There's a long tradition of misogyny in medicine, which was allowed to thrive, in large part, because women were barred from the field for most of its history.

That’s hardly the case today; women now account for nearly 40 percent of doctors in the U.S., according to research from the Association of American Medical Colleges. Yet here’s the ugly truth: Although the medical establishment is certainly more enlightened than it once was, the legacy of this bias continues to harm countless women, Elizabeth Comen, MD, a medical historian and oncologist, argues in her new book.

We may have moved past the more offensive and outlandish myths about the female body (i.e., that menstrual blood is toxic or that our smaller skulls are proof of our inferior intellect), but others endure. All in Her Head is a rigorous, deeply researched account of these falsehoods and how they've come to inform modern medicine despite our best efforts to eradicate them. It’s also a wake-up call, urging the discipline to recognize “that women’s health is not just about our uteruses or our breasts, but that we are fundamentally different from men and deserve unique attention,” Dr. Comen tells us.

Katie Couric Media: What are some of the women’s health myths that persist today?

Dr. Comen: In the field of oncology, for example, doctors are at least two times more likely to ask men about the sexual side effects of cancer-directed therapy than women. Part of that is how we’ve historically viewed women’s sexual desire as something that needed to be controlled or determined by their husbands or fathers.

Another example is heart disease. Heart disease is the number one killer of women to this day, but when I was in medical school, we were told that it was atypical for women to have it. Well, if we’re greater than 50 percent of the population and we’re dying predominantly from this disease, that shouldn’t be labeled "atypical." But there’s so much history that’s built that myth up.

I mean, one of the founding fathers of modern medicine, Sir William Osler, essentially said that chest pain in women was due to hysteria or neuroticism and believed that women couldn’t die from it. Well, we’re dying in droves, and in many cases, heart attack symptoms are being missed in women.

You write about the long history of hysteria in medicine. Can you discuss how it’s been used to write off serious conditions in women?

That’s why the title of my book is All in Her Head. I wish that didn’t resonate with so many, but wherever I go, I hear stories from women who've been dismissed by their doctors and told that it’s all in their heads.

Hysteria was a strictly female diagnosis that didn’t leave the medical lexicon until the 1980s. But it dates back to the Ancient Greeks; it’s derived from the Greek word for womb. The concept was that a womb wandering around the body was making women crazy. We no longer believe that, but we’re still living with the specter of the hysterical woman.

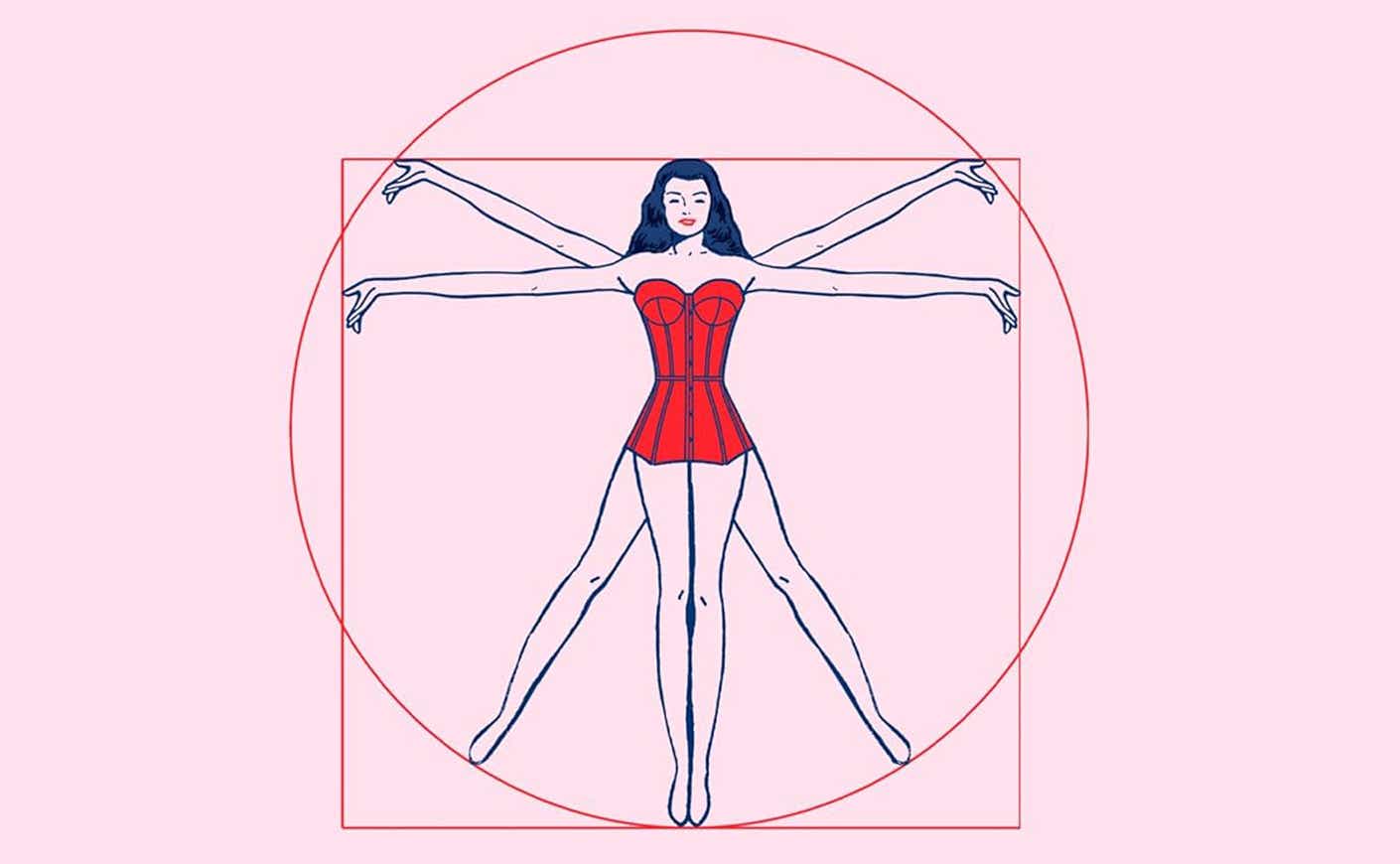

Another thing you discuss in your book is how, throughout history, women’s bodies have been viewed as an inferior version of the male ideal. Can you explain how that’s reflected in research?

Historically, women’s bodies were drawn as imperfect, lesser versions of the male. The assumption was that a drug that had been studied in men could be dosed the same way in women. It wasn’t until 1993 that women were even required to be included in federally-funded clinical trials, which means that some of the most important landmark studies for heart disease drugs, aspirin, or cholesterol drugs were predominantly done on men. Even the preclinical trials, which are conducted on animals, were mostly done on male mice.

Often when people think about the anatomical differences between men and women, they think about sex organs. But you write that the differences go far beyond that.

When I took anatomy classes in medical school, we’d learn about the heart, the GI, and the skeletal system in the male form. The only time we’d really look at the female form was to describe our breasts or reproductive system. But when you actually study the female body, it is significantly different from the male body in a whole host of ways — whether it’s the angle of our hips to our knees and how that relates to the prevalence of ACL injuries in women or how our GI tracts navigate our thoracic cavities to accommodate our reproductive organs. Medicine really has to catch up when it comes to studying, imaging, and diagnosing women.

Do you think the medical community at large has begun to understand how deeply embedded these are? And do you think enough is being done to address it?

I have a lot of optimism. I know there are many scary stories in this book, but plenty of amazing physicians recognize that we’ve all drunk the Kool-Aid and are taking the lead to remedy this. I think a tidal wave is coming: The White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research was just announced, which is going to funnel a substantial amount of money toward studying diseases in women. I think there are lots of reasons to have hope.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.