A perplexing trend is unfolding within corporate America. As Simone Stolzoff writes in his new book, The Good Enough Job, “Throughout history, wealth has been inversely correlated with how many hours people work” — meaning that the 1 percenters, those with second homes in the Hamptons and a third in Aspen, have traditionally worked less than the rest of us, because, well, they could afford to. But over the past half-century, something switched.

The richest Americans are now working a hell of a lot more than they used to. Why? It’s complicated, but one crucial factor is that our attitudes toward work have shifted, Stolzoff says. Two hundred years ago, when most Americans were farmers (as were their parents and grandparents) the concept of a “dream job” seemed absurd. “When work was dirty, less was more,” Stolzoff writes, quoting the sociologist Jamie K. McCallum. “Now that it’s meaningful, more is better.”

As kids, we’re told to follow our passion — that “if you love your job, you’ll never work a day in your life.” But is our devotion to labor making us miserable? Stolzoff suspects so. We spoke to the writer about the rise of “workism,” the danger of deriving meaning from your gig, how certain jobs trap us in the rat race, and why, when it comes to work at least, it might be better to settle for “good enough.”

Katie Couric Media: You highlight an interesting phenomenon: In the last half century, Americans, particularly white-collar employees, are working more. Why is that?

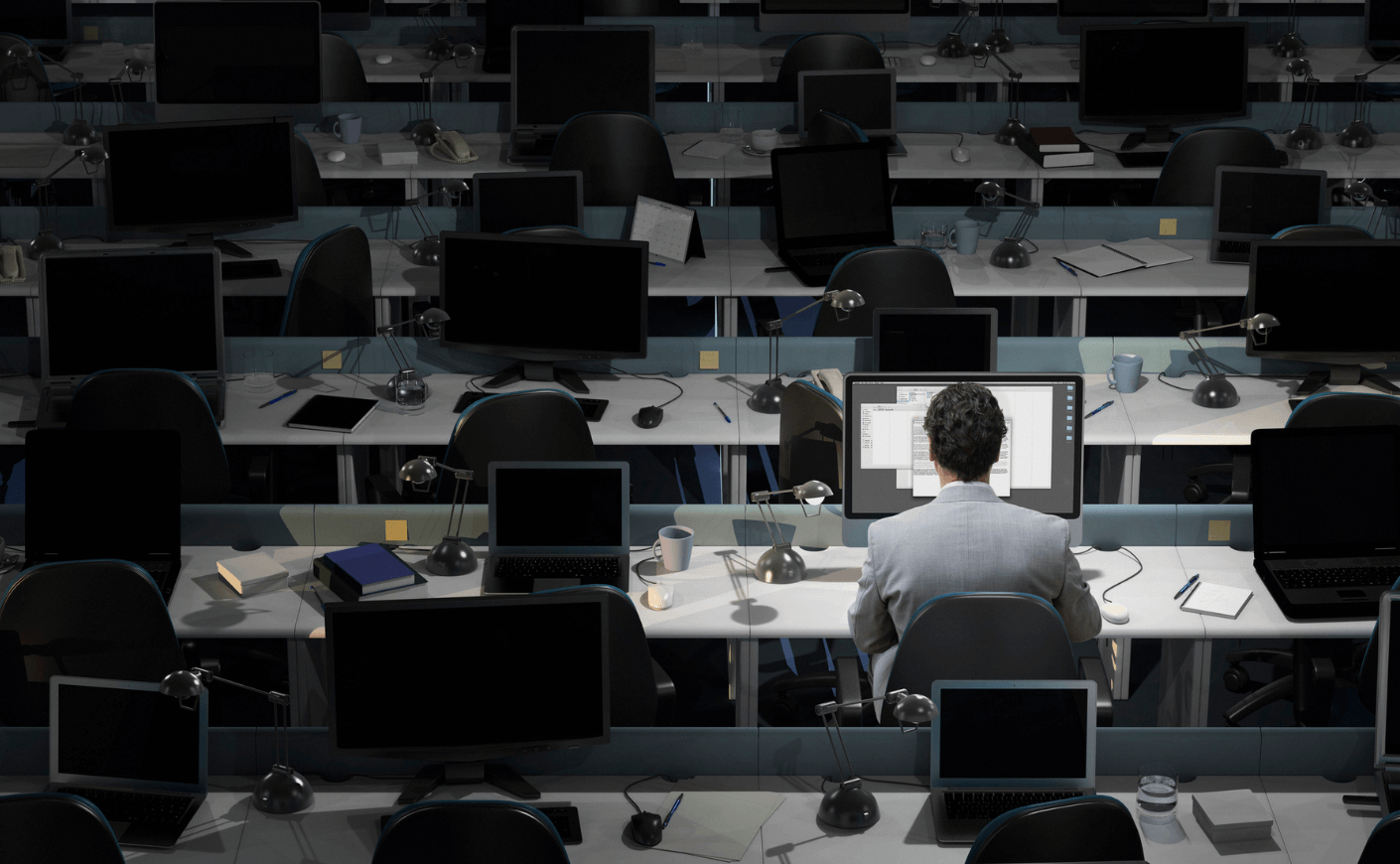

Simone Stolzoff: There are many ways we got here, but I think the biggest one is that in the last 30 or so years, there’s been a decline in other sources of community, identity, and purpose, specifically for Americans — things like organized religion and neighborhood and community groups. So many workers have turned to the place where they spend the majority of their time to get that sense of belonging that they crave. Especially for white-collar, college-educated workers, work has come to be their primary source of meaning and identity. On one hand, that can drive people to find a lot of fulfillment in their work, but on the other hand, can drive people to work more than ever.

So many Americans are staying at the office later, which is ahistorical as you mentioned. In the mid-70s, the average American, average French, and average German worker all worked about the same number of hours per year. Now, the average American works about 30 percent more.

And this is the concept of “workism” that you describe in the book?

Yes, workism was originally coined by journalist Derek Thompson, and it’s the idea that work can be akin to a religious identity — not just something that you look to for a paycheck, but also for transcendence, meaning, and as a means of self-actualization.

One of the perils you talk about is this idea of enmeshment — where your identity becomes enmeshed with your career. Why do you think so many of us have fallen victim to that idea, and how do you think it impacts our sense of wellbeing?

I think one primary reason is that people are parading around their professional accomplishments for others to see. That happens on social media, where the line between the personal and professional is quickly blurring as people build their personal brands. And as I mentioned earlier, with the decline of other sources of meaning or fulfillment, people are increasingly tethering their self-worth to their work.

I think the risks are pretty straightforward. For one, as many people found out during the pandemic, if your job is your identity and you lose your job, what’s left? It’s also just an unreasonable expectation to think of work as something that can always be perfect or a “dream”; it’s not something that our jobs are designed to bear. And then the third thing is that when our jobs are at the center of our existence and everything else gets pushed to the margins, we can neglect other parts of who we are. We’re not just workers: we’re also friends and siblings and parents and neighbors and citizens. And unless we take a more active role in investing in those other parts of who we are, those aspects can wither.

Lots of companies like to say that they’re not just a business, they’re “a family.” You write that that can be a red flag.

First and foremost, even if a workplace could be like a family, I’m not sure that’s something we should aspire to: Most of the families I know are pretty dysfunctional. But I think it’s important to keep in mind the differences between a family, where the expectation is unconditional love, and a workplace, where employment by its very nature is conditional. This sort of rhetoric can be used to bring people in or push people to stay at the office late. But as we’ve seen recently, a company’s loyalty to its bottom line will always trump a company’s loyalty to its people.

Right now, we’re seeing some of these employers who’ve been heralded as community hubs and who offer their employees dinner, and gyms, and the promise of changing the world. It sounds great. Then the market takes a turn and they’re letting go of thousands of their “family members.”

You warn that teaching kids to “chase their passion” or “find their dream job” may not be great advice. Why is that?

A professor at the University of Michigan named Erin Cech says that when we tell everyone that they can do what they love, it can actually exacerbate inequality, because the accessibility to paid work that people are passionate about isn’t equally available to everyone. For example, in journalism, a lot of the entry-level positions don’t pay a living wage. So the people who can afford to follow their passion are often people that have the privilege to be able to weather the inherent risk of doing so.

There’s an institutional side to this too. There are certain industries like teaching or healthcare or the nonprofit sector where people pursue that line of work because they’re passionate about it. And we’ll say things like, “No one gets into this job for the money.” It obscures a lot of the injustices that exist within some of these fields. This was on display during the pandemic, where on one hand, we’re lauding nurses and saying they’re essential workers, but then rarely giving them additional compensation or protections commensurate with the severity of the work they’re doing. So in my mind, the problem of framing work as a labor of love is that it can cover up some of these structural injustices, because we assume that workers are willing to put up with these shortcomings.

The idea of “value capture” — and how it shapes our expectations for our working lives — is something you discuss in the book. What is it, and how does it suck people into the rat race?

Any worker who’s pursuing what the market values without considering what they themselves value is demonstrating value capture. The result is that many people find themselves climbing a career ladder that they don’t actually want to be on, or playing a game that they don’t actually have an interest in winning. You see it begin in our education system, where the ways in which you advance are very legible: You’re told to make good grades and if you do so, you’ll have a good GPA and then you’ll be able to get into a good college. I think these corporations carry on with that level of legibility that can be very seductive to workers. They say, “You can come here as an intern and we’ll train you, and then you can become an analyst, then from there you can become a manager and then a VP, then director.” And that keeps people tied to these jobs, because they continue to advance in the way that’s in the best interest of the company. But we can find ourselves chasing carrots and never feeling full.

I don’t think there’s necessarily a risk in being part of a corporate culture that has a clear hierarchy, as long as you’re clearheaded about the game that you’re playing. I think it becomes problematic when people become enraptured by the incentive of the company to the point where they’re not thinking critically about whether it’s what they want.

So many of us have internalized the current hustle culture. How do we begin to untangle ourselves from that?

What I’ve found is that rather than just making a mindset shift and telling yourself, I need to work less or I should separate my self-worth from my work, it’s more effective to start caring about other things. When you’re invested in other parts of who you are, there’s a natural rebalancing of the equation. I found this myself while writing this book: I left my full-time job and started freelancing. And as many entrepreneurs understand, I became my own worst manager. I was the one cracking the whip, because I’d internalized a lot of the capitalistic and hustle structures around me.

Changing that took the understanding that unless I create some boundaries about when I work or how long I work, work can continue to expand like a gas filling up unoccupied space. I think it’s important to recognize that rest or leisure isn’t the opposite of work. It’s an integral part of our ability to be productive over the long term. There’s data that shows that when people are more rested, they’re more creative, they’re able to maintain a level of output over a longer period of time, and they don’t burn out. Maybe in the short term, if you have a very intense culture and people are working 60 to 70 hours a week, you can see some short-term results. But if you want to attract the best employees and keep them working at their best, it’s important to understand that there has to be space in their lives for things other than work.

Do you think the pandemic has pushed more people to start reconsidering their relationships with work?

I think it was a wake-up call for a lot of people. Everyone’s job changed to a certain extent over the last three years. I think people both learned about the precarity of treating work as their sole source of identity, and many were able to live a more balanced life. For example, lots of us got another hour and a half to spend quality time with our children or have a leisurely lunch because we weren’t commuting. It’s hard to put the cat back in the bag; people are understanding that there are many different ways to design a working life. And rather than starting with the job as the center around which the rest of their lives orbits, they can instead start with a vision of their version of what a life well-lived looks like — and how a job can support that.

One of my favorite things about the framework of the “good enough job” is that it’s subjective. You get to choose what good enough means to you. Maybe it’s a job that pays a certain amount of money or a job that’s in a certain industry, or has a certain title. Or maybe it’s a job that gets off at 3pm, so you can pick up your kid from school. I just hope that whenever you’ve achieved your level of “enough,” you can recognize it. Then convert some of that energy into your life outside of the office.