When Vinnie Myers first started tattooing, he was in the military and just out to make a few extra bucks. He rigged up an old tape recorder motor with an E-string from a guitar, which he used to repeatedly pierce the skin of countless biceps, charging $20 a pop.

“We did $20 'name Saturdays' for anybody who wanted a name or a word tattooed on them,” Myers recalls. It was “very primitive” and by his own admission, probably not something most people would want these days.

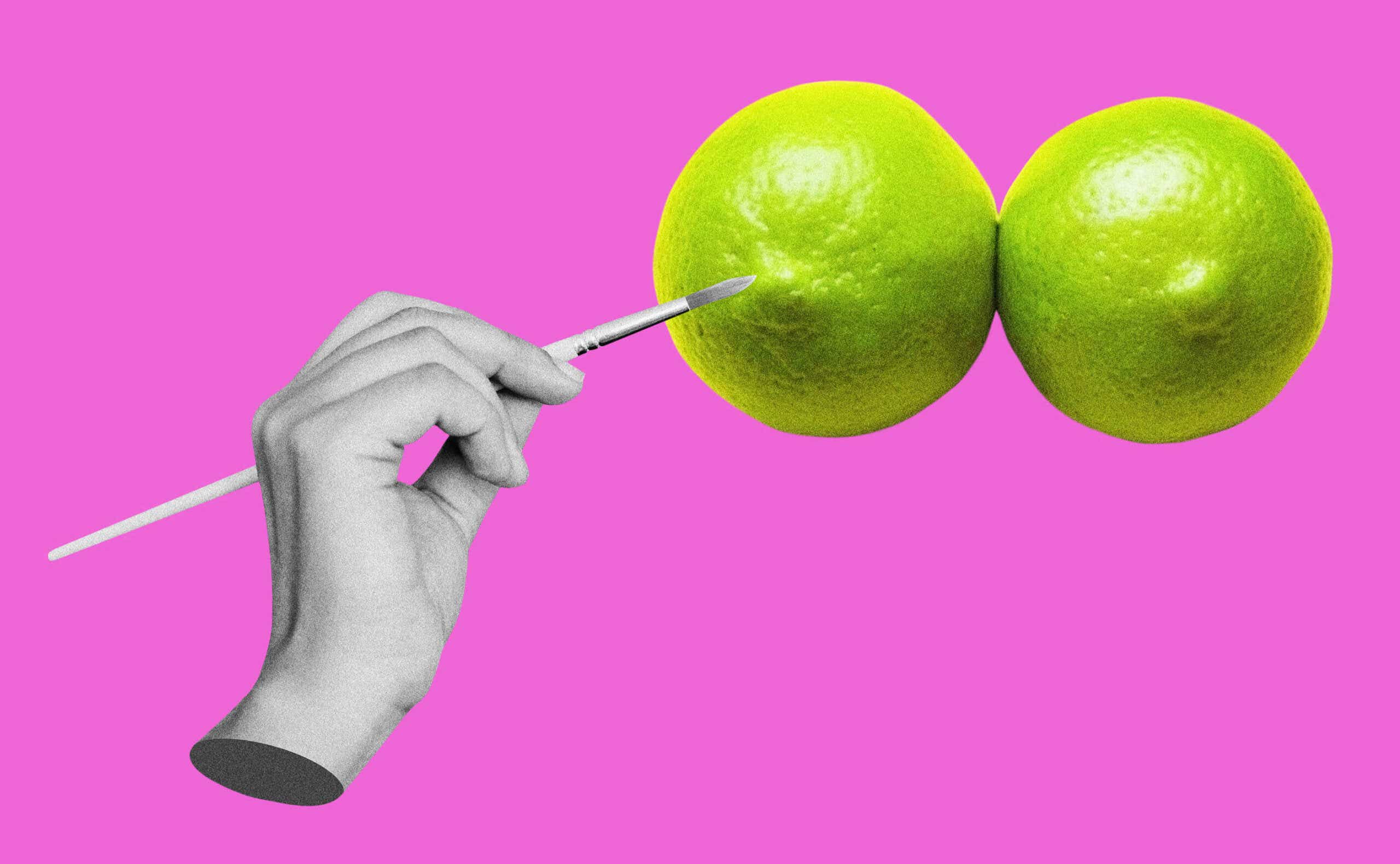

Fast-forward a few decades, and Myers is still working with ink — albeit with much more sophisticated implements — but his career has taken an unexpected turn. The 61-year-old has become the top artist working in tattoo nipple and areola reconstruction for breast cancer survivors. By his own estimation, he’s served between 13,000 to 14,000 people — meaning in his over 20 years in the business he’s replicated as many as 28,000 nipples.

Myers says he never dreamed that he’d end up here: The path just sort of appeared one day in 2000, when a woman visited his tattoo parlor in Carroll County, Maryland.

“She’d just had prophylactic mastectomies done, which was unheard of at the time because no one was doing genetic testing back then,” says Myers. “But she had a strong family history and decided she was going to do [the mastectomies] out of safety concerns.”

She wanted Myers to help with the finishing touches, so to speak, on her breasts — giving her photorealistic nipples via tattooing — and although he’d never done anything like it before, Myers was game. At the time, there weren’t really specialists working in the space: Physicians assistants and nurses inexpertly applied tattoos onto their patients' newly formed breasts, he says. But they weren’t trained artists, and didn’t have experience in creating dimension or thinking about proportions like he does. Myers figured that if he could reliably tattoo a portrait of Abraham Lincoln onto a bicep, “I could certainly tattoo a nipple on someone.”

Soon after, Myers met a woman working at the Johns Hopkins Breast Center and tattooed her, too. “After that, word sorta got out,” he says. Plastic surgeons began sending their patients to Carroll County and women started walking in — first from all over the country, then from all over the world. Business was booming, and in time, Myers needed a second pair of hands to keep up. That’s when his daughter Anna joined the family business.

“I didn’t even realize women needed nipple tattoos after they had breast cancer,” he says. “It’s evolved and become this really life-changing thing for me and a lot of other people.”

And even though he’s done literally thousands of nipple tattoos at this point, he still finds each case challenging. From a physical standpoint, it can be tough working on sometimes delicate or scarred tissue, and it can be an ordeal emotionally, both for him and the client.

There’s an intense amount of pressure that comes with trying to make someone feel whole again after surgery, says Myers. “It’s critically important, because they’ve been through this whole thing and the last thing you want to do is get the last step wrong. It’s stressful.” That's one of the reasons why, 13 years ago, Myers almost decided to give up.

“At one point, I came into work and I told the people there that I wasn’t gonna do this anymore, that I was done with it,” he says. Then 30 minutes later, Myers got a call from his sister, Lauren: She’d just been diagnosed with breast cancer. Myers took it as a sign.

“It’s like I tried to go against what I was supposed to be doing,” he says. (Lauren had a lumpectomy and is currently in remission.)

Now, Myers exclusively works in nipple reconstruction, tattooing them both in their entirety and touching up nipples that have been rebuilt surgically.

It’s deeply fulfilling work, he says. Myers has helped establish this field overall, which now has many experienced artists working within it, and helped countless people in their breast cancer journeys.

“I haven’t lived through cancer, and I’m never really going to understand what it means for the client,” says Myers. “But it’s a good feeling when they say they’re happy with my work.”