In 2018, when the U.K. appointed its first “Minister of Loneliness,” it was interpreted stateside as little more than a headline seemingly tailor-made for late-night monologues. SNL’s Colin Jost joked that the “minister of loneliness” also happened to be his “nickname in middle school,” while Stephen Colbert quipped that the new position sounded like the title of a Morrissey album.

Granted, at the time it did come off as some British eccentricity. Most of our government titles are straightforward, bland, and named for issues that at least feel concrete, like the Secretary of Transportation or the head of the Centers for Disease Control. To task someone with vanquishing a slippery emotion like loneliness just seemed, well, bizarre. But that was five years ago, before a global pandemic forced us to cut ourselves off from each other physically. Now, more of us have come to accept that loneliness, as former U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May put it, may really just be a “sad reality of modern life.” Japan has followed suit in appointing its own loneliness czar as the number of suicides there has risen. And here, medical experts are sounding the alarm on what they’ve taken to calling an “epidemic of loneliness.”

Have we gotten lonelier?

Studies seem to indicate that we as a nation are growing more starved for intimacy and companionship. In a 1981 Gallup poll, about 20 percent of Americans reported feeling “lonely or remote from other people.” While 36 percent of respondents in 2020 said they were grappling with “serious loneliness.”

Not everyone studying the phenomenon believes it’s the case that the country’s being swallowed by ennui — in part because the emotion is hard to measure and we don’t have a ton of reliable data that dates back all that far. But what is becoming clear is that loneliness poses a serious health threat, says Jeremy Nobel, MD, founder of the UnLonely Project and faculty member at Harvard Medical School. The condition has been tied to higher rates of cardiovascular disease, dementia, and shorter lifespans.

“Loneliness won’t just make you miserable, it can kill you,” Dr. Nobel tells us.

Why are we so lonely?

That recognition has spurred researchers to investigate why so many of us now feel so disconnected. And they’ve come up with a wide array of culprits, placing the blame on everything from the gig economy to urbanization. But no consensus has emerged.

Americans are certainly more solitary than they once were. In 1950, less than 10 percent of us lived by ourselves, now close to 30 percent of households consist of a single adult, according to census data. Of course, solitude is not the same as loneliness, Dr. Nobel and others in the field are quick to point out. But some believe our decline in face time is contributing to this growing sense of isolation.

The 2000 book Bowling Alone by Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam documents America growing apart. He argues that factors like suburban sprawl, the rise in two-career families, and television’s monopolization of our leisure time had led to a decline in community engagement that began after the Second World War and has only accelerated since. Americans began hosting fewer dinner parties and card games, while membership in organizations like bowling leagues, the PTA, and the Knights of Columbus have plummeted — leaving us with fewer opportunities to see one another. The pandemic and remote work have only led us to drift even further apart, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy writes in his 2021 book on the loneliness epidemic, Together.

The role technology plays

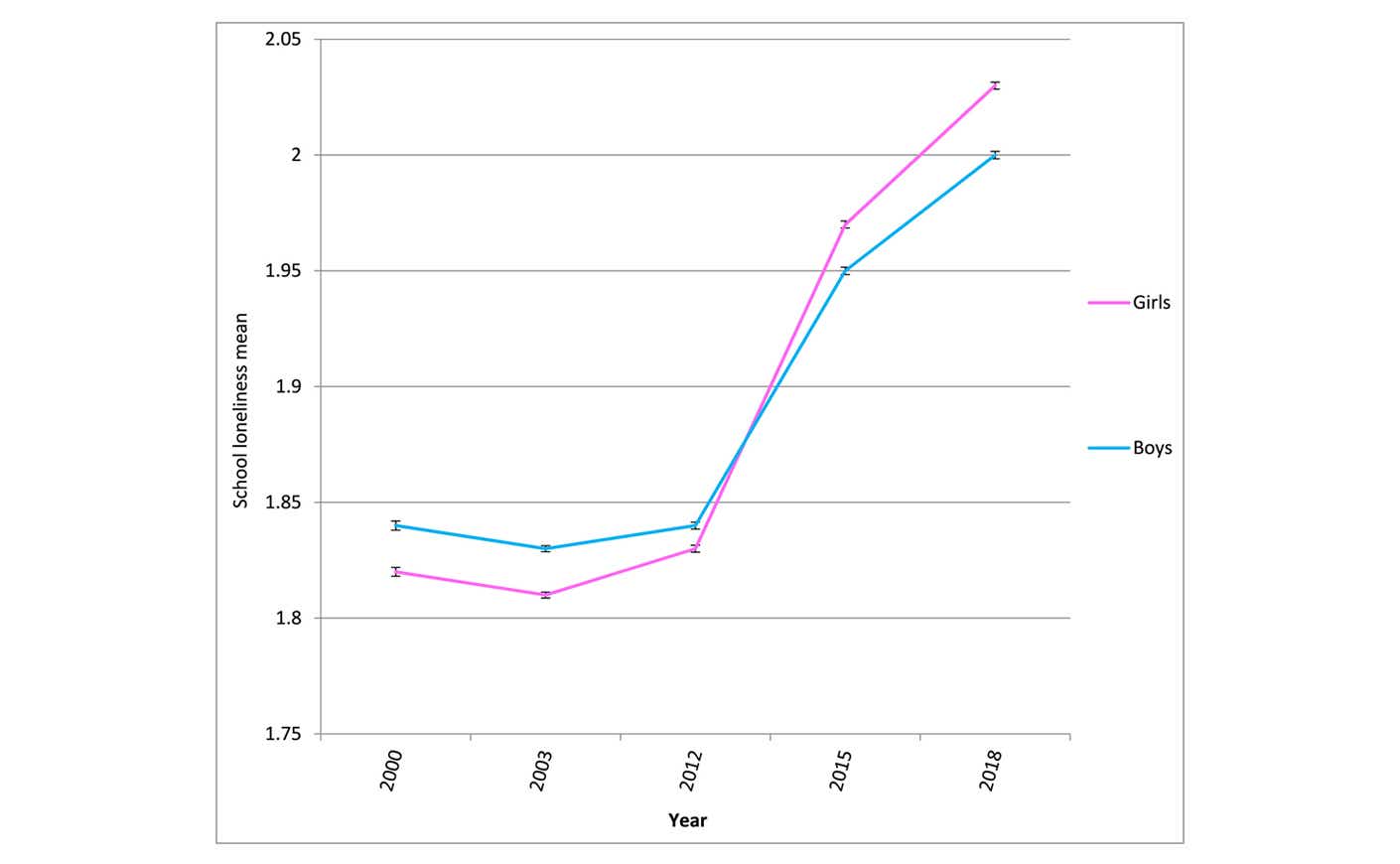

Smartphones and social media were meant to fill this void and in a lot of ways they have. Families scattered across the globe, who once could only rarely interact can now Zoom whenever they want; members of marginalized groups can now easily find each other on Reddit. But many are starting to believe that TikTok, Twitter, and our compulsion to tag, share, and like are only making the problem worse. In a 2021 study, psychologists Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge point out that loneliness in teens, according to a survey that gauged well-being in schools across 37 countries from 2000 through 2018, had mostly remained steady up until 2012, when suddenly it spiked. What the heck happened in 2012?

Twenge and Haidt believe two things unfolded. 2012 was a tipping point, the moment when the majority of Americans began owning smartphones, they found. And by then, Facebook and Twitter had undergone a profound shift in how they kept users hooked to their sites, completing their metamorphoses into full-on “outrage machines,” while Instagram, which has since proven toxic for teen girls in particular, had become an all-consuming app for millions, they write. They analyzed other possible contributing factors, like the decline in family size and increases in unemployment, but found that “only smartphone access and internet use increased in lockstep with teenage loneliness.”

Twenge and Haidt hit on a contradiction that’s concerned others, too: The more connected we become online, the lonelier we seem to grow. Why? They suspect the smartphone has fractured our attention. Instead of talking to strangers at a bar or in line at the local coffee shop, we scroll. And even when we do engage, it’s hard to have an exchange of any depth when the intermittent buzzing in your pocket is a reminder of the world of things you could be liking, sharing, or responding to.

It’s that sense of yearning for the vast universe of engagement and cheap thrills the internet offers up that Weber State professors Luke Fernandez and Susan Matt believe is at the root of our modern state of desolation. In their book, Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid, the husband-and-wife team examines the work of Letitia Anne Peplau, an early loneliness researcher at UCLA, who defined the emotion as the psychological discomfort that results when we want more, or richer, relationships than what we have. “She thought loneliness sprang up in that disparity, that gap between your expectations of connection and your reality,” Matt tells us.

What social media has done, Fernandez and Matt argue, is greatly expanded our desire for intimacy. Before the internet, the number of friends you could have was bounded by geography and the hours in the day. Now, we can call, text, and FaceTime with anyone, virtually whenever we want; we can “friend” hundreds of people from around the globe in a single afternoon. Influencers have amassed millions of followers by offering a modicum of closeness — live-streaming their trips to the mall, showcasing their morning routines — to create an illusion of intimacy that’s invariably shallow. All that’s led Americans to forge “a new sense of self,” the researchers say, one that feels entitled to an “unlimited number of social connections.” And that’s had the effect of stretching that gap, identified by Peplau, between what we want and what we have, leaving so many of us aching from a perceived lack of companionship.

But it’s not only this relative deprivation that’s feeding America’s loneliness problem. Some think that our phones — which have made it possible to FaceTime your mother in Michigan one minute and text your daughter in Los Angeles (reminding her to call her grandmother) the next — have eroded our ability to be alone. Just look at your phone: How many text, Facebook, or Instagram messages have you sent in the past hour alone? If you’re like most hyper-connected Americans, it’s probably a lot. We’re social creatures after all, and the urge to connect is hard to resist. But sending or receiving “a hundred text messages a day creates the aptitude for loneliness, the inability to be by yourself,” the literary critic William Deresiewicz writes in a 2009 essay.

This would suggest the ache so many of us feel is culturally conditioned, but that doesn’t mean it’s still not painful. The longing to feel understood and welcomed is an instinct that was hardwired into us 52 million years ago as primates, Murthy writes. That’s what makes the grief of estrangement so devastating. And why more experts are trying to unravel why technology or some other force has made loneliness feel like a “sad reality of modern life.”