For decades, U.S. states have fought male violence against spouses and partners on two fronts: with mandatory arrests and prosecutions, and through programs focused on reeducating men about their attitudes toward women.

Yet for nearly as long, researchers have gathered evidence that these strategies don’t work.

Instead, studies suggest that less punitive and more therapeutic tactics can better reduce repeated violence. In recent years, this has prompted some government agencies to change direction. Some leading domestic violence activists and researchers want to see that happen faster.

“We’ve simply got to have new approaches and new paradigms, because we haven’t done a very good job with all the stuff we’ve been doing,” says Jacquelyn Campbell, a professor of nursing at Johns Hopkins University and a national leader in research and advocacy related to domestic and intimate partner violence. “It’s 2025 — don’t we know more about human behavior and how brains work than we did in the 1990s?”

Perceived lenience toward men who have threatened or hurt women is understandably controversial. Yet momentum is growing for less frequent arrests — or at least more selective ones — and more attention to the emotional wounds and stress that can lead men to violence.

The feminist fight against male assaults

Today’s broad consensus about how to treat men charged with violence against wives and girlfriends began forming in the 1970s. In the decade prior, marital rape still wasn’t considered a crime and police often responded to panicked women’s calls with mild warnings to their spouses. Violence against women by spouses or boyfriends was still vastly underreported, even as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would later report that about 41 percent of U.S. women have experienced sexual or physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetimes.

But then, half a century before #MeToo, second-wave feminists awakened Americans to the plight of women trapped in dangerous relationships. They dramatically improved women’s safety and welfare by empowering them financially — fighting for better access to jobs and reproductive health care — and pushing governments to confront violence against women that, as abundant research shows, is mostly and most lethally committed by men.

In the late 1980s and the 1990s, many state governments adopted versions of a comprehensive strategy to address intimate partner violence, known as the Duluth Model. Developed in the early 1980s by activists in Duluth, Minnesota, it favors ample victims’ services and robust law enforcement, including mandatory arrests when police have probable cause to suspect domestic violence. Duluth Model advocates have also supported pursuing prosecution regardless of the victim’s wishes.

These strategies are also reflected in the Violence Against Women Act, which Congress passed in 1994 and has reauthorized four times. The landmark legislation has distributed more than $11 billion, much of it for victims’ services such as shelters, counseling and a national hotline. Yet some researchers estimate that more than half of the funds have supported training of police and prosecutors to strengthen their response.

The Violence Against Women Act has helped to protect and support millions of survivors, while shining light on a crime once regarded as a private affair. From 1994 to 2010, as states adopted those get-tough policies, reports of intimate partner violence declined by 64 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Yet the hard-hitting strategies have come under fire from scientists and advocates who charge that jailing abusers can exacerbate conditions that lead to violence, such as racism and poverty. “If we were willing to actually look at this as an economic problem, I truly believe we would make a greater dent in the rate of violence than with any other kind of intervention,” says legal scholar Leigh Goodmark of the University of Maryland Carey School of Law, author of a 2022 critique of the Violence Against Women Act inthe Annual Review of Criminology.

Goodmark argues that the decline in reported intimate violence crime was part of an overall drop in crime since 1994. Other researchers attribute factors other than the Violence Against Women Act for that decline, including a steady drop in marriage rates starting in 1970, as well as improvements in women’s economic status and an older and presumably wiser population.

Indeed, a 2020 analysis of 11 published studies concluded that mandatory arrests have failed to stop most abusers from repeating their crimes. Aggressive prosecution may even increase the violence, according to Radha Iyengar Plumb, who in 2009, as a Harvard health policy researcher, reported an analysis of FBI data in the Journal of Public Economics. Plumb found that intimate partner homicides increased by about 60 percent in states with mandatory arrest laws, for reasons, she wrote, that could include victims’ reluctance to call police if it was likely to end in an arrest and batterers taking revenge if they did.

Such findings help to explain why 21 states now allow police more discretion.

Additionally, in recent decades several states and counties have retreated from the second front of America’s war on intimate partner violence: the confrontational programs abusers must attend in an attempt to get them to change their ways.

Power, control, and pushback

Besides its support for robust police involvement, the Duluth Model includes a batterer-intervention curriculum, “Creating a Process of Change for Men Who Batter,” used today throughout the United States and in many other countries, often as a condition of parole. By the late 1990s, many states had begun combining the Duluth curriculum with cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, with the aim of helping abusers recognize and change unhelpful thinking patterns.

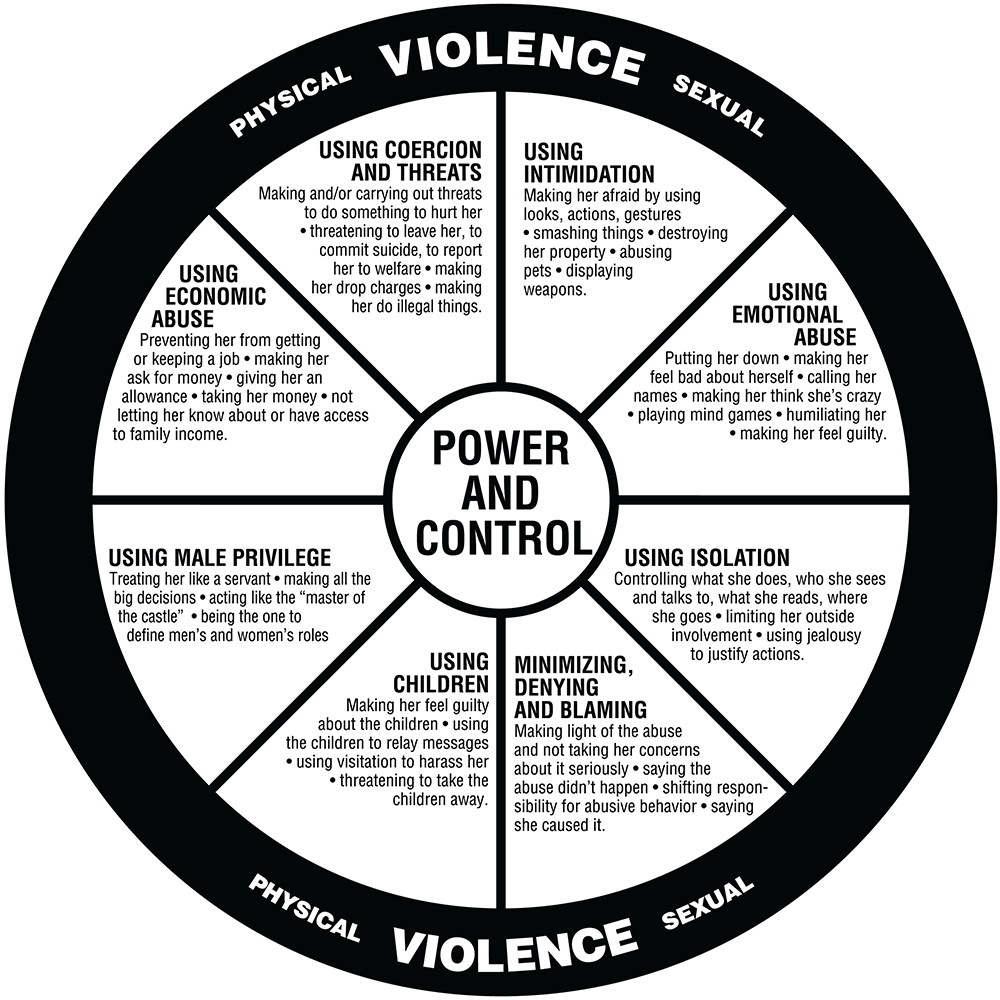

Inspired by now 40-year-old interviews with 200 women survivors of violence, the Duluth curriculum teaches participants that a patriarchal culture encourages men to use violence as a means of “power and control.” In weekly group classes, court-ordered participants study a “power and control wheel” that illustrates controlling tactics such as victim-blaming and using children as weapons.

CREDIT: DOMESTIC ABUSE INTERVENTION PROJECT

Throughout the curriculum’s history, critics, including many scientists, have complained that it scolds and shames men. More important, they say, the Duluth program and others in more limited but also longtime use (including a precursor, Emerge, founded in 1977) have failed to stop abusers from committing new crimes.

Several state and local government agencies around the country have come to share that assessment. In 2014, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy determined that the Duluth curriculum failed to prevent repeated intimate partner violence. Subsequently, the state allowed alternative interventions to be used, according to Rebecca Goodvin, a senior research associate at the institute.

In Iowa and Nebraska, state prison administrators lost so much faith in existing programs like the Duluth curriculum that they ultimately turned to programs more focused on helping men manage their emotions.In California, which has long relied on Duluth-inspired curricula, a state law has allowed six counties to pilot alternative programs with “evidence-based practices.”

These public officials are responding to what researchers have called a tsunami of data challenging the effectiveness of the Duluth curricula. In one of the most frequently cited studies, clinical psychologist Julia Babcock of the University of Houston led a meta-analysis of research, published in 2004, examining commonly used batterer-intervention programs, including the Duluth-plus-CBT approach. She concluded that they had minimal impact on repeat crimes, based on police and partners’ reports.

Twenty years later, in a larger analysis, her conclusion was similarly discouraging.

“You can’t really make a great case for the Duluth Model,” she says.

Sympathy for the devils

Babcock’s news isn’t all bad. Her 2024 analysis includes studies comparing the Duluth-plus-CBT approach with newer alternatives, some of which achieved significantly better results.First in class was a program known as Achieving Change through Value-Based Behavior (ACTV), developed by clinical psychologist Amie Zarling at Iowa State University.

Zarling created ACTV by adapting a more mainstream approach, known as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which combines acceptance and mindfulness techniques. Using input from criminal justice experts and other sources, she incorporated tactics to better meet the needs of men accused of domestic violence. For example, ACTV emphasizes learning to be calm and deliberate, a skill Zarling says is often lacking in such men, likely because many have themselves been traumatized. The majority of those she studies, she says, have had four or more adverse childhood experiences such as physical or sexual abuse, neglect or witnessing violence at home.

Abundant research confirms this link. A 2009 study found that men who had suffered moderate to severe physical abuse in childhood were 3.9 to 4.5 times more likely to use violence against their partners as adults. “They never learned to regulate their emotions, and so many started using substances to deal with those trauma reactions, which just adds to the risk factors for domestic violence,” Zarling says.

As Zarling explains it, the main difference between Duluth-inspired approaches and ACTV, put simply, is that while the former tries to teach men to change their thoughts about their female partners, ACTV aims to help them choose behavior that matches their values, even in the presence of those thoughts. It’s a skill known as “psychological flexibility.”

In 2010, the Iowa Department of Corrections piloted ACTV with men required to complete an intervention program, after determining that the Duluth-inspired approach had failed to significantly reduce intimate partner violence.

This enabled Zarling and colleagues to conduct a large study comparing ACTV with Duluth-plus-CBT, using data from 3,474 men in Iowa who had been arrested for domestic assault and court-ordered to one or the other of the programs, each lasting 24 weeks. After one year, 3.6 percent of the men who had completed the ACTV program had been charged with a new episode of domestic violence,the 2017 study found, versus 7 percent of those who had completed the conventional treatment.

Four years later, researchers from Northwestern University published another study in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology comparing outcomes from ACTV with Duluth-plus-CBT. They looked at 725 men classified as medium or high risk for repeat offenses who were court-mandated to complete a batterer-intervention program with Ramsey County Community Corrections in Minnesota. After five years, 69.6 percent of those enrolled in the Duluth-inspired program had received a new conviction, compared to 34 percent of men in the ACTV program.

While Zarling continues her research, interest in her program is growing. Since 2024, several Nebraska prisons have been offering ACTV to incarcerated individuals, says criminologist Tara Richards of the University of Nebraska Omaha, who collaborates with public agencies to evaluate criminal justice programs.

In recent years, other jurisdictions, including in Vermont and Ramsey County, Minnesota, have also piloted or adopted ACTV for intimate partner offenders.

“They don’t want to be abusive”

Another emerging competitor to the Duluth curriculum is “Strength at Home,” which was adopted throughout the Veterans Administration in 2013. Intimate partner violence is unusually prevalent among military veterans who have experienced trauma, yet before that year few VA hospitals offered more than anger management classes.

Strength at Home is “trauma-informed,” says Casey Taft, who created the program as a staff psychologist at the National Center for PTSD in the VA Boston Healthcare System. It aims to help men understand the impact of their emotional wounds, whether stemming from childhood or combat, in a collaborative, empowering manner.

“Instead of trying to get really confrontational with our clients and force them to change, we treat them with respect and allow them to talk about their experiences in an open way, so that they take ownership over their actions,” says Taft. For the most part, he adds, “Our clients want to change. They don’t want to be abusive; they don’t want to have these problems with violence and anger.”

The U.S. courts’ long reliance on the Duluth curriculum and other interventions that aren’t evidence-based is dangerous, says Taft. “You have violent folks who are hurting or killing their partners and we’re sending them to programs with no demonstrated effectiveness.”

Like most other batterer-intervention programs, Strength at Home requires men to meet weekly in groups in which members, guided by a facilitator, challenge and support each other. “We’d help each other; we’d give advice to each other, like, if that made you mad, how did you handle it? How could you have handled it better?” recalls Ran Stewart, a New York state construction worker who graduated a few years back from a Strength at Home program adapted for civilians. “We ended up being a brotherhood.”

Research support for Strength at Home includes a randomized controlled trial of 135 male veterans and 111 female partners, published in 2016. The veterans were assigned to either Strength at Home or treatment that offered support such as individual therapy, substance abuse programs and counseling for intimate partner violence. After researchers led by Taft interviewed clinicians, the veterans and their partners, the team concluded that Strength at Home was more effective than the enhanced program in reducing physical and psychological violence against partners. Three months after completion of the program, 26.7 percent of the treatment-as-usual participants committed new crimes, compared with 18.5 percent of those who completed Strength at Home.

In 2023, Taft published an additional study, this time including 1,754 participants at 73 VA clinics. It concluded that Strength at Home helped to reduce physical intimate partner violence by 17 percent and psychological intimate partner violence by 23 percent.

Since then, Taft has continued to test his approach on civilians, with support from a $2.8 million grant from the nonprofit Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Initiative, created by the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. He expects to have results in 2030.

“I’m really looking forward to that data,” says Johns Hopkins researcher Campbell, who collaborated with Taft in a recent paper in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, which called for more evidence-based programs for intimate partner violence offenders. “I would like to see Casey’s program in every community in the United States.”

Complexity after complexity

Scott Miller, executive director of Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs, which trains Duluth facilitators, says his nonprofit organization has never subjected the Duluth curriculum to a randomized controlled study. “We’re not scientists,” he says.

Indeed, studying behavior as complicated as intimate partner violence is a major challenge under any circumstances, but especially when done outside of controlled settings such as prisons or VA clinics. Convicted criminals may not show up. Partners may shade the truth for their own reasons. Studies are expensive and time-consuming, and researchers can’t offer no treatment as a comparison in controlled studies, since all participants must receive a program by law.

For the Duluth curriculum, the challenges are even more complex. The intervention was always intended to be part of a larger, coordinated community response, Miller says. “If you pluck our men’s group out of our system that we’ve designed and stick it as a standalone, it’s not going to operate the same way.”

Importantly, too, Duluth classes vary widely state to state and even group to group. Programs can last from 12 to 52 weeks. Group leaders range from experienced psychologists to people with no college experience, according to Miller. They receive three days of online training and a 324-page instruction manual and videos depicting vignettes of abuse, after which all are free to adapt the program.

“We didn’t want to be that prescriptive because we didn’t want to curtail creativity,” Miller says. “We wanted people to use it and figure out different ways of using it.”

Indeed, there’s nothing to stop group leaders from improvising beyond the instruction manual, notes Richards. “They all change it, supplement it, bring in different components, and are responsive to their groups. So it’s like comparing apples to oranges to bananas.” Other intervention programs are vulnerable to the same comparison challenges if facilitators implement them differently, she adds.

Amid all its challenges, the Duluth program has been evolving, says Miller. Over the summer of 2025, mindful of the new research and following a four-year review, Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs rolled out a fourth iteration of the curriculum that incorporated some elements of ACT.

As the field develops, experts say they would like to see more standardization of batterer programs, and more rigorous, independent evaluations of their impact.

Also important, according to Richards, is infusion of more resources so participants do not have to pay out-of-pocket for the programs. With fees of $25 to $75 per class, facilitators often struggle to retain participants who may be jobless or marginally employed. Batterer-intervention programs are, in fact, notorious for their dropout rates, with researchers reporting that up to 67 percent fail to complete them.

Zarling says she hopes that in coming years more researchers will join the field and help to develop new, empirically tested strategies to replace ineffective efforts.

“We are so programmed to hate these men, and there’s certainly some validity in that,” she says. “But what I think people tend to forget is that if we don’t help them, they’re just going to do it again and again.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.