Many of you might know from reading my memoir that I suffered from an eating disorder in my late teens and early 20s. But let’s face it: So many of us have an unhealthy relationship with food. Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm by Emmeline Clein, is one of the smartest, most well-reported books I’ve ever read on the root causes of our culture’s disordered eating. Emmeline examines how our obsession with food and body image has permeated literature, history, and pop culture and how the weight loss industrial complex has exploited our fears and insecurities. While she writes about anorexia, bulimia, and EDNOS (eating disorders not otherwise specified), she also tackles something even more prevalent: binge eating disorder, or BED. I found her book fascinating and insightful. I was also really excited to record a podcast with Emmeline along with my special plus one, my daughter Carrie who has struggled with some of the same issues I faced when I was young. Look for that episode to drop next week. For now, here’s an excerpt of Dead Weight, but the entire book is worth reading. - Katie

The 18-year-old girl only ate in the dark. In daylight, she swallowed little more than scraps. But with her family asleep and the sun down, she sat in the shadows and shoved food in her mouth. She went to see her doctor for an unrelated issue, seeking treatment for migraines. The doctor saw her size and referred her to the hospital’s nascent obesity department. In 1955, she confessed her habit to Dr. Albert Stunkard, a specialist in the newly formed field of obesity studies. He told her to adopt a calorie-restricted diet, as he told most of his patients, but found himself unable to forget her strange story. Soon, more women seeking weight loss treatment showed up in his office, tearful and telling secrets eerily similar to that teenager’s.

They nearly starved themselves all day long, but once the moon rose, they followed the electric hum and fluorescent glow of refrigerators and microwaves and found themselves in their kitchens in the moonlight. With no one watching, they couldn’t stop eating. The doctor was startled by the patients shifting in their seats as they spoke softly, words spilling into each other once the listing began. He scribbled notes, nodding. Name brands and numbers, cuts of meat and quarts of sauces, cereal brands. In the light of day, these women didn’t just diet; they often restricted their intake to levels Stunkard called “morning anorexia.” These women were also fat at a time when obesity was still a small medical field and a semi-rare phenomenon, with only 9 percent of the U.S. population officially deemed overweight. During those brightly lit hours of hunger, many of his patients thought about food constantly, distracted by dreams of what they might eat, even as they promised themselves they wouldn’t.

Night fell, they couldn’t rest, and hours later, full and finally falling asleep, they promised themselves, the universe, and any god that might be listening that they would turn over a new leaf the next day. They saw their binges as crimes not only against their diets, but also against morality, understanding themselves as sinners. One compared their behavior to a murderer’s. Ashamed and afraid of weight gain, the next morning they wouldn’t eat, planning to go to bed hungry in the hopes of reversing what they’d done the prior night. By nightfall, their growling stomachs sowed fantasies of food, and they found themselves back in the kitchen.

Stunkard called this problem night eating syndrome in a 1955 paper. He laid out the symptoms: “morning anorexia, evening hyperphagia [pathological overconsumption of food], and insomnia.” His patients had come in seeking weight loss, so he referred them to diet clinics, where they were taught calorie restriction, the prevailing approach (then and now) to the treatment of obesity, which (then and now) usually resulted in little to no long-term weight loss. Instead, patients attempting to follow restrictive diets often started bingeing more frequently, or experienced initial success followed by a return to intensified bingeing. Both groups developed what Stunkard termed “the dieting depression”: “emotional disturbances during efforts at weight reduction,” usually also accompanied by post-diet weight gain.

Soon, Stunkard hypothesized a “relation between the eating pattern and life stress” — perhaps this "night-eating syndrome" was a stress response to patients’ “failures” in weight loss treatment, or to the fact that if successful, such “weight loss was accompanied by disabling emotional illness.” A body rejecting a diet, not indicating its need for one. Stunkard also observed binges occurring during the day that provoked shame and secrecy, just like night eating. His patients experienced “awesome distress” and “bitter self-condemnation” post-binge, committing themselves in its wake to “quixotically austere diets, usually of very short duration,” followed by another binge. Neither binge eaters nor night eaters responded to weight loss treatment, leaving him “convinced that weight-reduction programs were not nearly as effective as was generally believed” and that they “might not be harmless,” but instead emotionally destructive and physically dangerous.

It wasn’t just binge eaters and night eaters who didn’t respond to weight loss plans based on calorie restriction. A vast majority of Stunkard’s overweight and obese patients didn’t lose weight on diets. Those who did often regained the lost pounds (and more) following treatment. Stunkard was one of the first scientists to notice and admit that dieting didn’t work and often triggered depression. Without using eating disorder terminology, he effectively acknowledged that dieting could cause eating disorders, noting extreme emotional problems, gastrointestinal issues, and dangerous eating habits in the wake of diets.

In a 1959 paper, he used thirty years of data to show that 95 percent of restriction-based diets failed to cause long-term weight loss in obese patients. Today, studies have repeatedly found that around 80 percent of dieters do not maintain their weight loss for even a year, and up to two-thirds regain more weight than they originally lost. The chances of long-term weight loss are lower for larger people—a 2015 study reported that the likelihood of “attaining normal body weight was 1 in 210 for men and 1 in 124 for women” deemed obese, or less than a single percent chance. Stunkard emphasized that periods of calorie restriction were often followed by, and perhaps even induced, compulsive binges.

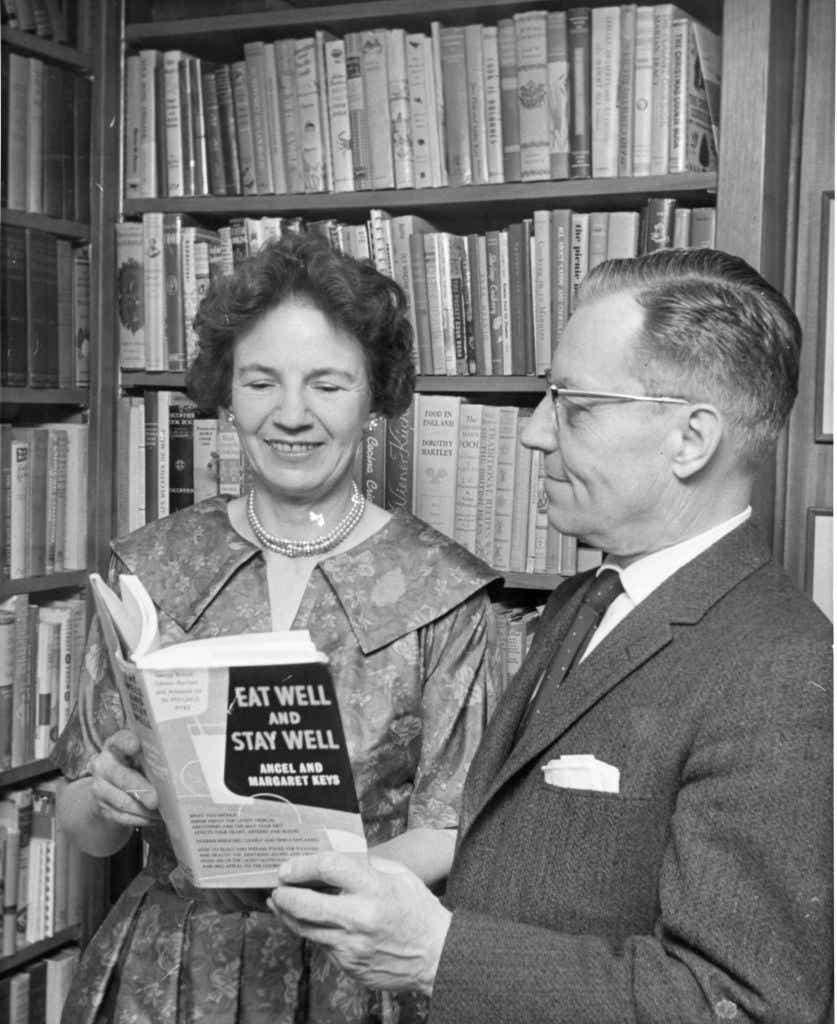

Earlier that same decade, a famous 1950 experiment had demonstrated the direct correlation between periods of starvation and periods of extreme overeating. As World War II drew to a close, Western governments were faced with a civilian population that had endured semi-starvation due to wartime conditions, so they wanted to know what semi-starvation’s psychological effects might be.

Ancel Keys directed what would become known as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment to answer this question by subjecting 36 conscientious objectors to a semi-starvation diet of half their normal intake. The starving subjects “ruminated obsessively about meals and foods” and “reported relentless hunger.” They experienced cognitive declines, gastrointestinal issues, and depression — symptoms doctors have pointed out are also associated with eating disorders. Some subjects even developed body dysmorphia, reporting anxiety about regaining weight during the experiment’s refeeding phase, despite reporting no negative feelings around their body size before the experiment.

During refeeding, when the men were allowed an “unrestricted” diet, they didn’t readopt their prior relationship to food, instead “succumb[ing] to eating binges” that caused “feelings of self-reproach” admitted in “hysterical, half-crazed confessions” and even followed by vomiting in some cases. The extreme hunger developed during semi-starvation lasted much longer than researchers had expected; it did not abate even after large meals. One subject was hospitalized after a severe binge. Subjects were still bingeing regularly and reporting extreme hunger five months after the starvation phase ended. Some admitted to scrounging in garbage cans for food.

The midcentury medical establishment did not see a connection between the semi-starvation in the experiment and the self-induced semi-starvation afflicting, say, a dieting woman, or the doctor-prescribed semi-starvation occurring in weight loss clinics. Perhaps it seems specious to compare an experiment explicitly focused on starvation to the experience of the average dieter or person in weight loss treatment, but in reality the conditions of Keys’s experiment were alarmingly similar to the diet regimens patients were inducted into by weight loss doctors back then, and are extraordinarily, alarmingly similar to diet plans prescribed to fat people today and those suggested in mainstream publications for people of any size. Keys’s subjects ate approximately 1,600 to 1,800 calories a day during the “starvation” phase, which is actually hundreds of calories higher than the daily total weight loss clinics commonly prescribed.

Those numbers are also hundreds of calories higher than the daily intake often suggested by popular programs like Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig, and MyFitnessPal today — for both people deemed overweight and those considered “normal.” A popular spa in California offers multiple daily calorie plan options, the largest of which reportedly clocks in at around Keys’s rations. As Naomi Wolf noted in The Beauty Myth, prisoners at the concentration camp Treblinka were given the same total daily calories prescribed at top American weight loss clinics when she was writing, which was also a higher total than the daily allotment during multiple stages of the ProLon Cleanse, a diet system sold by Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop. A 2020 study concluded that disordered eaters and chronic dieters (a Venn diagram I’d argue looks more like a circle) experience “psychological deprivation akin to those who starve.”

Yet binge-eating disorder (BED) is still too often considered a willpower issue associated with fat people, who are often directed to programs like Weight Watchers by doctors. One woman recalled visiting her physician multiple times seeking treatment for BED. Instead of a referral to a mental health provider, she was made to feel “like I was lazy, that I had no willpower, that I just needed to lose weight.” Telling this story to Refinery29, she said, “I left doctors’ offices in tears, with discounted Weight Watchers memberships.”

Despite the vast evidence base proving that diets don’t work, often cause eating disorders, and especially exacerbate binge eating, many doctors still disbelieve the psychological and physical underpinnings of bingeing. By and large, fat people with BED are still prescribed weight loss before they are prescribed eating disorder treatment. As the fat activist Deb Burgard has said, “We prescribe for fat people what we diagnose as eating disordered in thin people.” And what we prescribe is perversely likely to make them larger— as we’ve seen, dieting is correlated with long-term weight gain — and endanger their lives in ways then blamed on their size. All of this entraps larger people in a never-ending cycle of shame, blame, and pain in service of flawed diagnostic regimes and a profitable, fatphobic beauty standard.

Dead Weight is available in bookstores now. Excerpt courtesy of Clein/Penguin Random House