploitation.

What happened to Elizabeth Smart?

It all started in June 2002, when the then-14-year-old was kidnapped from her bed at knifepoint by a homeless preacher by the name of Brian David Mitchell, who had broken into her family’s home. She went on to spend the next nine months in captivity, during which she endured sexual assault and other atrocities at the hands of Mitchell and his wife, Wanda Barzee. Though Smart was forced by the couple to wear a disguise while out in public, a passerby spotted her after seeing the three walking on a street in the Salt Lake City area, and authorities were able to come to her rescue.

As for her captors, Mitchell is serving two life sentences for kidnapping and unlawful transportation of a minor across state lines to engage in sexual activity. Meanwhile, Barzee was sentenced to 15 years in prison after pleading guilty to kidnapping and unlawfully transporting a minor, but was released in 2018 on the condition that she register as a sex offender.

Where is Elizabeth Smart now?

Now two decades later, Smart is advocating to put an end to all forms of victimization, exploitation, and sexual assault. The statistics are staggering: An American is sexually assaulted every 73 seconds, and for a child, that’s every nine minutes, according to Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

On top of her advocacy work, Smart is a busy mother to her two daughters and son, all of whom are under the age of 10. Understandably, her nightmarish kidnapping has impacted her as a parent.

“It's definitely a struggle for me because I know what can happen,” she tells us. “I know what happens every single day, and being a parent and sending my kids out into the world is scary for me, but I’m doing the best I can.”

Though she tries not to be a "helicopter parent,” Smart believes that educating her kids about the importance of personal safety is crucial. One silver lining is that her advocacy work has helped her bring up hard conversations with her young ones, which she calls a “delicate balance.”

“My youngest is currently four and I don't want to explain in graphic detail what happened to me or what happens to thousands of people all the time,” Smart says. “But I also want her to understand what I'm doing and I want it to be a stepping stone to larger, more intense conversations.”

How Smart's using her experience to save others

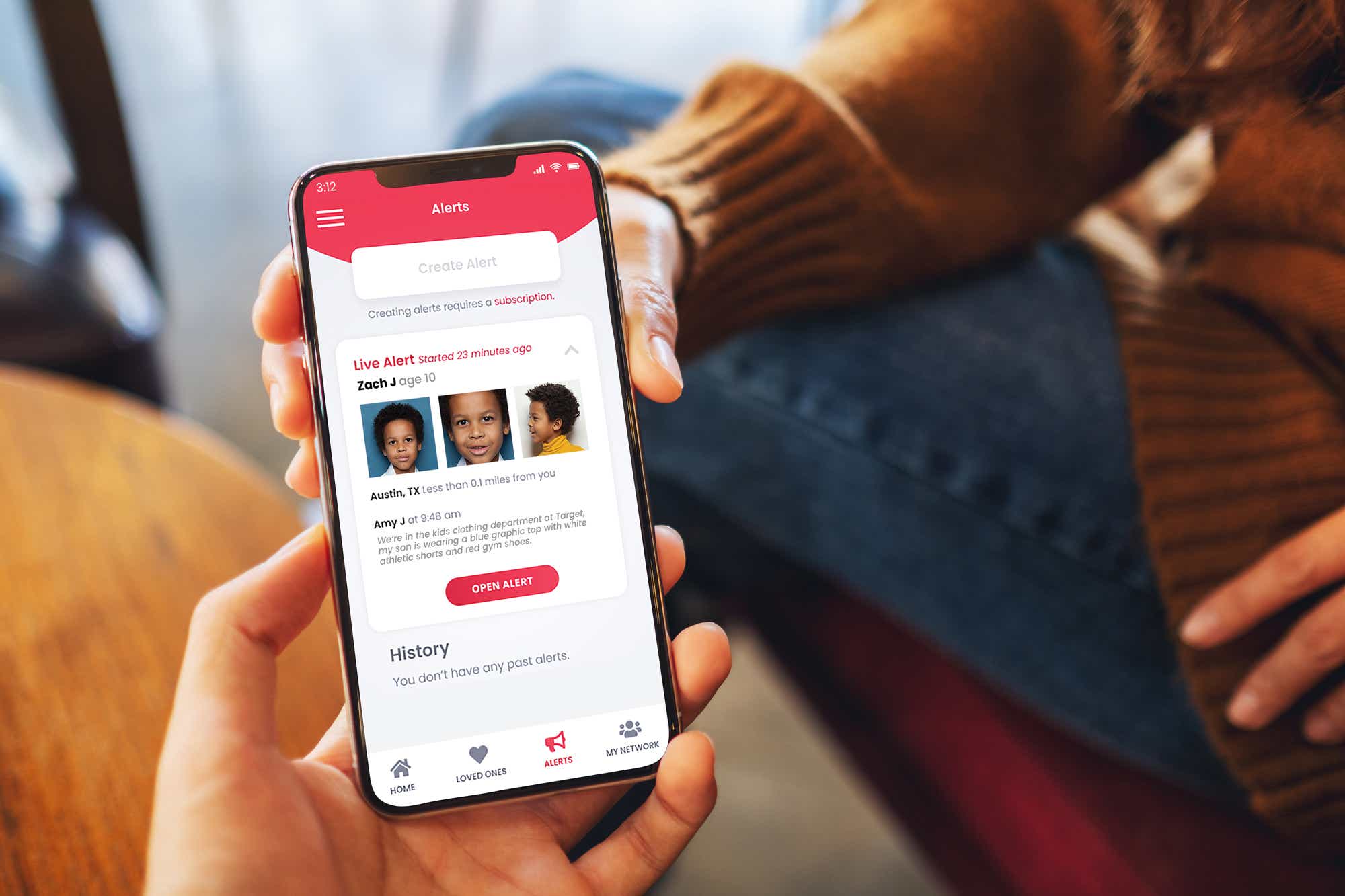

Smart has become a spokesperson for the Q5id Guardian app, which allows users to create a report on their child or elderly loved one the second they go missing.

“Every minute counts when a child disappears: the first 48 hours are absolutely crucial to the safe return of children,” she says. “After 48 hours, the chances of them being found drop drastically.”

It works by sending highly localized alerts to people in the immediate area using a virtual perimeter known as “geofencing" (only app users are notified). The app is free to download — users who want an increased layer of protection can pay $3.99 per month to create profiles of their loved ones. What makes this different from the standard Amber alert is that it helps families provide more specific details about their missing person, including additional photographs. Smart says it also keeps sensitive information out of the hands of potential predators through a pre-screening process (all users have to be vetted and verified).

Smart says that those who've been exploited or assaulted need to remember to never blame themselves for what happened — or for what they had to do to make it out of an impossible situation alive. During her captivity, she says she repeatedly asked herself: "Will I survive if I don't do this?” She says that impulse kept her going, even if meant eating food out of the trash.

In addition to the app, the Elizabeth Smart Foundation announced in January that it was joining forces with the Malouf Foundation, a Utah-based nonprofit that similarly fights child sexual exploitation. Much of what the two foundations do is provide education on sexual violence and exploitation, to prevent them from happening in the first place.

One hard reality the foundations have brushed up against is the stark racial disparity in terms of reporting around missing children: According to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, 98 percent of children reported missing are generally located within days, but of those who are not, most are Black. (And according to a 2015 study, while 35% of the children who go missing annually in the U.S. are Black, they represented only 7% of media reports on missing children.) To address this, Smart says the foundations hold a yearly summit and invite people of different ethnicities, including indigenous communities, to come and talk about the difficulties they face in solving missing person cases.

“Every person should have the same right to be brought back home to safety as I did,” she tells us.

How can you help survivors?

Smart says the best way to help survivors is to, first and foremost, believe them. Sadly, chances are you might know someone who has endured some form of sexual violence: About 1 out of every 6 women in the U.S. has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime, compared to about 3 percent of men (or 1 in 33), according to Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

Another important step is to educate yourself. Though Smart says the #MeToo movement helped address some of the stigma around sexual violence, she adds that most of us are taught what to do in the event of a fire or earthquake, but few know what to do or say when someone discloses that they’ve been raped or sexually exploited.

These conversations can certainly be tough, but Smart says if you love someone who's experienced sexual violence, there are ways to make a positive impact. Give them space to talk — or simply support them if they choose go to the police, seek counseling, or go public with their experience.

“Seeing other people coming forward and talking without shame goes such a long way in helping other survivors define their confidence and realize This was not my fault, I did not deserve for this to happen,” she says. “They may seek action and report their experience to the police, or simply be to walk into a therapist's office and say, ‘I need some help, can you please help me?’ Either of those actions are equally courageous.”