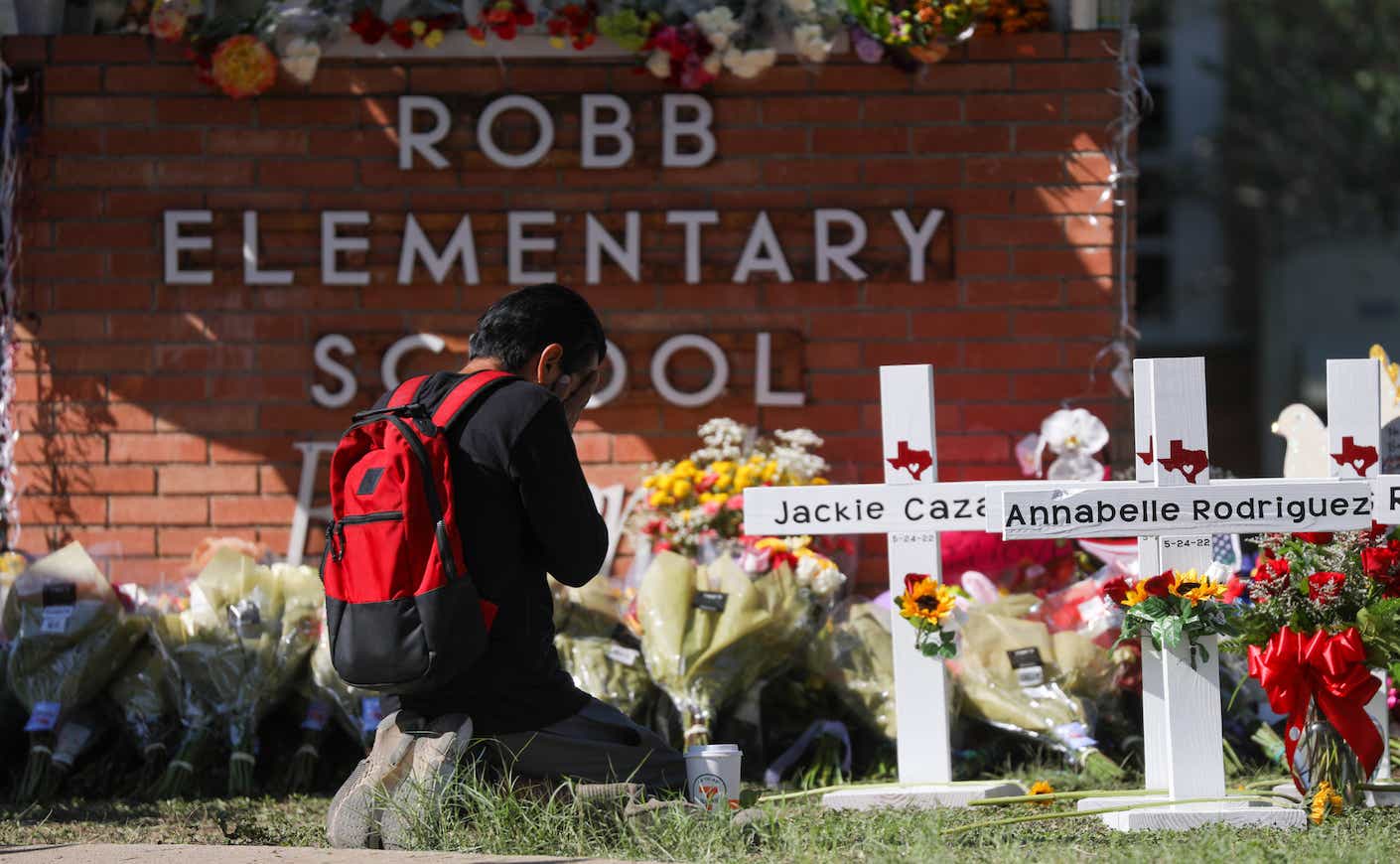

In the aftermath of another school shooting, my social media feed is full of friends talking about the mental health crisis and calling for more funding for mental health services. As a clinical psychologist and co-founder of a start-up whose mission is to increase access to mental health care, I should be excited about the national attention on youth mental health. But I’m not. Framing the latest tragedy as a mental health crisis is both factually incorrect and also very harmful. And I understand why mental health becomes the narrative: Regardless of where you fall on the political spectrum, inaccurately framing it as a mental health crisis makes us all feel safer.

First, the facts

Research has consistently demonstrated that mental health is not a predictor of violence (people with mental illness are more likely to be the victim than the perpetrator), that gun control laws targeted at the mentally ill have had zero impact on reducing homicides, and that the best predictor of who is going to hurt people is their gender (male) and if they have access to guns.

But why does it feel like it’s a mental health issue?

For the past decade, whenever a tragedy occurs, both professional media and social media repeatedly ask the same question: Was the shooter mentally ill? This has created a false association. We DO have a mental health crisis, and the multi-year pandemic and exponential increase of social media haven’t helped. And sadly, America has always had too many children and teens struggling with mental health. As a society, we have gotten better at recognizing, diagnosing, and talking about mental illness — but it’s not because it’s new. We all have anecdotes: My high school had four deaths by suicide in the mid-90s; we hear our parents’ generation reflecting in hindsight, “I had a kid in my class that probably had [insert mental illness here], we just didn’t have a name for that when I was a kid.” And the data shows the same thing: Gun violence has not been increasing proportionally to mental illness rates, and while mental illness has been increasing worldwide, other countries with similar mental health problems do not have the same rates of homicides or mass shootings.

Why do I want it to be a mental health issue?

As humans, as mammals, we instinctively fear our own death, and the death of our children and loved ones. And it would be paralyzing to be aware, every minute of every day, of each risk that we take when we cross the street, ride in a car, or walk into school. And thus when tragedies like this occur, it forces us to confront our own mortality. So, our brain, both subconsciously and consciously, searches for facts that help us to feel safe, to prove that we are different than those that perished and that those differences will keep us alive:

- The car crash victim wasn't wearing a seatbelt — I always wear mine.

- The cancer victim didn’t eat organic and I do — I’m probably less likely to get cancer than they were.

- The school that was shot-up was in a low-income community and we don’t have “kids like that” here.

By labeling the shooter as mentally ill, as an outcast, as a “child who didn’t know God” as one social media post shared, we can lie to ourselves that “those kids” don’t go to my kid's school, “those kids” don’t live in my community, and we can pretend that we’re safe.

The truth is much scarier. None of us are completely safe 100 percent of the time. There are risks to our health and safety everywhere, every day. And after each tragedy, when we blame “mental illness,” we ignore the truth and the data: In America, dangerous people have unlimited access to dangerous weapons. And no amount of talk therapy, prevention programs, or organic food is going to rid the world of all dangerous people. Can we stop blaming mental illness long enough to make dangerous weapons finally disappear?