Among the nearly 2 million people diagnosed with cancer each year in the U.S., African Americans have the highest death rate and smallest survival odds of any racial or ethnic group. Black women are less likely to get breast cancer than white women, but are 41 percent more likely to die from the disease. Colorectal cancer mortality rates are now 44 percent higher in Black men and 31 percent higher in Black women than in white men and women.

Along with these disparities, Black doctors and research scientists are still woefully underrepresented in the fight against cancer: About 14 percent of the U.S. population is Black, yet just 5.5 percent of physicians and PhDs in science, technology, engineering and mathematics are the same race. That’s why it’s so important to highlight Black doctors, researchers and advocates who are both working to reverse the deep inequities in cancer detection, treatment, and outcomes — and also seeking new treatments and advancing cutting-edge screening tools. “There’s a sense of responsibility and purpose when it’s your community that is being so disproportionately impacted by these health outcomes,” says John Carpten, an internationally renowned researcher involved in the “Cancer Moonshot” and one of five incredible leaders making a difference through their work to detect and stop cancer. This month, we’re highlighting five Black trailblazers who are leading the effort to narrow the gap in healthcare inequity.

John Carpten, PhD, chair of President Biden’s National Cancer Advisory Board

Carpten serves on the “Cancer Moonshot” — a federally funded effort launched by President Biden to cut the cancer death rate in half over the next 25 years. As the founding director of the Institute of Translational Genomics at the Keck School of Medicine at USC, Carpten is also a leader in developing individually-tailored medical treatment and drugs for cancer patients. He is a pioneer in investigating the biology behind disparities in cancer outcomes among populations, and emphasizes that treatment can’t be precise if the pool of patients used to design them is made up of only white people. “We have without a doubt been doing better with treating cancer as a whole, but we still see significant differences in certain types of cancer, and still struggle with closing the gaps in these disparities,” Carpten told NBC News.

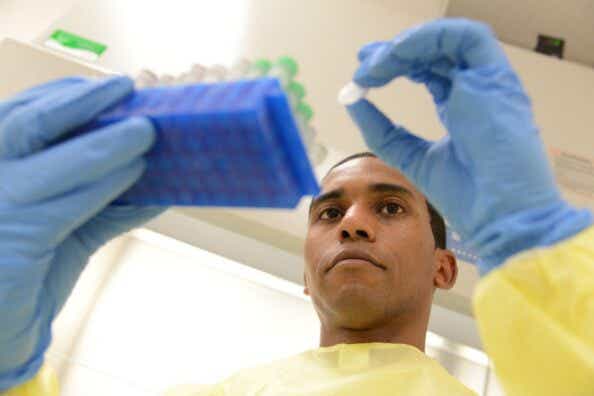

Dr. Isaac Kinde, VP of Technology Assessment at Exact Sciences

Kinde started his research career studying HIV as a college student, where he spent upwards of 40 hours a week in the lab. He was still a MD-PhD Candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine when he captured national attention a decade ago for his cancer research when he was named to Forbes’ 30 under 30 list of rising stars in science and healthcare “impatient to change the world.” Kinde is a co-founder of Thrive Earlier Detection which was acquired by Exact Sciences a year ago. Today, Kinde and his colleagues at Exact Sciences are working to change the outlook of a cancer diagnosis with a multi-cancer early detection test, using blood to detect multiple types of cancer earlier, when they are more treatable. Cancer is “a big problem,” Kinde told Johns Hopkins Magazine in 2020. “It’s an important problem. And it's a problem that I think I can help solve.”

Tamika Felder, cancer survivor, women’s health advocate, and chief visionary at Cervivor

Felder, named a “Cancer Rebel” by Newsweek in 2017, was 25 years old when a cervical cancer diagnosis altered the course of her life. She endured surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation before undergoing a radical hysterectomy to remove her uterus and her cervix. As a result, she lost her fertility.The experience inspired Felder to found Cervivor, a global community of patient advocates, and to counsel cancer survivors struggling to regain their sexuality and intimacy post-treatment. “When I was going through my cancer diagnosis, there weren't people that looked like me who were telling their stories,” Felder said in a recent interview with NPR. “I wanted to be there for people so they could see me and know that they are not alone.”

Linda Goler Blount, president and CEO of the Black Women’s Health Imperative

Blount leads the Black Women’s Health Imperative, the oldest national organization created by Black women to help protect and advance the health and wellness of Black women and girls. The group recently launched a campaign with Grammy winner Ciara, called Cerving Confidence, to encourage Black women to prioritize their health and commit to regular screenings to protect themselves against cervical cancer. Blount was also the first national vice president of health disparities at the American Cancer Society, where she focused on narrowing the health equity gap that creates barriers to thousands of Americans receiving life-saving cancer prevention and treatment services. “The difference we see in both the severity of disease and mortality really has to do with access: access to screening and access to quality treatment,” Blount told USA Today.

Dr. Hadiyah-Nicole Green, interdisciplinary cancer researcher, founder of the Ora Lee Smith Cancer Research Foundation

Green, an assistant professor at Morehouse School of Medicine, lost the beloved aunt who raised her, Ora Lee Smith, to cancer. Smith had refused treatment because she feared the side effects. This tragedy inspired Green to use her PhD in physics to develop a cancer treatment using laser-activated nanoparticles to target, image, and treat malignant tumors without side effects. Named one of USA Today’s “Women of the Century” and Business Insider's “30 Leaders Under 40 Transforming Healthcare,” Green started the foundation named for her aunt to fund clinical trials and translate these potential treatments from the laboratory to the doctor’s office in order to make cancer treatment accessible, affordable, and effective. “My goal is to change the way cancer is treated,” Green says.