Picture it: Having a three-day weekend every week. It may sound farfetched, but way back in 1956, Richard Nixon predicted that a four-day work week would be the norm in the U.S. in the “not too distant future.” And in the six-plus decades since, economists and activists have continued to promise that a shorter work week was just around the corner.

Is the 32-hour week just a pipe dream? A growing number of experts insist it’s not — and some think the pandemic has created the momentum needed to push the concept into the mainstream.

In recent years, some companies have been toying with the idea: Microsoft ran a trial of the four-day work week in 2019 at its subsidiary in Japan. The crowdfunding platform Kickstarter said it will implement a four-day work week in 2022, and Unilever is testing out the concept in its New Zealand office.

Entire countries are warming to it, too: Spain said this spring it would run a trial of the four-day work week, New Zealand’s prime minister has recently floated the idea, and in Iceland a pilot program that ran from 2015 to 2019 has been deemed an “overwhelming success.” The authors of the study in Iceland, which was released last month, found employers had streamlined their operations by shortening meetings and cutting out unnecessary tasks, while employees remained highly productive and felt more energized and less stressed.

In the U.S., a California Congressman just last month introduced a bill to lower the standard work week to 32 hours.

“Now more than ever, people continue to work longer hours while their pay remains stagnant,” Rep. Mark Takano said in a news release. “We cannot accept this as our reality.”

The benefits of a four-day work week

The upsides have been studied fairly extensively. A shorter work week (of course) boosts employee satisfaction, with employees reporting improved work-life balance. But trials have also shown that it raises productivity. Microsoft said that during its experiment in Japan, output rose by 40% while the branch also cut electricity costs by 23%.

“You have a far more efficient and far more productive workplace that people like coming to,” Charlotte Lockhart, the head of advocacy group 4 Day Week Global, told us.

In 2018, Lockhart helped launch a four-day week at the New Zealand firm Perpetual Guardian. Since then, the company has reported higher retention rates and strong interest from young candidates. For that reason, the four-day week is being eyed as a way for smaller companies to lure top talent away from bigger firms that can offer higher salaries or pay for perks like employee gym memberships or tuition reimbursement, Lockhart said.

Is this the solution for preventing burnout?

The four-day week has gained momentum as more Gen Zers enter the workforce, Lockhart says. “They don’t want to work ridiculous hours. They’ve seen the impact that’s had on their parents.”

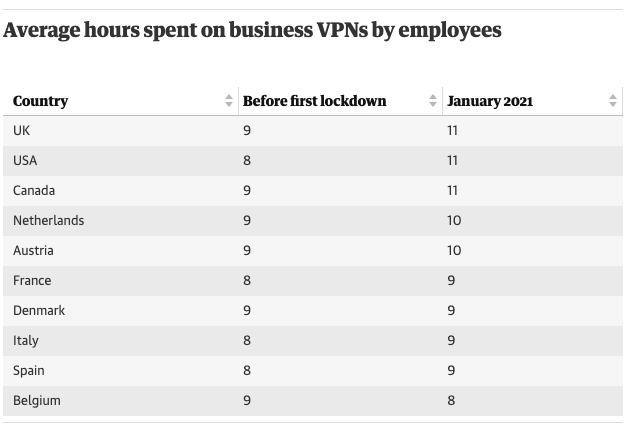

Tools like email and Slack have practically obliterated the traditional 9-to-5 workday in many sectors, giving us the capability to work at any hour of the day, not just when we’ve clocked in at the office. It’s these technological advances that led Nixon to believe 50 years ago that we’d be working considerably less, when the hours we spend laboring are actually creeping up. And workplaces haven’t adjusted, contributing to a steep rise in employee burnout. The issue only became worse during the pandemic.

“There’s a recognition of the way that work has just taken over our lives — and not in the right proportion,” Lockhart said.

But given the past year, when corporations were forced to completely reimagine their workflow, more companies are starting to consider a shortened work week as a serious option. Lockhart says that before Covid-19 shut down offices, the concern she heard most often from the C-suite about giving the four-day week a shot was a “lack of trust” in their workforce to be productive and meet certain standards even when they’re away from the gaze of their managers.

The pandemic proved employees could be trusted while working remotely, Lockhart says. It’s also pushed people to prioritize flexibility in their work and demand it from their workplaces, making the four-day week even more alluring.

Could this really happen in the U.S.?

Lockhart acknowledges that especially in the U.S., where we’ve traditionally venerated long hours and hard work, companies may be more resistant to adopting a four-day week than in parts of Europe where work-life balance is prized. But she believes this change is coming stateside sooner or later, because businesses will realize the economic benefits they can reap, will want to get ahead of the curve, or finally understand that it can fundamentally make their workers’ lives better.

“We’re not saying that you shouldn’t work hard,” Lockhart said. “We’re just saying that you should work appropriately — and that is productive.”