Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the lives of thousands of Japanese Americans took a drastic turn. They were forced to leave their homes, close their businesses and relocate to internment camps in remote stretches of the country. But many young Japanese-American men were also confronted with another dilemma: fighting for a country that deemed them enemy aliens.

Many were eager to serve, and some saw it as the only way to prove themselves in a country that had suddenly turned its back on them and directly questioned their loyalty, writes Daniel James Brown in his new book, Facing the Mountain.

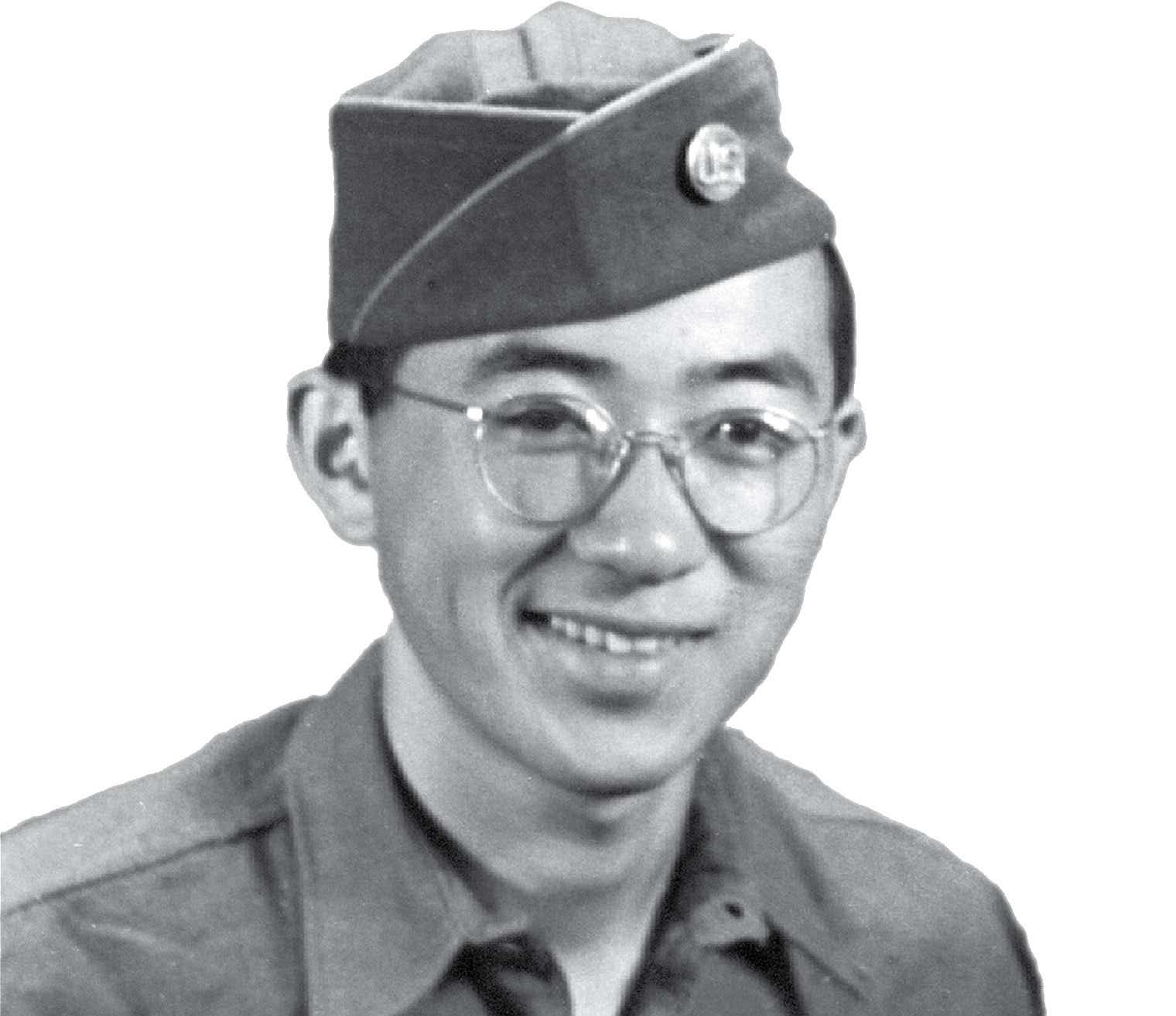

Brown captures that conflict and the emotional struggle of fighting on two fronts — against the enemy abroad and racial prejudice at home — in his book about the 442nd infantry regiment. The segregated unit was composed entirely of Nisei (second-generation Japanese American) men and became the most decorated military unit for its size and length of service in American history. It may be best known for its rescue of the Lost Battalion, in which the 442nd saved some 200 Texans while incurring hundreds of casualties.

For the book, Brown told us he dug into hundreds of hours of oral history recordings provided by Densho, an organization preserving accounts of the Japanese-American internment. The result is a tale of American heroism, and a wonderfully insightful look into the lives of these Nisei men as they ponder identity and patriotism on the front lines.

Read our conversation with Brown below.

Katie Couric Media: Were you familiar with the 442nd regiment before you began writing this book? And what made you want to tell their story?

Brown: No, I had actually never heard of the 442nd. In 2015, I met a gentleman named Tom Ikeda in Seattle. For the past 25 years, he has been video recording and archiving the oral histories of Japanese Americans, mostly from the World War II era. I went home and started listening to a lot of these recordings and there were just a lot of amazing stories in there. That really got me started.

I’m a person that’s very drawn to story, and these were the kinds of stories I like. These were ordinary, young American men and women and their families trying to overcome a really difficult situation following the attack on Pearl Harbor. The book basically grew out of that.

Facing the Mountain focuses on the stories of four men in particular. Can you discuss why you chose them?

I was looking for people whose stories engaged me. And I came to realize that young Nisei men of draft age, they all faced this enormous dilemma. They and their families were being incarcerated on the mainland. Their families were having to sell off their possessions for pennies on the dollar, they were having to shutter their businesses, walk away from their schools and their lives and go to these bleak camps out in the desert.

But at the same time, a lot of these young men, like other young men, wanted to serve their country and wanted to sign up, but they weren’t allowed to simply because of their ancestry until a year later when the Roosevelt Administration reversed course and created the 442nd.

So I focused on the dilemma young men of that age faced and I came up with four people, three of whom signed up for the 442nd and one, Gordon Hirabayashi, who was a resistor. And I thought it was really important to have that part of the story woven in, because many young Japanese-American men did not think it was the right thing to do to sign up and work with the government that had incarcerated them and their families.

Tell us about your process. How much time did you spend going through archival material and conducting interviews?

I listened to hundreds of these oral histories and it took a long time to narrow it down to the four whose stories I thought I could weave together effectively. Only one of them, Fred Shiosaki, was still alive. He was living in a retirement home in Seattle, and his son Michael helped facilitate a lot of really good conversations there, and that was enormously helpful. For the others, fortunately, I had this trove of videotaped oral histories, most of them at Densho and some at the University of Hawaii.

And then I spent a lot of time with family members, getting to know their fathers or grandfathers. And of course, just quite a bit of traditional research. I was at the University of Hawaii library digging through letters and photographs and written histories these guys left behind, and at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. So it was a long process. I worked for five years on this book.

A good chunk of the book looks at what life was like for Japanese Americans in the internment camps. What was it like to write about that experience?

I grew up in California, so I knew about the camps. I knew some basic facts about them, but it was certainly eye opening for me to hear firsthand accounts of just how Spartan the living conditions were and how traumatic it was to have their lives disrupted in that fundamental way.

Also, it was interesting to read about how communities came together within the camps, and how they did what they could to turn the barracks into homes. There were a lot of touching moments of people working together. There were a lot of conflicts and sources of tension too, primarily amongst young men over the issue of whether or not to enlist in the military. That was a huge schism that arose.

Your accounts of the 442nd’s missions in Europe are incredibly detailed. How were you able to recreate those scenes?

In terms of the ones in Italy, I visited those battlefields to get a sense of the countryside. When you do that, you gather a lot of sensory details that help enrich a scene. But mostly, again through the archives at Densho, for a particular battle or scene I had my own protagonists I had his account of what had happened. By searching diligently through these I was able to find other people who were, for instance, with Fred Shiosaki or Rudy Tokiwa, in that battle right there with them. And so through their eyes, I could also gather additional details about what Fred and Rudy themselves went through.

The 442nd became one of the most decorated units in military history. What was life like for the men who returned home after the war?

Even the guys who came back in uniform as war heroes, for the most part, they came back and not much had changed. Fred Shiosaki came back to Spokane, tried to go back to school and integrate back into his way of life, and by and large faced the same kind of discrimination that he had faced before the war. That happened to a lot of these families. When they came out of the camps, they came back trying to rebuild their homes or rebuild their businesses in California or Washington or wherever, and it was pretty much the same situation they faced before the war, despite what the 442nd had done.

It was a little different in Hawaii. When they left Hawaii, the islands were basically one big sugar cane plantation, and very racially stratified. A lot of the 442nd guys from Hawaii came back determined to change Hawaii. They used the GI bill to go to college and then a lot of them went to law school.

This interview has been edited and condensed.