Most of us have heard of the body’s survival instincts: fight, flight, or freeze. But psychologists say there’s a fourth — and often overlooked — response: fawning. It’s the reflex to appease, please, or bend ourselves out of shape to avoid conflict or danger. Unlike the others, fawning can look socially acceptable, even admirable. But research shows that chronic people-pleasing takes a toll, fueling anxiety, burnout, toxic relationships, and poor boundaries.

In her forthcoming book Fawning: Why the Need to Please Makes Us Lose Ourselves — And How to Find Our Way Back (Putnam, September 2025), psychologist Dr. Ingrid Clayton explores how this pattern takes root and why it’s so hard to break. In the excerpt below, she introduces “Grace,” a patient who learned early on that safety meant abandoning her own preferences. Grace’s story shows how self-erasure can feel like protection in the moment, but over time, costs us connection to who we really are.

Grace was in her 40s when we started working together, and her stated reason for coming to therapy was because she wanted to be a good mother. She knew she'd had a problematic childhood, and she didn't want to repeat the patterns in her own parenting.

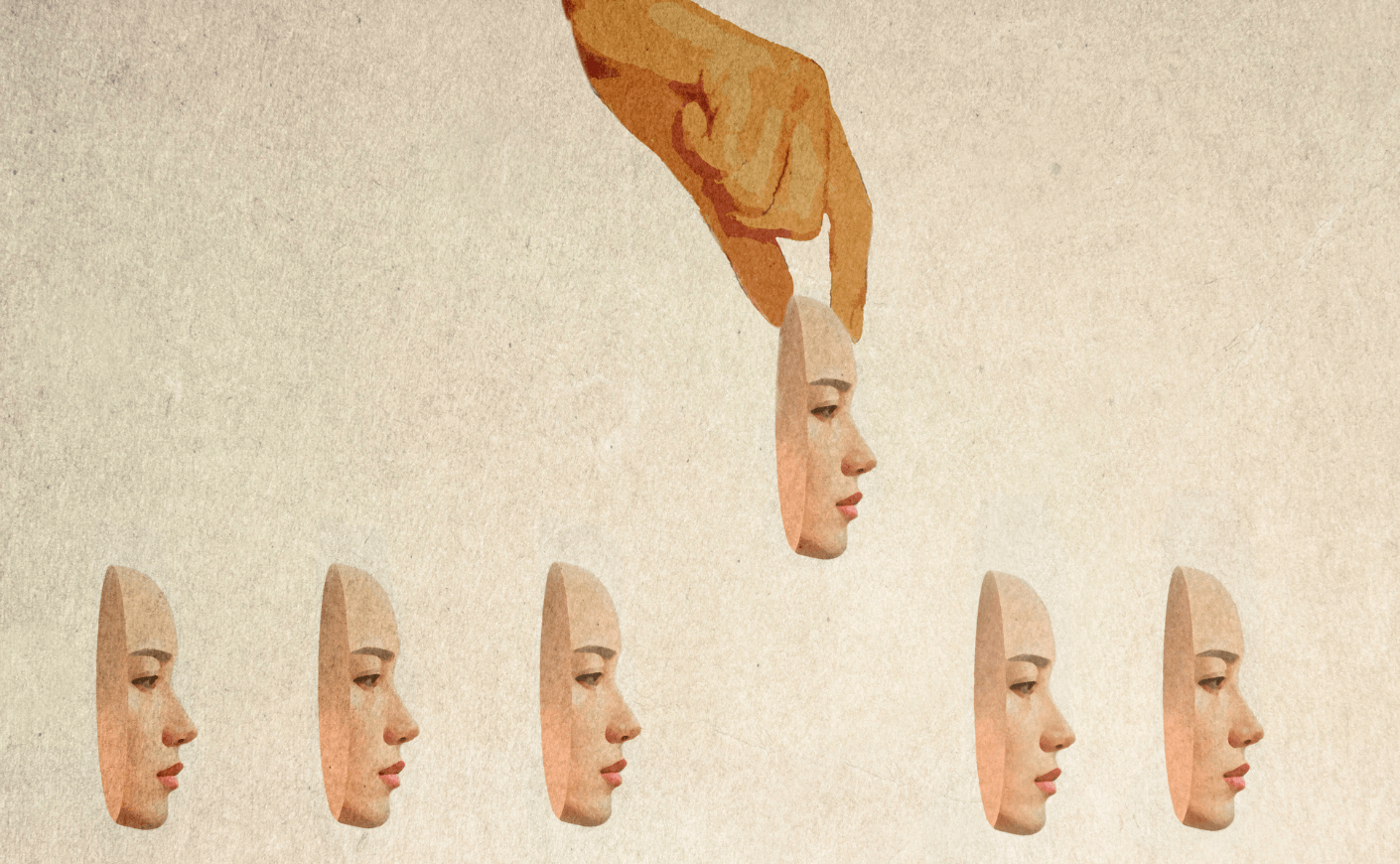

Early on, Grace shared that she wore "different hats" depending on the situation she was in. She was a different person at home, at work, with old friends. She knew if her husband was hanging out with the work version of her, he wouldn't even like her. Her different personalities in various contexts had become so pronounced, when Grace read the book Sybil, she wondered if she had dissociative identity disorder.

As she shared the complicated adjustments she had to make to be the right person in each context, I mentioned an analogy that might help her identify how taxing these roles were. "It seems like you're walking a tightrope," I said. Then I asked her if she longed for more freedom.

"It's definitely a tightrope," Grace agreed. "But I love it!"

That wasn't what I was expecting. But Grace explained that knowing where to step made her feel safe. "The idea of having more room, of stepping a millimeter to either side, feels terrifying. Like I'm going to set off a land mine."

The constraints were comforting. She liked it when someone told her what to do, who to be. So she surrounded herself with opinionated people who told her exactly that.

It would take many more months for Grace to realize what all these masks were costing: access to her true self. At the time, she could see her pliability only as helpful, just the way she always was.

Shapeshifting isn't always about winning a popularity contest (although many of us would like to win it!). Sometimes our shapeshifting looks like doing drugs to stay with the in-crowd. Or gossiping to appease a friend. Shapeshifting is how we learned to manage the relational gap. When we couldn't express or meet our own needs, when we couldn't trust others to do their part, we had to close the gap by morphing into whatever the situation called for.

As Grace and I explored her compulsion to orient toward what others wanted from her, she told a story from her childhood. Her dad was explosive, punishing, with a "you made me do it" attitude. He often told Grace she was stupid, that she wasn't listening or trying hard enough, that it was always her fault.

One morning in high school, her dad said, "Let's order pizza tonight," before she headed out for school. He then asked if Grace wanted onions. She was putting away her cereal bowl when she said no and turned to grab her backpack. Her dad erupted: "You always like onions, and now when I ask you, you say you don't like them?!" He was raging and Grace was frightened.

To escape further confrontation, she tried to leave through the back door. Her dad dragged her by her hair to the front door and then kicked her from behind, ejecting her from the house.

While I'd heard of the volatility in her childhood home before, this scene was clearly painful for Grace to recount. She began to analyze what happened, why her dad reacted that way. "My dad was portraying thoughtfulness, saying he'd order pizza for dinner and wanted onions, and my job was to want what he wanted. To know what he wanted. But he didn't really care. The truth is, he wanted me to want what he wanted. When I didn't do that in childhood, I was punished." She seemed resigned as she presented her analysis.

To this day, sharing food is terrifying for Grace. She hates potlucks, fearing she'll bring the "wrong" thing. Every decision or opinion is an opportunity to upset someone by not doing things their way. As a result, Grace developed a lifelong commitment to become whatever the situation called for. She likes onions because, as she shared, "Everything I do is to de-escalate!"

When we've learned to de-escalate by contorting ourselves, healthy conflict becomes incredibly difficult. We don't know if we are in relationships that can support it and we don't want to risk trying. Our bodies are keeping a perpetual eye out for new threats, so even potential upset is overwhelming. We might interpret hints of disappointment as "it's happening again," and automatically say we like onions rather than face being violently kicked out of the house. Building new capacity means facing the fear and overwhelm we've instinctively turned away from, for good reason.

Noticing all the ways Grace had contorted herself over the years, I said, "It's as though you've never truly been seen. Not by others, not even by yourself." With tears in her eyes, Grace nodded yes.

This is the cost of shapeshifting. We lose access to ourselves. Grace's path forward involved the slow, frightening work of reclaiming the parts of herself she abandoned to keep others comfortable. She learned to stay connected to her own responses — her preferences, her boundaries, her instincts — even when they create friction with others. The goal isn't to become someone new, but to stop betraying who she'd always been underneath the masks. For many of us, this same work awaits: the gradual process of retrieving the pieces of ourselves we scattered along the way to maintain peace, approval, or safety.

From Fawning: Why the Need to Please Makes Us Lose Ourselves—and How to Find Our Way Back by Dr. Ingrid Clayton, published by Putnam, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2025 by Dr. Ingrid Clayton.