November is Pancreatic Cancer Awareness Month, which gives me an important reason to talk about my mother, Emily Couric, who died at 54 of pancreatic cancer, 15 months after her diagnosis. She had been healthy and vibrant for all of her life, and she was set to become lieutenant governor of Virginia after being re-elected to the state Senate. Many feel that she was destined to become Virginia’s first woman governor, but we will never know.

More than 64,000 Americans are diagnosed with pancreatic exocrine cancer each year (the more common and deadly kind, to be distinguished from less common neuroendocrine tumors). Like many who develop pancreatic cancer, my mom's diagnosis came in an advanced stage, when it had spread to her liver. Also like many, she had none of the common risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, or diabetes. Although symptoms of pancreatic cancer can include jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin), stomach and back pain, and weight loss, her case was a common scenario in which less severe symptoms —including abdominal bloating and irregular bowel habits — go undiagnosed for weeks or even months. These symptoms are often attributed to causes such as gastroenteritis or irritable bowel syndrome before a CAT scan is eventually ordered and cancer becomes apparent. That was the case with my mom.

Emily fought like hell for the remainder of her life, navigating difficult side effects from her chemotherapy regimens, a blood clot to her lungs that nearly killed her in the middle of treatment, and a clinical trial far from home while staying in a hotel. Despite all these best efforts, as I’ve now seen time and time again, nothing worked. She died, surrounded by all of us, on Oct. 18, 2001.

Her legacy includes the Emily Couric Clinical Cancer Center at the University of Virginia, where new treatments for pancreatic cancer are being discovered and tested in clinical trials. Oncologists like me work to help people with pancreatic cancer live longer and better lives, but only 12 percent of patients are alive five years after diagnosis, and the average survival is less than one year for those unable to undergo surgery because the cancer has already spread. As a result, many of us who work with people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer are focused on early detection of the disease, before there are symptoms, when tumors are small and haven’t yet spread, which gives surgery a much better chance of curing the patient. There is already evidence that the percentage of people diagnosed with early-stage, curable pancreatic cancer is increasing. The standard of care now includes early detection programs and screening individuals from families with familial pancreatic cancer, which is defined as two first-degree relatives diagnosed with pancreatic cancer — for example, two siblings or a parent and child.

But to save more lives, we need to do better. The Pancreatic Cancer Early Detection (PRECEDE) Consortium is an international, multi-institutional, collaborative group of experts working together to increase survival for pancreatic cancer patients by improving early detection, screening, and prevention, with the aim of substantially reducing the number of deaths around the world. People with a family history of pancreatic cancer who are seen at a PRECEDE site undergo genetic counseling and testing, and experts make individualized recommendations for using MRI and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) — typically done annually on an alternating basis — to screen for early, asymptomatic pancreatic cancers. These cancers can be removed by surgery before they spread to other organs and become incurable. Individuals without a family history of pancreatic cancer but with mutations in genes that increase risk (such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and ATM) should also discuss screening with their doctor.

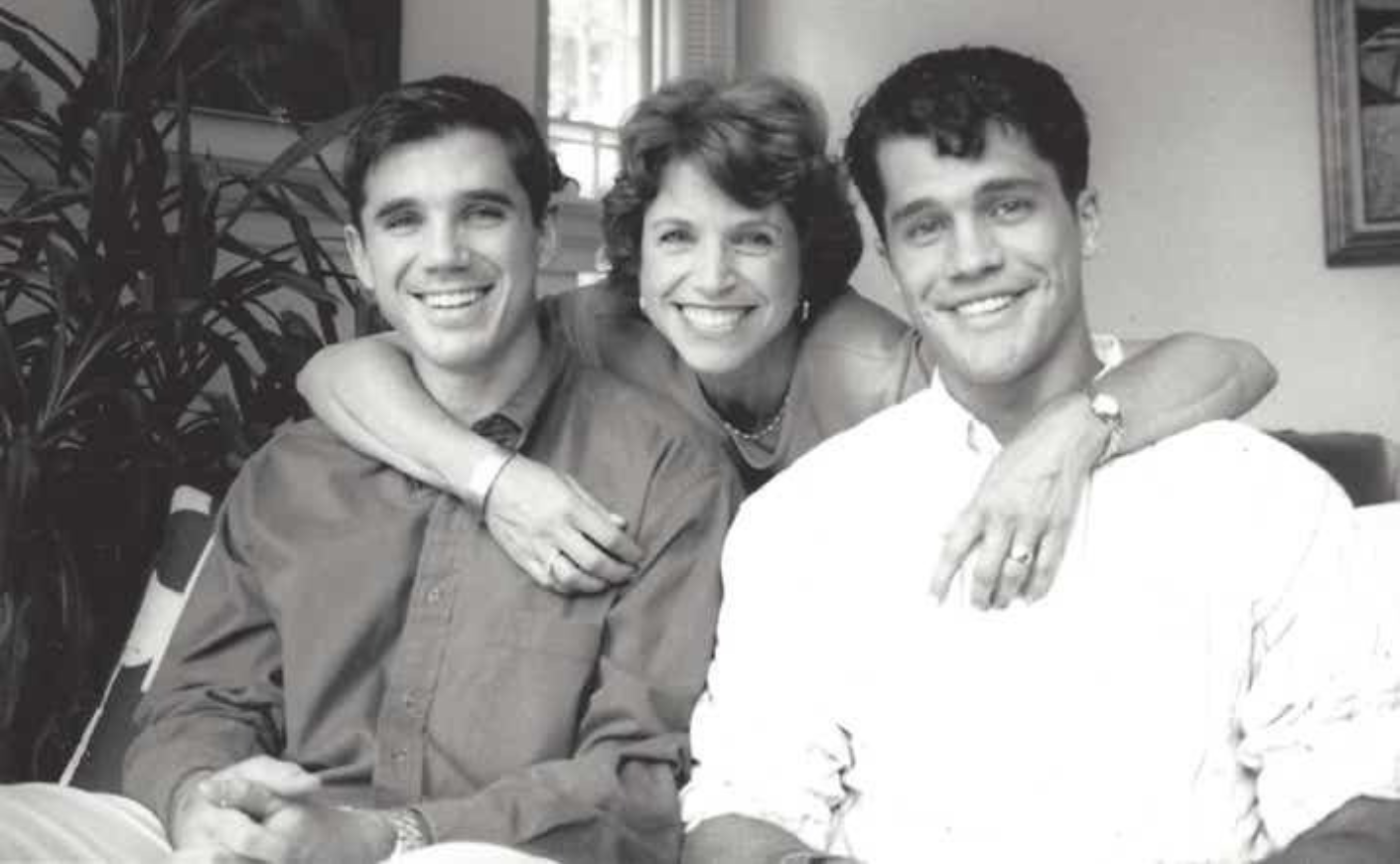

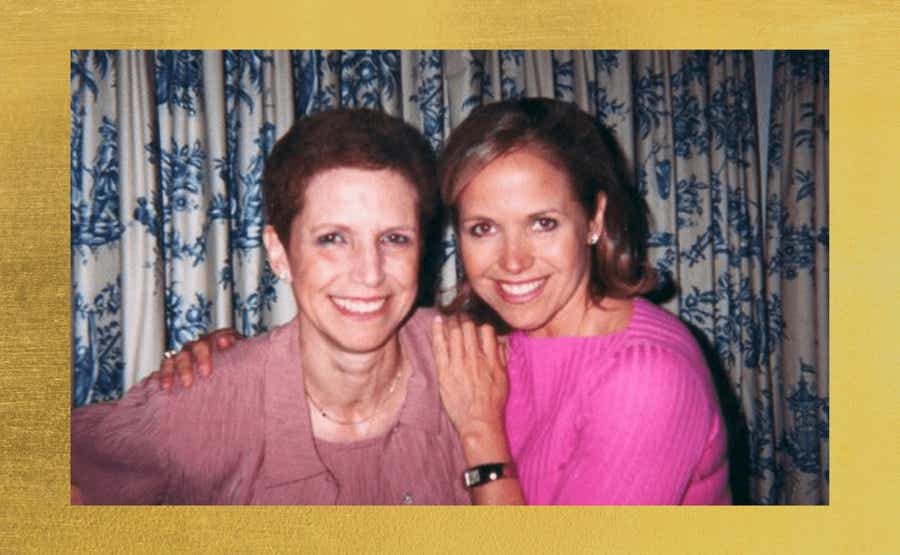

Like many cancers, pancreatic cancer is a particularly insidious one, because most people, like my mom, are diagnosed too late for a successful intervention. I miss her every day. But the best way for me to honor her is to be vigilant about my own health. That’s why my brother Jeff, my Aunt Katie, and I are part of the PRECEDE program. Since its inception, 16 cases of early-stage pancreatic cancers have been detected, and those people are living proof that screening saves lives. If you’d like more information for yourself or for anyone you know who has been impacted by this disease, you can do so right here.

Ray Wadlow is a gastrointestinal oncologist and the program director of the hematology-oncology fellowship at Inova Schar Cancer Institute — and the nephew of our very own Katie Couric.