Here’s the thing about body image ideals: They’re ever-changing. That means, no matter how close you think you can get to attaining the “perfect” body or how many promises and products companies make to help get you there, you’ll always wind up feeling defeated.

This frustrating cycle is a consequence of living in an image-obsessed culture that sets us up to fail. If we keep striving for an “ideal” that’s forever in flux, diet and appearance-centered industries (the global market for weight loss products is valued at $255 billion) continue to profit.

While the media plays an undeniable role in the development of negative body image, it’s important to acknowledge that movies, magazines, and TV shows don’t cause eating disorders. These diseases are complex, multilayered illnesses that affect thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. That said, what we see onscreen, in print, and on social media absolutely can and does impact our self-esteem.

Ally Duvall, body image program manager at Equip, the online eating disorder recovery platform, believes the impact of media messaging is too profound to ignore. “We can’t discuss body image without looking at where these ideals come from and why they keep changing,” Duvall says. “Society pushes us to put everything on the line — our values, goals, self-worth, relationships — to chase ideals that are so restrictive, unobtainable, and constantly changing — and for what? The promise of never-ending happiness?”

In her 2006 paper titled “Body Image, Media, and Eating Disorders" (which was updated in 2018 due to its popularity as one of Academic Psychiatry’s most downloaded articles), lead author Jennifer Derenne, MD and Equip's VP of Clinical Care Delivery and Head Psychiatrist, chronicles changing body ideals through the decades. Derenne argues that "throughout history, the standard of female beauty often has been unrealistic and difficult to attain. Those with money and higher socioeconomic status were far more likely to be able to conform to these standards. Women typically were willing to sacrifice comfort and even endure pain to achieve them."

It’s worth taking a closer look at just how drastically the “ideal” body has changed over time and how the goalposts for what’s considered a “perfect” figure have kept moving throughout the decades. Understanding the fallacy of “perfection” may help you make more informed choices around the images, ideas, and products bombarding you every day and even empower you to take a stand against toxic media messages in your own way.

The turn of the century: The Gibson Girl

Born from an illustration by Charles Gibson, The Gibson Girl wound up being a standard of beauty for women of the age. The artist’s creation was pale and corseted (think: small waist, big bust), perhaps marking the beginning of an aesthetic trend toward a thin ideal. While the Gibson Girl wasn’t a real person, Evelyn Nesbit (sometimes considered the world’s first supermodel) was a close match.

The 1920s: The Flapper

The Roaring ‘20s brought about the liberal flapper aesthetic: Corsets were gone and clothing was much more casual — representative of the freedom some women were (supposedly) gaining as they won the right to vote. The look featured boyish/androgynous short hair and looser (but more revealing) garments. Heavy makeup was in, but bigger busts were not (bras were made to flatten larger breasts). According to one study, the bust-to-waist ratios among women featured in Vogue and Ladies’ Home Journal declined by about 60 percent between 1901 and 1925. The first Miss America, Margaret Gorman, was crowned in 1921 and largely considered the new aesthetic ideal: Petite, lean, and far less curvaceous than the (corseted and padded) ideal that preceded her.

The 1930s: The “Sex Siren”

While Gorman may have represented 1920s “goals,” by the early 1930s, change was on the way. In 1931, Photoplay Magazine declared Mexican actress Dolores del Rio as having the “best figure in Hollywood” thanks to her “warmly curved” and “roundly turned” figure. In contrast to the androgynous ideal of the 1920s, curves dominated in the 30s, with actress Jean Harlow (nicknamed “The Blond Bombshell”) leading the way.

The 1940s: The Starlet

Wartime fashion styles became more military-inspired and the look of the moment was a tall, squarer silhouette that contrasted the softer look of the 1930s but also amplified that decade’s preference for curves. Katherine Hepburn was considered one of the era’s icons for her commanding, fiercely independent onscreen persona and strong, tall body type.

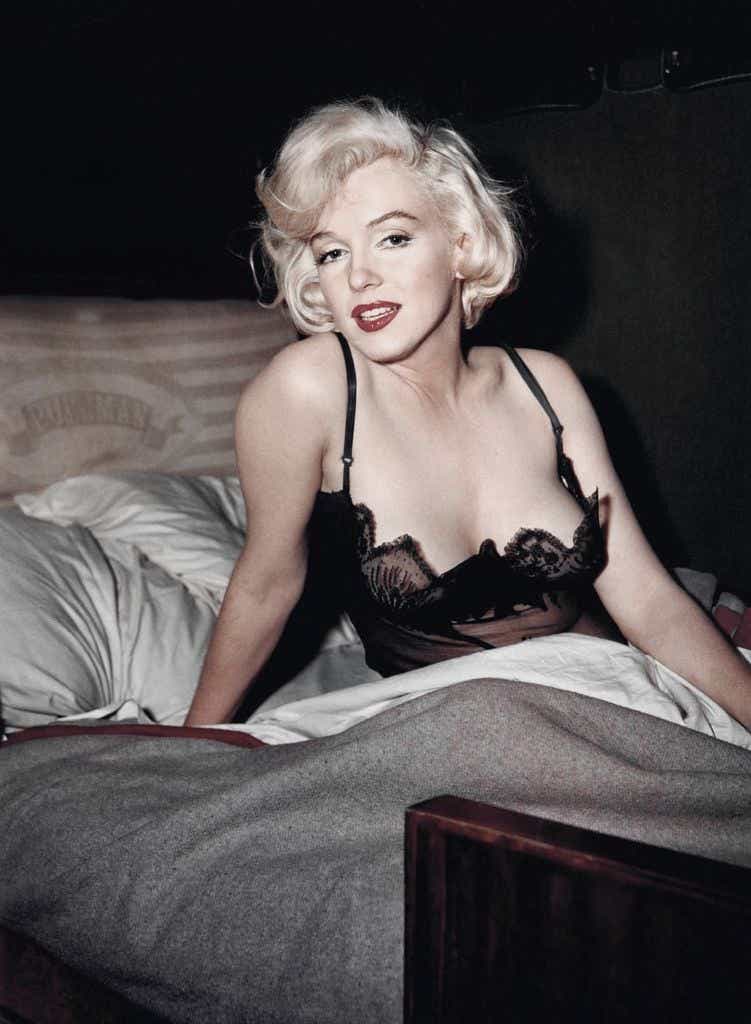

The 1950s: The Hourglass

The curvy aesthetic of the previous decades was magnified in the post-war ‘50s, with voluptuousness emphasized in fashion and the media. Ads of the era even advised “skinny” women to take weight-gain supplements to fill out their curves. Playboy Magazine and Barbie were both created in this decade, and while Marilyn Monroe is largely considered the representative ideal of the era, other stars like Elizabeth Taylor famously minimized their waists while accentuating their busts, a la Barbie. Monroe did (supposedly) however, take an early stand for body positivity, saying, “To all the girls that think you’re fat because you’re not a size zero, you’re the beautiful one, it's society who’s ugly.”

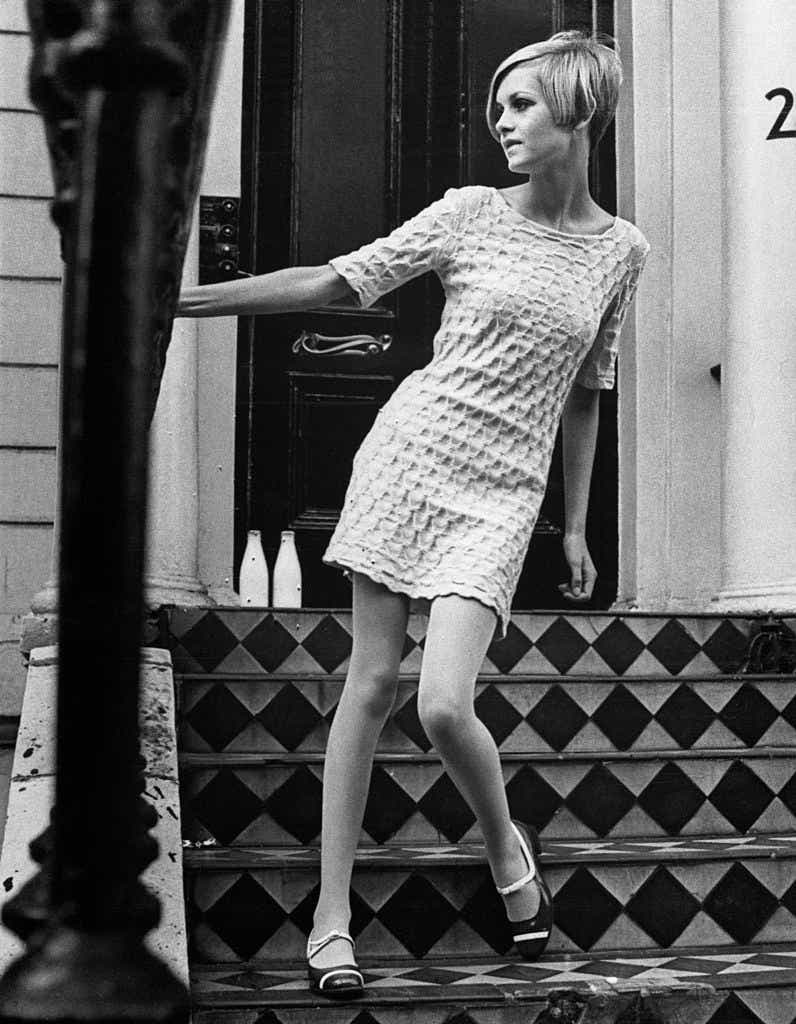

The 1960s: The Twiggy Aesthetic

In stark contrast to the 1950s, the ‘60s aesthetic was all about a slim figure, more reminiscent of the ideal of the 1920s. Supermodels like Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton popularized the mini skirt, which became a fashion staple and reinforced the quest for long, thin limbs to emulate the look.

The 1970s: The Thin and Busty Ideal

The thin ideal carried over into the 1970s, but the decade saw a bigger emphasis on larger busts with Farrah Fawcett at the media forefront, representing athleticism and femininity within the boundaries of a thin, petite frame. Anorexia first began to receive mainstream coverage in the 1970s, and singer Karen Carpenter dieted “at starvation levels over the decade — a practice that would claim her life in 1983.” Incidences of severe anorexia also rose significantly during the ‘60s and '70s.

The 1980s: The Super Fit Supermodel

The emphasis on athleticism intensified in the 1980s with aerobic exercise shows and videotapes becoming a widespread trend, compounding persistent diet pressures. The meteoric rise of supermodels like Cindy Crawford and Naomi Campbell also established a focus on longer, leaner bodies, and the athletic fashions and skintight fabrics of the era reinforced the obsession with “tight” and “toned” bodies. The August 1982 issue of Time argued that Jane Fonda and Victoria Principal were the new ideals of beauty because they were both slim and strong.

The 1990s: The Waif and Baywatch Ideals

While high fashion leaned heavily into the “heroin chic” waif look represented by Kate Moss (i.e. protruding bones and hollow cheekbones), the “Baywatch look” (thin with exaggeratedly large breasts) embodied by Pamela Anderson dominated mainstream media. Anorexia was associated with the highest rate of mortality among all mental disorders during this decade.

The 2000s: Strong and Sexy

Supermodels like Gisele Bündchen reintroduced the athletic aesthetic of the ‘80s, ending the “heroin chic” era of high fashion and ushering in an era of six-pack abs. The rise of stars like Britney Spears, who also popularized low-rise jeans and baby tees, reinforced the quest for flat abs and a “toned” appearance. Eating disorder related hospitalizations increased 18 percent from 1999–2000 to 2005–2006.

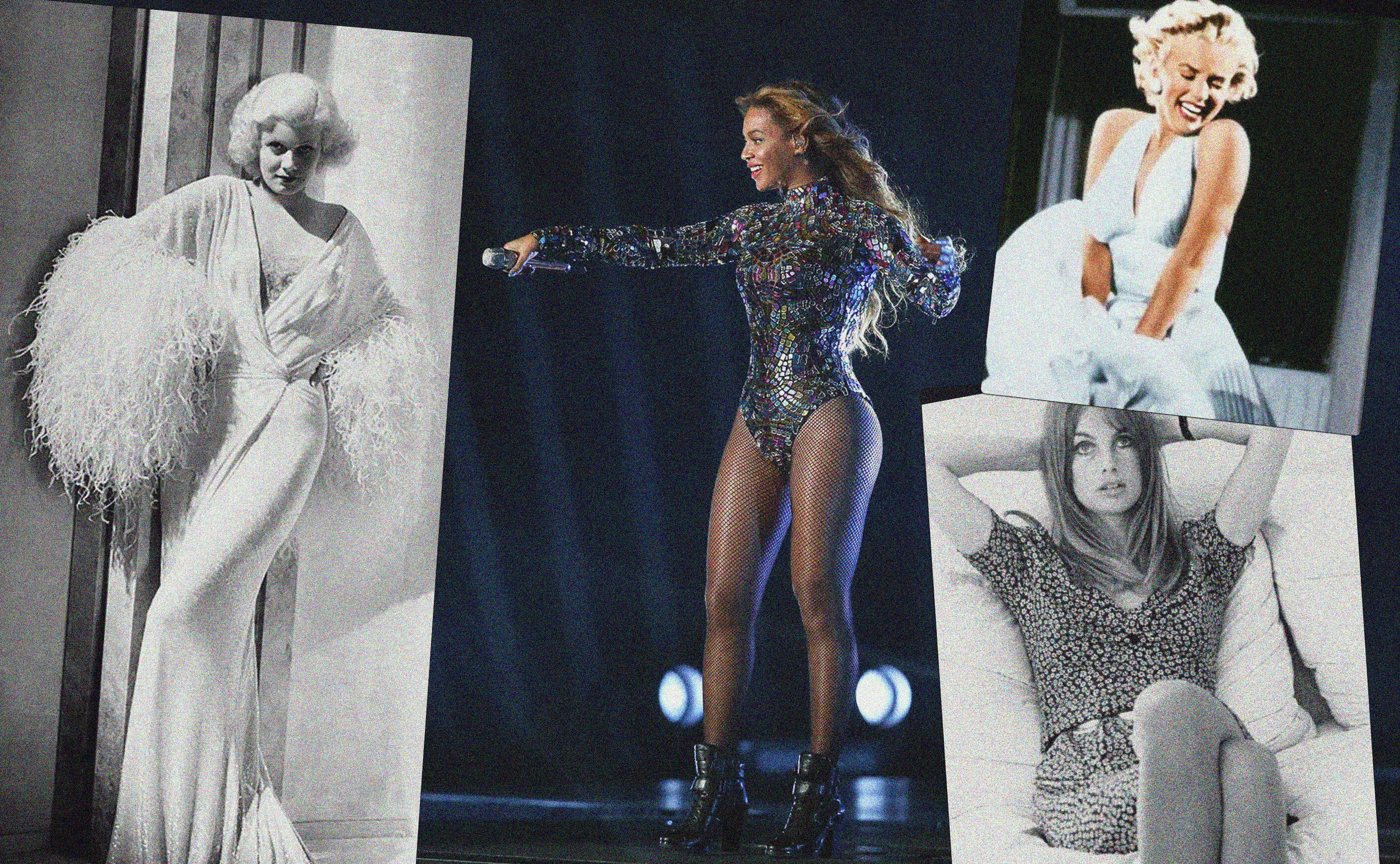

The 2010s: The “Bootylicious” Era

As stars like J.Lo, Beyoncé, and Nicki Minaj rose in popularity, the obsession with voluptuous backsides took off. The rise of the Kardashian family and the advent of image-based social media platforms like Instagram (launched in 2010) may have shifted the focus further away from historically white-dominant beauty standards (although many have accused the Kardashian/Jenner women of “blackfishing,” aka using tactics to appear Black). Some have also attributed the rise of specific plastic surgeries, like the Brazilian Butt Lift, to the popularity of the Kardashian aesthetic — between 2000 and 2018, such procedures increased by 256 percent. But the advent of social media also allowed greater visibility into an unprecedented diverse array of body types and the introduction of body positivity advocates like Megan Jayne Crabbe (formerly Body Posi Panda). She's amassed over a million Instagram followers, posting unfiltered and unapologetic photos that do not fit the arbitrary “ideal.”

What to take away

The biggest lesson from this crash course in body ideal history is that there is no actual ideal — these shifting “standards” are often created with the interests of industries in mind. There have, however, also been some steps toward progress. For example, before New York Fashion Week 2017, the Council of Fashion Designers of America sent out a memo to remind designers to seek out healthy models and a wider range of body types, saying the event is “a celebration of our city's diversity, which we hope to see on the runways.”

Celebrities like Lizzo, Lena Dunham, Serena Williams, Tyra Banks, and Demi Lovato have also become outspoken body positivity advocates and reclaimed the way celebrity bodies are discussed in popular culture. Lovato has said, “Don’t work out because you think you ‘need to.’ Do it because your body deserves love, respect, and healthy attention.” And Banks has stated, “Girls of all kinds can be beautiful...pledge that you will look in the mirror and find the unique beauty in you.”

While there’s no simple solution to the deluge of toxic messages we all receive daily, Duvall believes organizations like Equip can help educate and empower individuals to filter and respond to those messages. Through its Freeform body empowerment program launching publicly later this year, “Equip is working to help unveil the false promises and explore the deep roots of the appearance ideals, while also supporting folks in finding joy in their life regardless of how close they are to the ever-changing ideals,” she says. “We want everyone to start asking themselves, how would your life change if you could find happiness right now, without having to adhere to any ideals?”