After the birth of his daughter, Dr. Peter Attia, who hosts one of my favorite health podcasts, The Peter Attia Drive, began examining how he could live a longer life. In the process, he discovered that centenarians tend to smoke more, eat worse, and exercise less than the rest of us. How’s that possible? It’s apparently all in the genes. But even if you don’t have the right stuff, says Attia, “We can look at what those genes code for, and try to mirror the benefits.” Here’s his thoughts on how to live longer, and live better while you’re doing it.

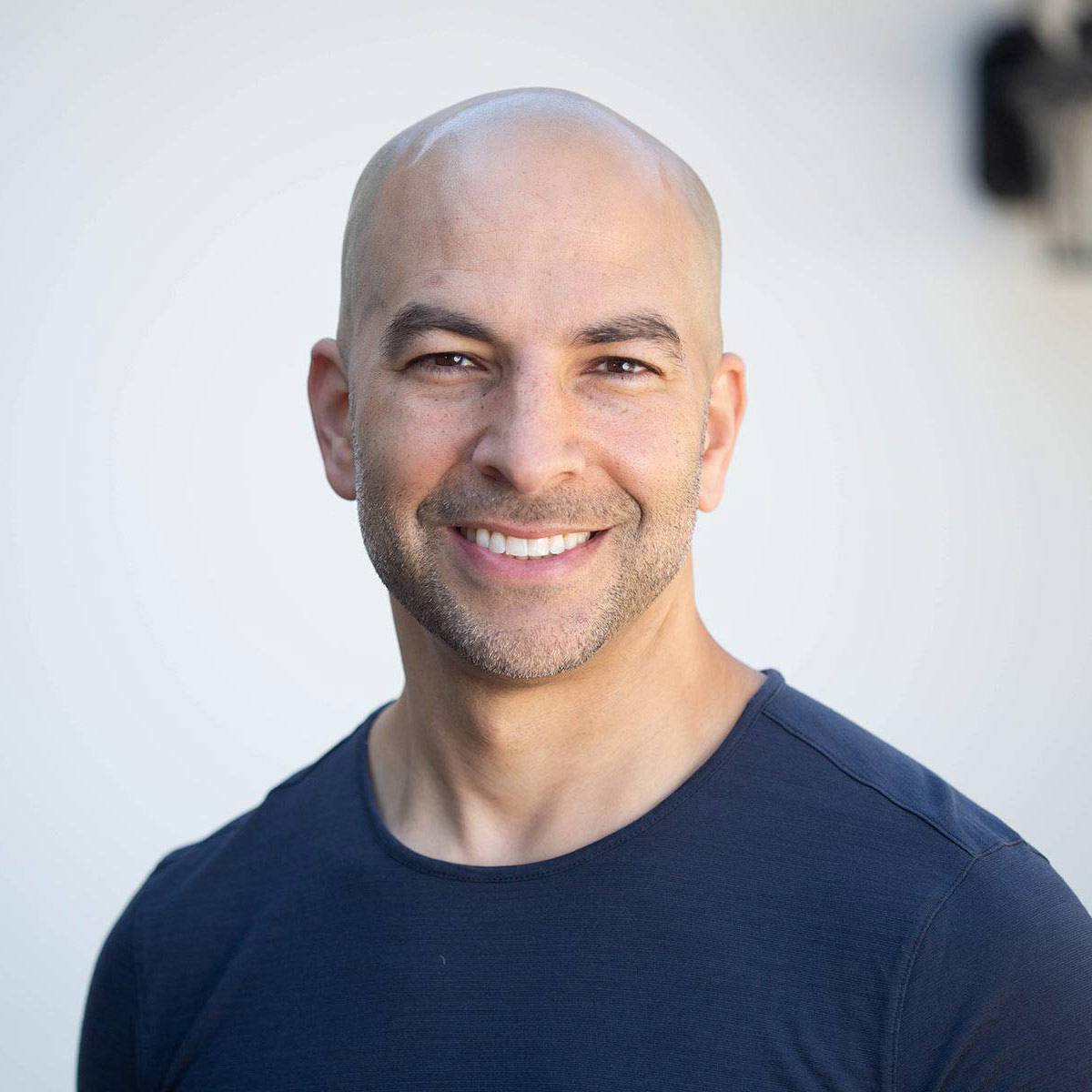

Katie Couric: You started out as a cancer surgeon and researcher. How did you become a specialist in longevity?

Dr. Peter Attia: I did start my medical training in surgery, specifically surgery pertaining to cancer. In fact, when I went to medical school, I’d planned to become a pediatric oncologist. However, before completing my training, I became pretty disillusioned with medicine in general, in particular the complete lack of prevention that went into the way we practiced it. It seemed that we could do so much in terms of last-minute efforts, but it was often too late and too often didn’t seem to impact how much longer or better a person could live. When I left medicine, I actually left it for good, I thought, and went as far as possible from it. I went into consulting, where I worked primarily in risk-management within the financial services industry. It was only after the birth of my daughter when I began to examine my own health that I become obsessed with the idea of trying to figure out how to delay the onset of disease — so could live as long as possible, to spend as much time with her as possible. Through that experience, I became more and more obsessed with the science of longevity and sought out the greatest research and teachers in this space.

You’ve done lots of research on centenarians: Are they doing something different than the rest of us?

In doing the research for my book, I looked as much as possible into everything that could be gleaned from the study of centenarians. They certainly seem like a very important population to study, given that they’ve already achieved what many of us would like to achieve — to live to the age of 100 or more. Much to my surprise, centenarians on average don’t do anything better than the rest of us. In fact, according to one of the most notable cohorts studied by longevity researcher Nir Barzilai, on average, they tend to eat worse, smoke more, and exercise less than average people.

Digging into this further, it becomes clear that the advantage centenarians have is clearly a genetic one. As one researcher jokes, the most important thing you can do to increase your odds of living to 100 is to pick the right parents. However, a deeper look at this idea reveals something quite interesting, which is that there are a cluster of genetic differences that offer centenarians the advantage of longevity. While those of us who don’t have those genes, which most of us, won’t have the luxury of inheriting that protection, we can look at what those genes code for and try to mirror the benefits of those genes.

A common genetic variant found in centenarians is a mutation for a gene called APOC3. In these people, APOC3 tends to be hypoactive, which gives them great protection from cardiovascular disease. Now, a person who’s very insulin-sensitive will also have very low APOC3, and this gives us some confidence that by working a little harder on our behaviors, we can mimic some of the phenotypes of these genetic gifts.

Can we really overcome our genes when it comes to lifespan? How much can we actually influence our longevity with habits and behaviors?

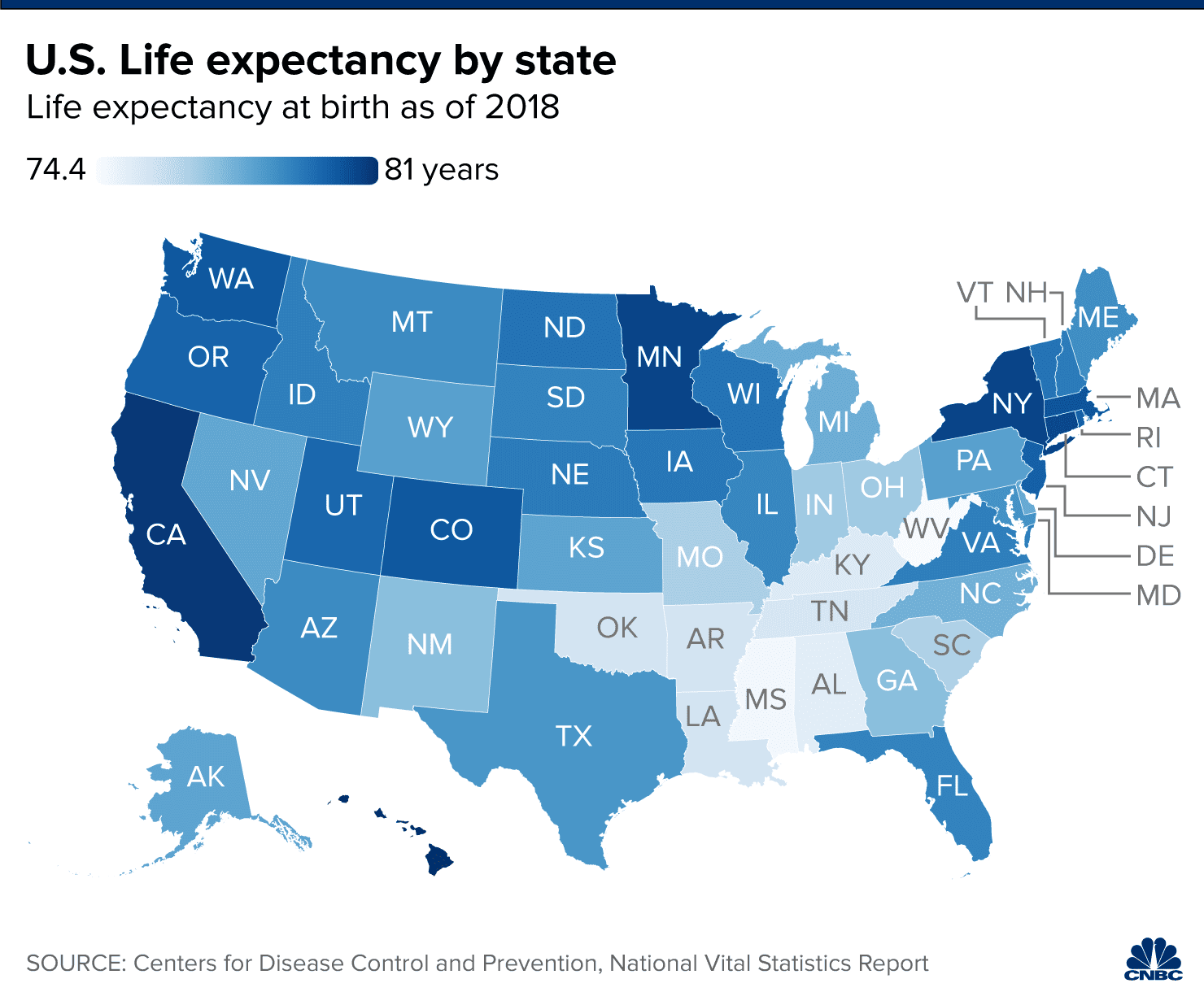

Genes do tell the majority of the story — but only when you look at extreme longevity, like people living into their 10th decade and beyond. But for people who live to an average lifespan, which is now approximately 80 in the United States, genes tend to play a very small role. That’s not to say the genes don’t matter, and certain conditions definitely do travel in families, like heart disease, cancer, or Alzheimer’s disease. But the genes that contribute to these conditions are virtually never single genes. There are genes that increase our susceptibility to these issues, and when you examine the literature, it’s clear that a healthy lifestyle can offer tremendous longevity, even to those of us who have “average” genes.

What’s a habit or behavior that people think is healthy, but is actually misguided?

That often seems to happen regarding exercise. I usually ask someone why they exercise, and I’m often surprised how unspecific the answer is. Usually, people say things like, “It makes me look good,” or “It makes me feel good,” or “It gives me more flexibility with what I can eat.” That’s all reasonable, but I think there’s a lack of focus on what’s a much more important concept: How is your exercise linked to increasing your lifespan? And how does exercise improve your healthspan? In other words, how is your exercise preparing you to age in the most functional manner possible? Too often, I see people exercising in a way that might provide some short-term benefits, but is increasing their risk of injury as they age. They’re doing things that they don’t have the stability, or ability, to do correctly — and that will come back to haunt them later in life.

Another example of this is people who spend far too much time focusing on very intense, long-duration, cardiovascular fitness. Relative to doing nothing, that activity is beneficial, but relative to more moderate levels of activity, it’s actually producing a diminishing return, and potentially causing harm — or increasing the risk of cardiac dysrhythmia later in life.

What are the downsides to an increased lifespan?

I think the most obvious example is if there’s any mismatch with healthspan. Lifespan, of course, means how long you live— your lifespan ends when you die, and its a very binary moment. But healthspan refers to the cognitive capacity for life, the physical capacity for life, and the emotional capacity for life. What patients have said to me is, “I don’t want to extend my lifespan if it doesn’t come with an increase in my healthspan.” In Greek mythology, it’s similar to the example of Tithonus, who was granted immortality but not eternal youth. So many aspects of medicine today focus more on delaying death than they do on increasing healthspan. Also, if an individual is increasing her lifespan beyond her friends and peers, she loses her loved ones over time.

Does studying longevity affect the way you live your own life? Do you think you’re more aware of the time you have left, and how to spend it?

Yes, I absolutely feel that way. I think much of this came from spending so much time around cancer patients and being with them when they died. Cancer, unlike heart disease or Alzheimer’s disease, doesn’t discriminate as much by age. Seeing young and patients die gave me a privileged perspective on the fragility of life.

The same is true from taking care of patients in a trauma setting, which I did a lot in my training. A number of times,I saw somebody die in a car accident. Obviously that morning when they left their home, they had no idea that this would be their last day. That gave me a great sense of how much is out of your control and how life is really quite short in the grand scheme of things. I haven’t figured out a way to completely master how I think about this, or come to terms with my own mortality. But I know that every day I can take actions to extend my life is worth whatever I need to do today to reap that benefit tomorrow.