I’m fascinated by the human body and how things can go awry in our intricate and complex systems. Our bodies are set up to stop bad stuff (like disease) from happening, but sometimes it can go into overdrive. Acute inflammation is meant to help the body fight off infection and heal from injury, but it often malfunctions — and when it does, it can wreak havoc. Experts believe chronic inflammatory diseases are the most significant cause of death in the world today, with more than 50 percent of all deaths being attributable to “inflammation-related diseases such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and autoimmune and neurodegenerative conditions.”

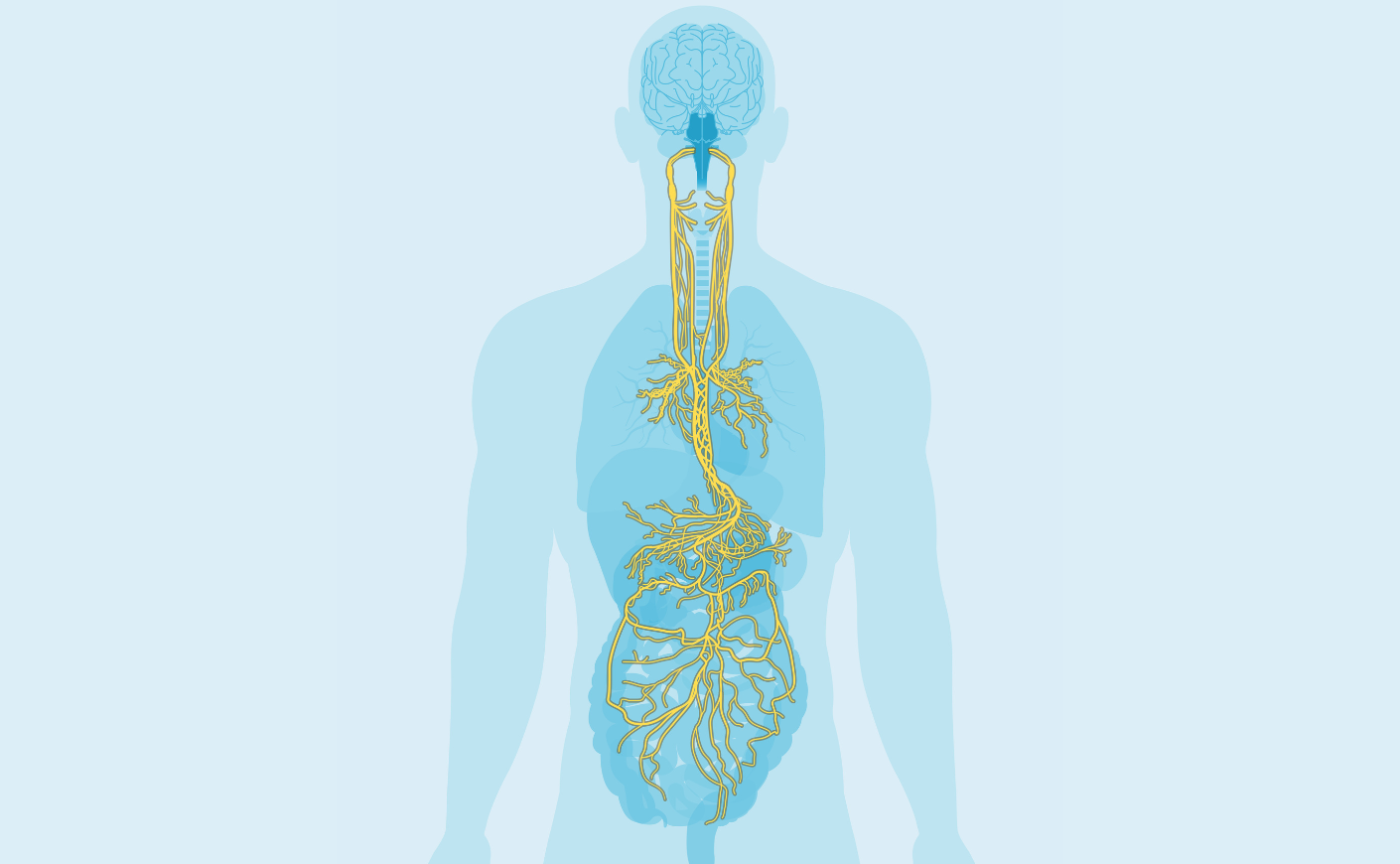

For decades, researchers have been searching for ways to rein inflammation in when it gets out of control. Kevin Tracey, M.D., the president and CEO of Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, believes he may have landed on a solution: The vagus nerve — a bundle of 80,000 fibers that runs from the brainstem to the spleen, lungs, and liver — “could act as a set of brakes for inflammation,” he tells us.

Dr. Tracey made the discovery by accident back in 1998 and has worked on developing a process to seize on the nerve’s capacity to tame inflammation ever since. He now has a therapeutic in clinical trials, which if approved by the FDA would be a “game changer” for the management of rheumatoid arthritis, he says, and could one day be used to treat Crohn’s disease, diabetes, and even cancer.

I spoke to Dr. Tracey about the nerve’s outsized impact on our overall health, how his cutting-edge device works, and the promise the technique could have for treating a wide range of chronic conditions.

Chronic Inflammation Symptoms

Katie Couric: Can you explain what inflammation is and how it protects the body?

Dr. Tracey: So inflammation at the highest, simplest level is what happens when your body either is injured or infected. If you twist your ankle, or if you have an infection in your ankle, you get redness, swelling, pain, and a loss of function in that ankle. That's inflammation.

So the redness and whatever's happening on my ankle is a result of my immune system jumping into action to heal either the injury or the infection?

That's exactly right. In the early phases of an injury or infection, you have either pathogens or damaged tissue. White blood cells called macrophages are sent to gobble up the damaged tissue or the pathogens. In the process of doing that, they call in other white blood cells, which all have very specific job descriptions and aid in the healing process to bring the body back to a baseline, called homeostasis.

What happens when homeostasis isn't reached and the immune system keeps trying to heal something but ignores when it's healed and wants to keep going and is sort of out of control?

The excess of inflammation, or what you call the loss of homeostasis is called disease.

40 million people every year die of inflammation, but that's not what is on their death certificates. How does inflammation lead to all these very serious chronic conditions?

To start with a simple example, let’s take sepsis, which kills millions of people in the world every year. Its root cause is some pathogen, E. coli, streptococcus, or some other bacteria. Sometimes, people who die of sepsis have pneumonia listed on their death certificate, when in fact, the underlying problem with sepsis is excessive inflammation.

There's a lot of new work that is occurring around inflammation in cancer. One thing inflammation does is stimulate healing and the growth of new cells. In cancer, when you stimulate cells to grow, you can end up with metastasis or spread that cancer into new parts of the body. Some cancers actually make cytokines — a signaling protein that can either stimulate or reduce inflammation — and use them as a growth factor.

How do you know if you have this type of dangerous chronic inflammation?

You could get a blood test that would look at different inflammatory markers in your bloodstream, things like cytokines, high levels of IL-6, and C-reactive protein, for instance. If you have an elevated white blood cell count or abnormal distribution of the percentage of different white blood cells, that can be a marker.

Vagus Nerve Function and Location

How did you first learn that there’s a connection between our brains and how inflammation is regulated?

By accident. We were working in the lab on animals with brain damage, giving them a drug that we thought would stop inflammation in the brain and help their strokes improve. But what we didn’t expect was that their inflammation would vanish throughout their bodies too.

We were scratching our heads for months, but then we cut the vagus nerve in the necks of these animals and found that the drug no longer had the same effect. So from that, we knew that this conduit — the 80,000 fibers of nerves from the brain to the spleen and the lung and the liver — could act like a set of brakes for inflammation.

So when you’re sick, is your vagus nerve helping to keep your immune system in check?

That’s what the evidence shows, that it’s emitting an ongoing signal to slow inflammation. We’ve proved this in animals: We’ve shown that when you damage the nerve in one it’ll go on to develop more severe complications from inflammation than one that has its vagus nerve intact. And there’s evidence of this in humans too. There were studies out of Spain that found that people with a severe Covid infection also had severe damage to their vagus nerve, and this seemed to be the cause of many of the symptoms of even long Covid: fatigue, excessive inflammation in the muscles and joints, difficulty breathing.

So if the brakes to your inflammation system are failing then exposure to a pathogen or a virus that maybe wouldn’t affect a healthy person is going to activate dangerous inflammation in people with a damaged vagus nerve.

Is it correct for me to conclude that if you have a disease associated with inflammation, there’s a chance your vagus nerve has malfunctioned?

That’s fair. If you look at patients with some of the more common autoimmune diseases, like multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or inflammatory bowel disease, you’ll see that their vagus nerve activity is impaired compared to healthy people. On the flip side, there’s evidence that enhancing your vagus nerve activity protects against damage from inflammation. One of the best indicators of increased vagus nerve activity is a slow heartbeat. And what slows your heart rate? Aerobic exercise. There’s no consensus in science or medicine on why exercise is good for you, but it might be because it’s increasing your vagus nerve to keep your inflammatory systems under control. It might be as simple as that.

Can you get your vagus nerve tested?

Not really, although some people have been looking at one metric called heart rate variability (HRV). So every time your vagus nerve fires, it slows your heartbeat by prolonging the time to the next heartbeat. If you have a high HRV and a slow heart rate, you probably have a high level of vagus nerve activity. But this is not something you’d get done at the doctor’s office, there’s no simple way to do it except to check your pulse.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Tell us about the work you’re doing to stimulate the vagus nerve to reduce inflammation.

After these experiments, my colleagues and I realized that we should be able to turn this signal on by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve. We did that in 1998, and it worked in mice. We saw that they were protected against subsequent inflammation for many hours and sometimes days. In 2007, I filed a patent for that tech and launched my company. What’s so exciting is that within the next year, I think we’ll reach a tipping point. There’s an ongoing clinical trial of 250 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and I’m very optimistic it’ll work.

If the FDA approves vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for RA, it’s a game changer. It’s going to disrupt everything because patients don’t want to take the current antibody treatments available — they cost $100,000 a year, have black box warnings, they’re invasive, they have to be injected, and they only work half the time. Our device would be implanted in the neck, and I’m not sure exactly what the cost would be but it’d be less than taking the drug for a year.

Can stimulating the vagus nerve be preventative? Could it be used to prevent the progression of a disease or even the appearance of a disease?

Yes. I think that will be coming in the future. We know enough about how inflammation contributes to important diseases, and what we have to learn now is how to actually apply that to clinical situations. Some people tend to wave their hand and say, “vagus nerve stimulation,” but it's a little more complicated than that. There are 80,000 fibers in your vagus nerve on one side, there are 80,000 on the other side. So what we're doing now is we're diving into those fibers and trying to identify which ones are linked to which diseases, so that we can perfect devices to target them.

What other things might vagus nerve stimulation be able to treat besides rheumatoid arthritis?

I think soon there will be clinical trials for things like Crohn’s disease, diabetes, and multiple sclerosis. And soon after that — in cancer. There’s some evidence that stimulating the vagus nerve can change the course of cancer in animals. I think you’ll see the floodgates open in terms of clinical interest in this space.