A few sweet weeks of summer remain, but back-to-school is just around the corner, and the time before kids return to class is crucial for facilitating a smooth transition — especially after the way Covid-19 turned learning upside down in 2020.

It’s normal for children to have questions or even worries about getting back into the swing of things after summer vacation, Covid or not. But this transition could be particularly tricky. How parents handle those concerns is an essential part of setting their kids up for success, so we got some expert advice on what to expect as your little ones return to their routine — and how to handle the bumps in the road.

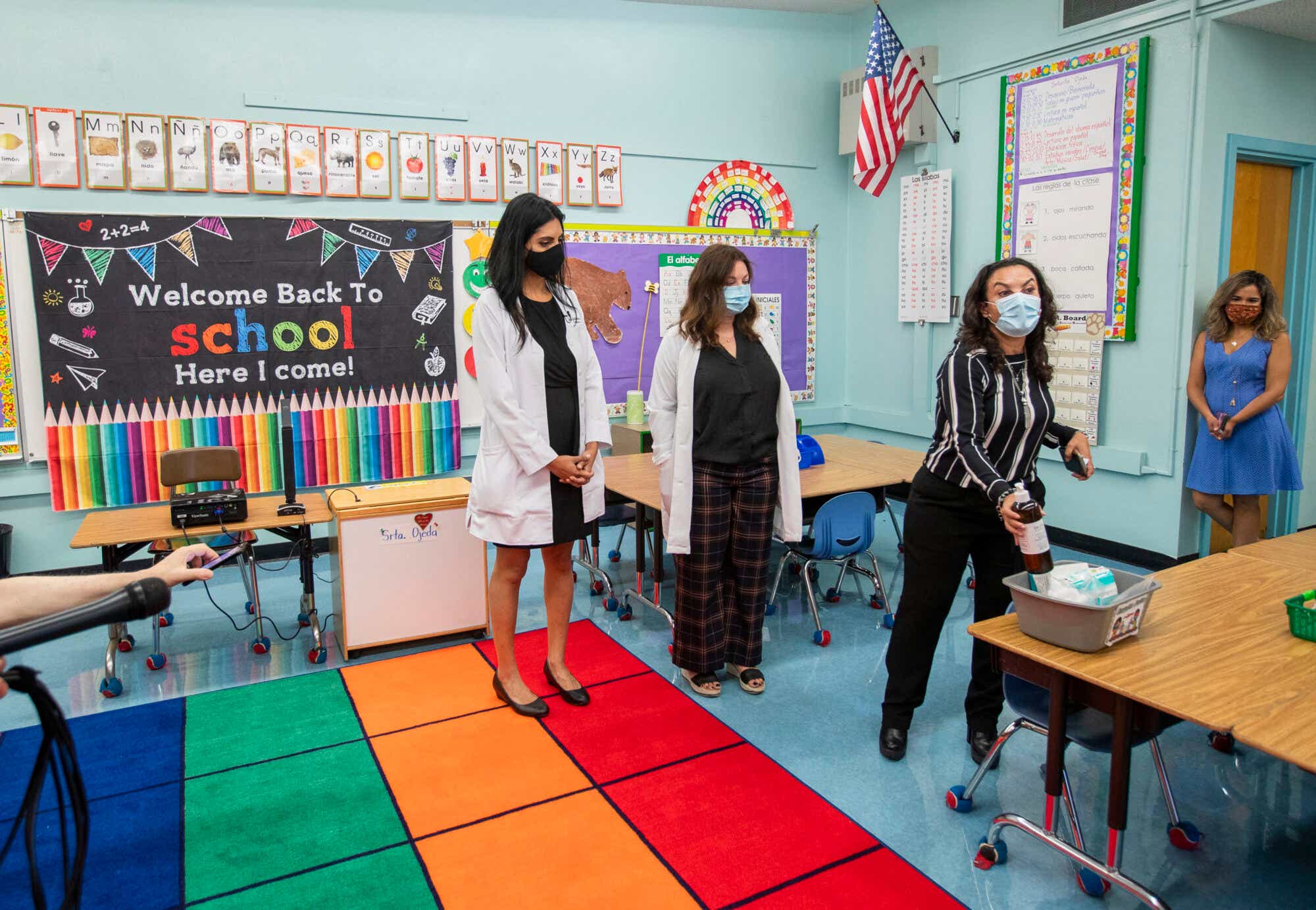

Dr. Fauci wants kids back at school

The situation is changing every day thanks to the highly contagious Delta variant and lagging vaccination rates, but Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, told KCM this week that being back at school — in a healthy way — is the best option for kids.

“It is a very important primary goal in the fall to get the children in class and not virtual because we are well aware of the deleterious effects on children: their development, their mental health, their educational development,” Fauci said.

But Covid-19 is still a factor

Current CDC recommendations say children should ideally return to in-person learning full time, with “layered protection strategies in place.” These include “universal indoor masking” regardless of vaccination status, maintaining physical distance between students, regular hand-washing and classroom disinfection, and keeping kids home when they’re feeling sick.

“There’s always going to be a subset of the child population that has anxiety to begin with, so these types of things just ratchet their anxiety up even higher,” according to Joshua Rosenthal, the president of Manhattan Psychology Group and a clinical psychologist specializing in child, adolescent, and family treatment. “Those kids are going to need to start therapy or resume therapy or make sure their medicine is optimized. But that’s only a subset. Most kids are pretty resilient and flexible when it comes to this stuff.”

While masks in class may be a disappointment for kids who expected to be without them this year, most students will respond well to the structure of school, even with Covid protocols, because everyone is expected to do the same thing. “The social pressure kind of kicks in and it becomes a positive,” Rosenthal said. “This is what everyone’s doing, so it’s not a big deal.” And for teenagers old enough to be vaccinated, this year will offer more flexibility in how they’re able to socialize.

At this point, safety protocols are nothing new, so it’s helpful to draw on your kids’ personal experience, said Susan Groner, a mother, author, and founder of The Parenting Mentor. She suggests reminding them of everyone who’s working to keep them healthy — “the government, your school, people in our community and in our household” — and also reflecting on their own resilience through the pandemic thus far.

“There were a lot of hardships and sadness that came with it, but you did it and your kids did it. Pay attention to that,” she said. “Sit down and have a special meal where you talk about, ‘Wow, look at what we did. Look how we got through this. And if you can do this, the next time something difficult comes along, you’ll know you can get through that as well.’”

Back-to-school nerves are normal

Rosenthal says he sees the same cycle in his practice each August, when stress creeps in as summer activities wrap up and school emails start monopolizing parents’ inboxes. Every child has an individual response, which Rosenthal charts using two metrics: “the anxiety spectrum and the excitement spectrum.” Some kids are at “100 percent excitement,” but there’s plenty of reasons why many exist somewhere in the middle.

“Maybe they didn’t do all their summer reading work, or maybe they have one or two friends, not a ton of friends. Maybe unstructured time at school is hard for them,” Rosenthal said. “Every kid is different, so you have to work with each. And that’s within the family. You might have two or three kids, and they’re all totally different.”

Wherever your child falls, it’s important to meet them where they are and treat these feelings as valid.

“We as parents don’t want our kids to feel nervous, but they have a right to feel anxious and worried about starting school because it is a new experience, and most people, even adults, feel that way before they go to something new,” Groner said.

Help your kids break down negative thoughts and feelings

Broach the topic with open-ended questions that don’t tell your kids how to feel or project your own worries onto them. Instead of, “Are you nervous about starting school?”, kick things off with something neutral, like, “School is coming up soon — what are you thinking about?” Rosenthal recommends listening closely to their responses to sort through thoughts versus feelings.

“‘I’m nervous, I’m sad, I’m excited, I’m angry, I’m frustrated, I’m petrified, I’m panicky’ — those are all feelings,” he explained. “Thoughts are things like, ‘I’m not going to be able to do it, it’s going to be hard, people aren’t going to like me, I’m going to get lost, I’m not going to like my teacher.’ So if you can get them to separate the thoughts and the feelings, then you can start to break it down a bit.”

Identifying negative thoughts is helpful because then you can challenge them in a productive, concrete way. For example, if your child says something like, “The whole day will be terrible,” you can change their thinking by pointing to at least one thing they can look forward to.

“Maybe it’s, ‘I can make you the best lunch you can imagine,’ so they’re looking forward to lunch,” he said. “Or this kid is super athletic and they love gym, but they can’t stand anything else. So let’s think about gym, right? Let’s try to find something to anchor you to get through that transition.”

But what about a kid who really struggles at school?

Some students simply have a hard time at school, whether it’s socially, academically, or otherwise. That makes things complicated, especially after a year when they were able to stay home via remote learning.

For students with special needs, assistance like speech therapy, physical therapy, or counseling is paramount, and it’s essential to keep those support systems in place. Acute attention is important for every kid, whether they require special services or not, but Rosenthal cautions against confusing accommodating their needs with enabling their complaints.

“Accommodating would be if the child has difficulty and you come up with ways they can progress, like anchoring something fun, trying to build up their self-confidence, preparing in advance, building a bridge for them,” Rosenthal said. “Enabling is actually the opposite. It’s a way of helping the child avoid accomplishing the task — letting them stay home, letting them go in late, getting a hybrid schedule for them, or trying to get them out of classes. All of that enables the child to stay in this fixed position of, ‘School is bad, and I don’t need to be there.’”

Getting ahead is key

The morning routine is such an important tone-setter that Groner offers an entire workshop based on optimizing it — and avoiding a morning of rushing and screaming before school even begins.

The weeks leading up to the first day of school are the perfect time to establish a clearly defined (and more peaceful) routine, but that doesn’t mean the final stretch of summer has to be a bummer. Kids can still sleep in, but try timing them once they’re up to establish how early they’ll need to wake on a school day.

“Give them half an hour to get up, get dressed, make their bed, brush their teeth, have breakfast, be packed and ready to go,” Groner said. “Just practice it and see, was that enough time? If you need more time and you don’t want to rush, maybe you get up 15 minutes earlier so you get 45 minutes in the morning. That’s good information.”

The opportunity for practice extends beyond your home. For kids who are nervous about being back to in-person learning, Groner suggests taking steps to refamiliarize them with the environment they’re returning to.

“If your kid hasn’t been at school in a long time, go have a little family picnic at school, or maybe grab a few friends and go play in the playground,” she said. “That’ll spark memories of what it was like when they were there before.”

Anxiety might arise after they start school

While parents should aim to ask specific, targeted questions at the end of the day, you might often get short, vague responses. But that’s fine, Rosenthal says, because “with kids, you tend to go more by behavior and less by what they say.”

Look for the following once school is in full swing: Do nighttime worries about school interfere with their sleep? Do they drag in the morning to avoid arriving on time? Do they invent “somatic complaints,” like a headache or a stomachache, to try and stay home (and then miraculously become healed by the weekend)? Are they staying on top of homework?

If you notice flag-raising behavior, try reaching out to the teacher. “You can send an email and say, ‘Hey, just want to check in, does so-and-so look engaged? Are they participating? Do they look happy? Are they talking to their friends? Are they answering questions?’” Rosenthal suggests.

The key is to understand your child — to know their habits and recognize when something is off — and address it in the way that makes the most sense for their own personality.

“There’s no cookie-cutter approach here because every kid is different,” Rosenthal said. “You have to think about what your particular child’s relationship is to school, and then, how to help them.”