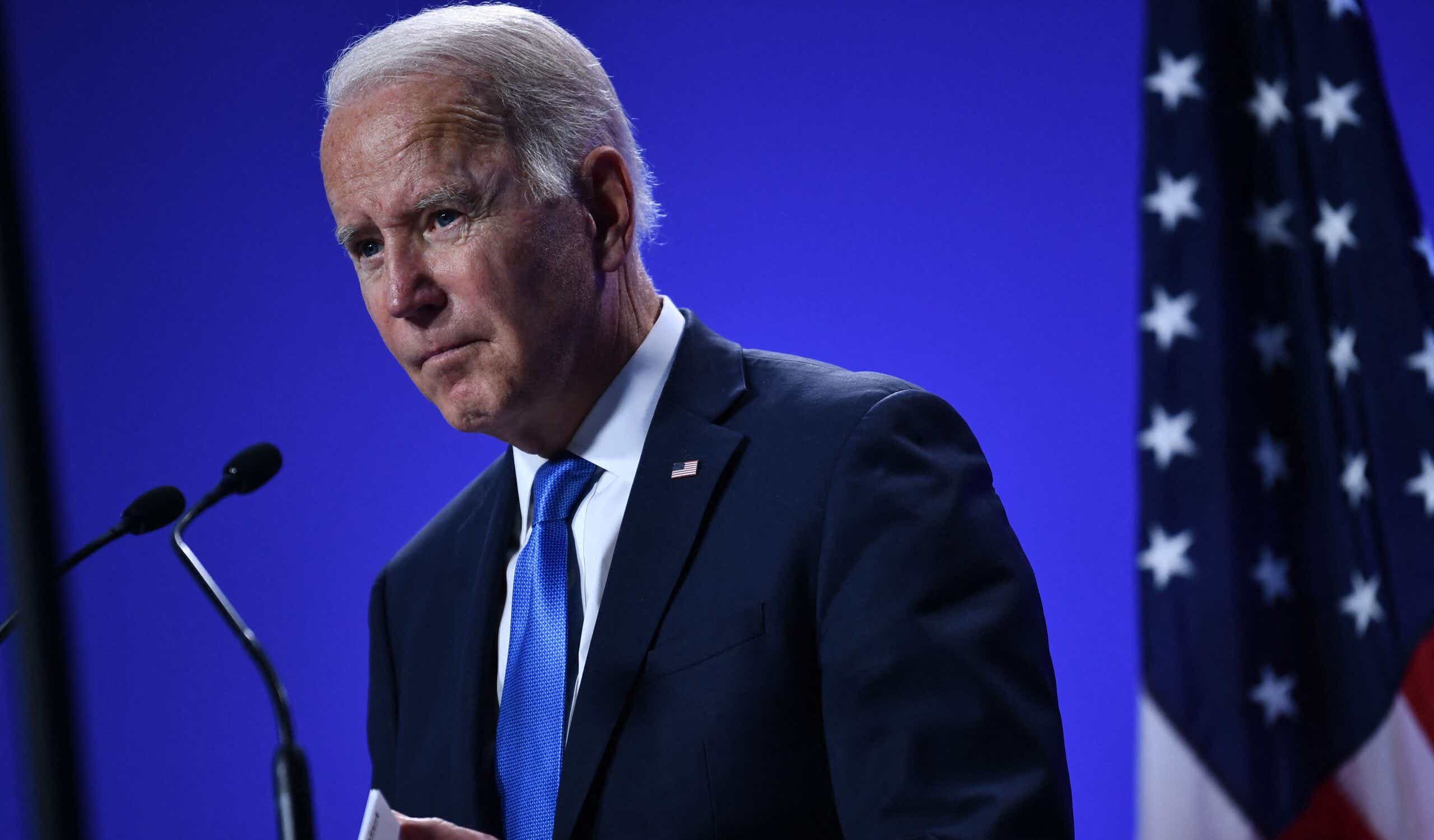

“No democracy is perfect, and no democracy is ever final,” said President Biden on September 15, the International Day of Democracy. “Every gain made, every barrier broken, is the result of determined, unceasing work.”

The President plans to commence some of this work on December 9-10, when he'll host the first of two Summits for Democracy. These aim to bring together international leaders from government, civil society, and the private sector to “set out an affirmative agenda for democratic renewal,” and to “tackle the greatest threats faced by democracies today through collective action.” The hope is to reconvene again next year, when attendees will report back on their progress.

It's a noble idea, but the reality is a little more complicated. We’ve broken down some of the reasons why with the help of Professor Jim Goldgeier and political advisor Rina Shah.

Does the U.S. have the democratic credibility to host such a summit?

“We had an insurrection on January 6, and the losing 2020 presidential candidate continues to insist with no evidence whatsoever that somehow the election was stolen from him,” explains Goldgeier. “We have GOP leaders in various states passing legislation that would attempt to make it harder for certain groups to vote.”

Add to that this week's furor over Texas's new electoral maps, which the Department of Justice says violate the Voting Rights Act, and former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows stalling the Jan. 6 Committee's investigation, and it's not a great look. That being said, if the U.S. walked away from the leadership of the free world, that could be characterized as the country shirking its responsibilities.

"If we do, I can guarantee — as a daughter of immigrants who suffered under [Ugandan] dictator Idi Amin — we won’t like what fills the void," says Shah.

Won't the summit potentially increase tensions between those invited and those not invited?

There’s a real chance that the list of attendees will be interpreted more as a U.S. political statement than a reflection of democratic values — but that doesn't necessarily mean that some exclusions aren't warranted.

"Right now, authoritarian countries have, for all intents and purposes, managed to hijack international institutions," explains Shah. "Look no further than the UN Human Rights Council, which is arguably the world’s most important organization to defend human rights, yet counts among its members Cuba, Venezuela, China, and Russia... How can it achieve its mission when some of the worst offenders are the ones sitting in judgment?"

By including (with notable exceptions like the Philippines and Pakistan) only countries which are truly democratic, Shah argues that the Biden administration is increasing the likelihood that the summit will be able to defend freedom on the world stage.

Are there any non-attendees we should keep an eye on?

“There are two non-invited groups of countries in particular that the administration has an interest in watching,” says Goldgeier. “One is the formal allies of the United States" Hungary and Turkey are both NATO members, but the authoritarian turn by their leaders meant the administration didn't include them... Still, Turkey is strategically important, and so the administration needs to find ways to manage that difficult relationship.”

The second non-invited group to watch is the authoritarian states complaining that the summit is taking place at all — Russia and China.

“It's fine that they're annoyed by a summit emphasizing democracy,” says Goldgeier. “But the United States does need to work with those two countries on issues like climate change, nuclear non-proliferation, and future pandemics.”

So… democracy isn’t always the most useful metric for choosing your allies?

Not always. Unlike during the Cold War, when many of America's allies feared being invaded by the Soviet Union, other countries aren’t necessarily eager to be forced into an “us or them” decision. With authoritarian states like China so heavily integrated into the global economy, countries are prepared to go to some lengths to maintain civil relations — in spite of their serious shortcomings.

“Historically, democratic countries like France, the UK, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Australia and others have been America's best allies,” says Goldgeier. “But the administration recognizes that many countries don't want to be put in a position of having to choose between the U.S. and China as they pursue their own foreign policies."

Put bluntly, both democracies and autocracies can have shared interests. So the division of the world along democratic lines isn't quite as simple — or necessarily as useful — as the summit's mission statement suggests.

Which countries will get special treatment — or instructions — at the summit?

“Poland is a particularly interesting case,” says Goldgeier. “It’s an important ally, and it needs U.S. support right now given the weaponization of migration by Belarusian president Lukashenko, and the Russian military buildup on the border with Ukraine.” (For more on that, take a look here.)

Plus, as Goldgeier notes, Poland has in recent years undermined media freedoms and judicial independence. “So,” he adds, “the United States needs to convey messages of support for Poland's external situation, while also making clear that domestic restrictions in Poland will have a negative effect on the relationship.”

Is there any benefit to Biden holding this summit at such a tough time for America's own democracy?

"Absolutely," says Shah. "It offers a strong example for the world and even for American citizens — that our democracy can still be a force for good and that we are still capable of leading. This is an important message at a time when many of my fellow citizens have lost faith in American examples."

Even so, the White House needs to make clear what it'll do to strengthen our own democracy, given the efforts from some factions within the country to undermine it.

“It'd be great for the American people to hear concrete proposals from the White House regarding the plans for combating the efforts to undermine American democracy,” says Goldgeier.

But will those proposals be effective? We'll have to wait to see until next year...

Jim Goldgeier is a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor of international relations at American University. For more expert insight on the summit, check out his deep dive alongside Bruce Jentleson in Politico.

Rina Shah is an advisor to Renew Democracy Initiative and on a coalition of Republicans & Independents for McAuliffe. She's a DC-based political advisor, commentator, and social entrepreneur. In 2016, she led the #NeverTrump movement, becoming the first RNC delegate to speak out against candidate Donald Trump.