My parents had been acting strange.

Like thousands of millennials (or so I’m told), I moved back in with my parents when Covid hit in March, and I never moved out. If you’d told me a year ago that this is where I would be more than a year later, I would have laughed in your face. But it turned out to be the best deal ever: we were like three oddly paired roommates, eating dinner together each night, watching CNN 24 hours a day, and fan-girling over the latest PBS drama series.

But at the beginning of November, my parents left for a trip back to Boston and just sort of…never came back. Our family has two homes — one in a small vacation town in Cape Cod where we had been living during the pandemic, and one closer to Boston. My parents would go back to our home near Boston once a week or so to pick up the mail or make sure the pipes hadn’t frozen, but that was about it…until November.

They made various vague excuses about their sudden absence: the house needed a deep cleaning. They didn’t feel like making the drive back to the Cape. They were reorganizing the garage. I didn’t think too much of it. They have lives that exist beyond me, after all.

Then the weekend before Thanksgiving, my sister and I both made the trip to our home in Boston to celebrate the holiday, as we did every year. My mother had said not to make any plans on Friday night because she wanted the four of us to have a family movie night.

That’s when they told us.

I think my father is the one who said the actual words: pancreatic cancer. Locally advanced. Inoperable. My sister looked bewildered, but I knew the statistics. The average five-year survival rate after a PC diagnosis hovers just above five percent. It is extremely rare, very hard to detect, and almost always fatal.

I don’t quite remember what happened right after they told us, but I do know that I went up to my bedroom and didn’t leave for 24 hours. I cried and slept and cried and slept, until Saturday night when my sister gently knocked on my door. “You need to get up,” she told me. “He’s not dead yet. And who knows? Maybe he’ll be in the lucky 5 percent.”

Even at age 30, I am the baby in the family, and I’ve never been one to take on the lion’s share of responsibility. But when I finally dragged myself out of bed, I decided that I was going to learn everything I could about pancreatic cancer. You may be aware that my boss Katie is a bit of a legend in the cancer world, so I asked her for help. Katie went above and beyond the call of duty to lend my family her help, support, and expertise, as I’ve witnessed her do countless times for both friends and strangers alike.

Over the next three weeks or so, I basically became a doctor. I learned about CA19-9 markers, neuroendocrine tumors versus adenocarcinoma, and the ins and outs of Whipple surgery. I compared doctors and got to know their assistants. I made myself useful. My dad’s tumor had been detected through a CT scan, but before he could start the long and arduous journey of chemo (as well as a clinical trial we had enrolled him in), the surgeon needed to determine the exact course of treatment by taking a sample of the tumor.

Over the next month, my dad had two endoscopic ultrasound (or EUS) biopsies. At that point during Covid, my mother was allowed to sit in the waiting room during these procedures so she could be there to hold my father’s hand once he was out.

Both biopsies came back as negative — no cancer detected. Our oncologist explained to us that this is because a pancreatic tumor is almost like a peanut — it has a shell around it that’s made of scar tissue that won’t register in a biopsy as cancer, but it can spread like wildfire. His tumor was too deep within his pancreas for them to get a sample from the cancerous area through a EUS biopsy. They told us they were hopeful that it hadn’t yet spread to his liver.

I spent those weeks reeling, knowing that each failed biopsy was adding two weeks to the time he could start chemo, which only works to shrink the tumor in 30 percent of cases. After his second biopsy, he had port placement surgery so he could start chemo as soon as we received the positive biopsy result.

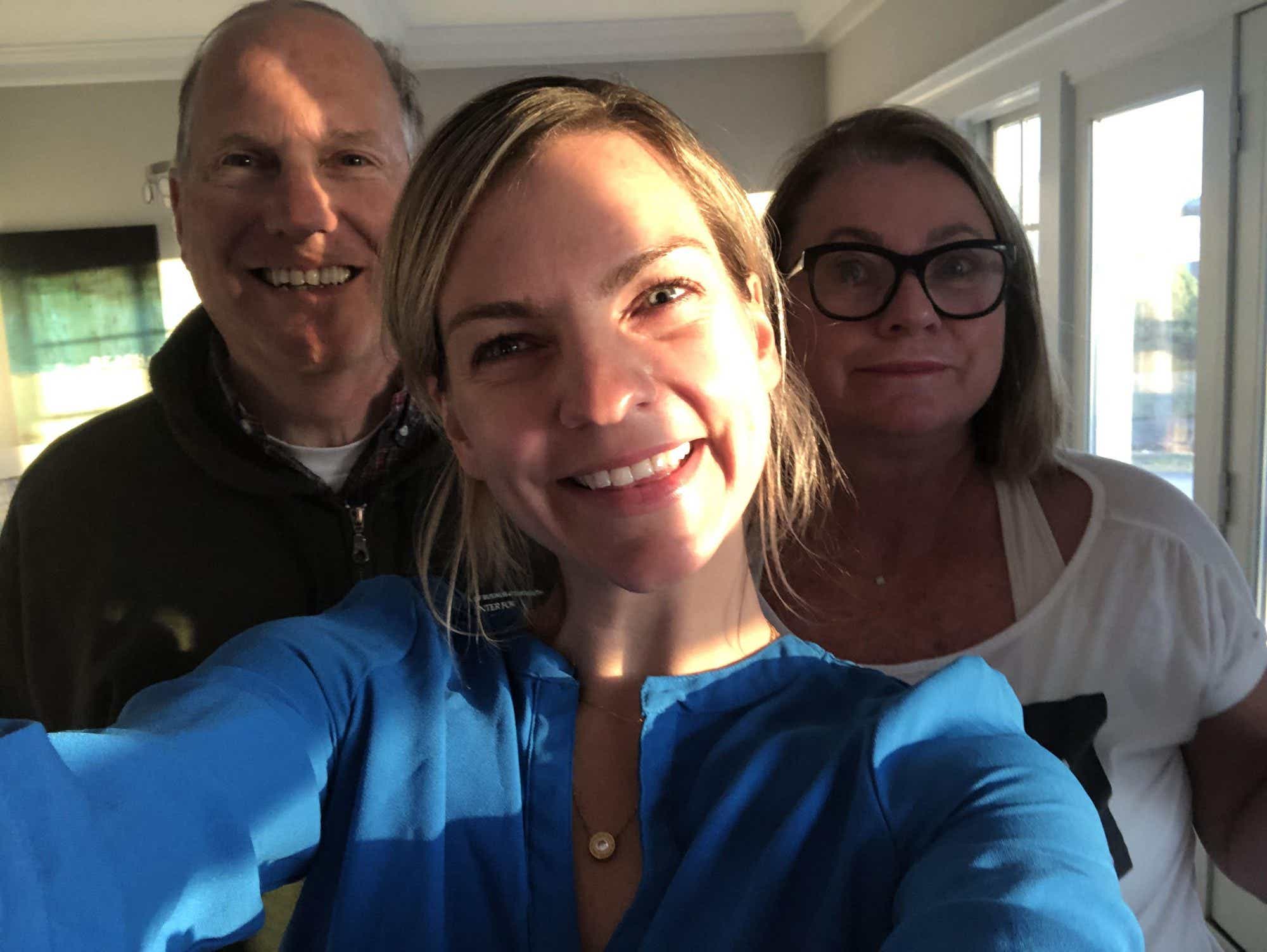

Now, nobody deserves to get cancer. But in my humble opinion, my dad really didn’t deserve cancer. He is kind. He is funny. He still keeps in touch with all of his friends from high school and college. He would get misty-eyed every time he dropped me off at the train station to go back to NYC after a visit home, his voice cracking each time he hugged me and told me he loved me. When I was a child who showed absolutely no athletic ability whatsoever, he got really into musical theater so he would have something to bond over with me. Before his first EUS, he openly cried tears of joy when the phlebotomist told him with pride that her son had just gotten into college, and would be the first member of their family to attend. He is, in short, a really good dad.

When the second biopsy came back negative, our surgeon decided to perform laparoscopic surgery to biopsy the tumor, which is a much more invasive procedure but would ensure that they would be able to get a viable sample.

“Well, I’d rather have another biopsy than an autopsy!” Dad joked, but I could tell he was terrified.

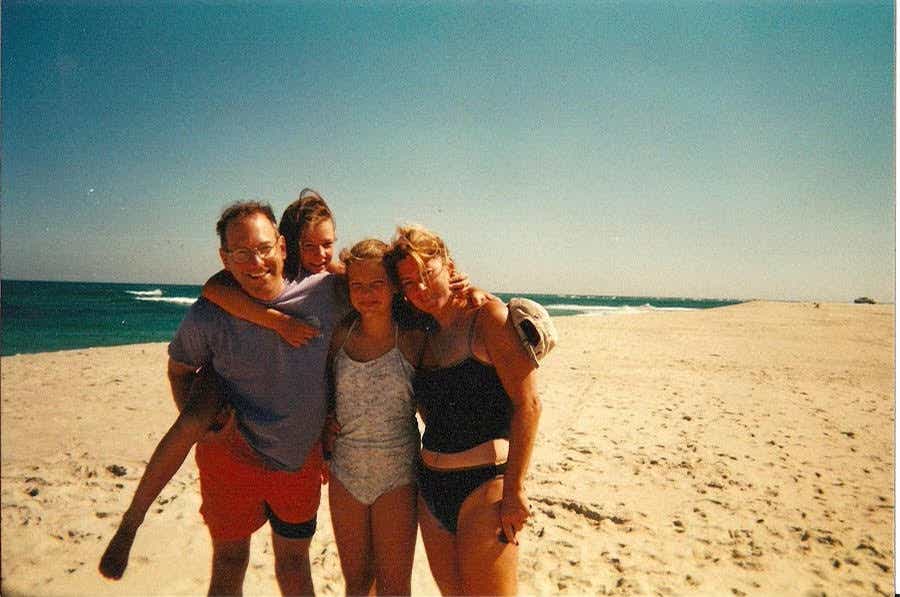

The weekend before his surgery, my sister and I took my dad skiing, which is his favorite thing to do. It was a beautiful day, and although the trails were icy, there were so few skiers that we felt like we had the mountain to ourselves. Nobody mentioned cancer, or hospitals, or five-year survival rates. I will remember it as one of the best days of my life.

That Monday, my dad went in for what was supposed to be a three-hour surgery. Because of Covid restrictions, nobody was allowed into the hospital with him. The surgery started at 8:30 a.m., and by noon we were starting to get nervous. My mother called the nurse, who said there was no update. She called again at 1 p.m. — no update. We were told that my dad was still in the operating room, but if something had gone wrong, we would have gotten a call by now.

My mother, sister, and I spent those hours, the longest hours of my life, snuggled in my parents’ bed, crying and praying together.

Finally, at around 4 p.m., we got a call from the surgeon. He calmly relayed that he took seven samples of the tumor, and his preliminary finding was that none of them were cancerous. At first, we couldn’t understand what this meant. We had been told in no uncertain terms, by multiple doctors, that my father absolutely had a cancerous tumor in his pancreas.

The surgeon, who sounded a little surprised himself, asked us a series of questions. Has your father ever been in a serious car crash? No. Has he ever been hospitalized for severe pancreatitis? No. The surgeon explained that although there was a mass, it seemed quite clear that it was not cancer. I can’t even remember the explanation he gave because I was crying too hard. “It’s like a miracle,” said my mother.

We spoke to a few other doctors who told us “not to break out the champagne just yet” until we got the official biopsy results back on Monday or Tuesday, but that we could be cautiously optimistic. The following week we got the call: the mass, which had presented exactly like pancreatic cancer, appears to have been scar tissue from an unknown cause. My father was released from the hospital on Christmas Eve.

When my father got home, I felt like I had whiplash. We were told in November that my dad, my favorite person in the world, 100 percent had cancer. And not just cancer — the WORST kind of cancer. We met with an estate planner and got his affairs in order. My mother and I signed paperwork saying we were willing to make decisions about end-of-life care. We were told to expect about nine excruciating months. Now, about three months after the laparoscopic surgery, after his port was taken out, and after a number of clean scans, we are being told he is going to be fine.

I am so grateful — BEYOND grateful — that my father is still with us. That we will get to go skiing together again. That we have endless more nights to snuggle on the couch and watch PBS dramas together. That he will hopefully one day get to meet my future children (don’t read too much into that one, mom). And yet, I feel this giant albatross around my neck…why us? Everybody prays that their loved one will be OK, that it will all be fine, but parents lose their children to cancer every single day. Partners lose spouses. Lives are constantly, irreparably ripped apart by this disease. Why did God answer our prayers, and not somebody else’s? What did we do to be spared, and how do we even begin to handle that sort of responsibility?

People keep asking me, “Are you so happy? Are you jumping for joy?” The answer is no. The answer is that I feel traumatized. My family just endured some of the most painful, confusing, stressful, anguishing months that any family could possibly go through, only to be told it was all for nothing. I feel angry. I feel guilty. I feel like there is a small, dark oil stain that has developed on my heart that I can’t scrub off no matter how hard I try. I don’t tell people this, of course. Instead, I say, “yes, we are absolutely thrilled. We are now living in a constant state of joy-jumping.” It’s easier than trying to explain the oil stain.

I had decided to volunteer for the Boston chapter of PanCan, the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, when my father was first diagnosed. They are an incredible group of dedicated family members who have lost loved ones to this horrible disease. After it turned out that my dad was “fine,” that ours was a “false alarm,” I felt immense shame explaining my connection to the disease at the beginning of each meeting. “I thought my dad had pancreatic cancer but he’s actually fine…but I’m so sorry for your loss…” I couldn’t handle the guilt. Without warning, I stopped showing up for the meetings. I literally ghosted a cancer volunteer group full of kind, loving, nonjudgmental people who made me feel so welcome regardless of the fact that my connection to their cause was now, for all intents and purposes, nonexistent. Who does that?

What happened didn’t magically transform me into a better person. I don’t tip waitresses any more than I used to, or suddenly walk patiently behind slow walkers, or pay for the person’s breakfast sandwich in line behind me. I still feel a pit in my stomach every time I get a call from an unknown number, because that’s how calls from the hospital would show up on my phone. In those days when we were waiting for my dad’s biopsy results, I screamed and cried into the phone at many a shocked telephone scammer.

My relationship with my dad hasn’t even really changed that much. I don’t tell him that I love him any more than I used to, or feel less annoyed with him when he puts a cereal box that is basically empty back in the pantry. I’d like to think that this is because we had a pretty good relationship to begin with, but I really don’t know.

People also ask if my father has a new lease on life. I think at this point, the answer to that is also no, although the first thing he asked when he woke up from surgery and found out he was going to be fine was, “Can we go skiing again?” Frankly, I think this whole ordeal scared the sh*t out of him. Every time he feels an ounce of pain, or shortness of breath, or loses his train of thought, he’s terrified that it’s cancer and that they made a mistake.

We are so blessed. I know this. But we have also been shaken to the core. The combination of feelings is overwhelming and nearly impossible to explain. All I can hope is that with time, the anger and confusion and terror will melt away and leave only gratitude and that gratitude will propel us to do something worthy of the gift we were given.

*A special note from me: Please consider donating to PanCan. They are remarkable people who are doing remarkable work.