It’s easy to look back on the time before technology ruled our lives as “the good old days.” Kids played outside instead of burying their faces in their devices! Everyone trusted the news! Friends kept in touch by talking on the phone, rather than through Facebook posts and text messages! But when you dig a little bit deeper, it’s clear that innovations in technology have led to hugely positive and even lifesaving breakthroughs — particularly when it comes to breast cancer.

In the early 1900s, when the average lifespan for an American woman was just 48 years, women were likely too preoccupied with the dangers of now-preventable diseases like consumption or pneumonia to even worry about a potential breast cancer diagnosis. If you were an adult in the early 1970s, you may not have had to worry about the 24-hour news cycle, but you also probably didn’t have access to a mammogram.

This Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’ve highlighted some of the biggest historical breakthroughs in the breast cancer space starting all the way back in 400 BCE. To help us make sense of the more modern advances, we enlisted the help of Christy Russell, MD, former director of the USC/Norris Breast Cancer Center and current Vice President of Medical Affairs at Exact Sciences. Dr. Russell also shared her insight on what we might be able to expect for the future of breast cancer.

400 BC: Cancer is named

Hippocrates, known as “the father of medicine,” (ever heard of the Hippocratic oath? That’s all thanks to this guy) coined the term “cancer.” The word is possibly derived from the Greek word for crab, due to the invasive nature of the disease. We don’t know what sort of invasive crab problem they were having in Greece at the time, but it must have been pretty bad.

And after a quick 2100-year jump…

1786: John Hunter makes first diagnosis of a tumor

Scottish surgeon John Hunter, physician to King George III, suggested that tumors weren’t part of the body and could be removed, although anesthesia hadn’t been discovered yet. So to anyone who got a tumor removed at that time: we’re truly sorry.

1842: First survey on cancer deaths

Italian physician Domenico Antonio Rigoni-Stern did the first survey on cancer deaths and found that breast and uterine cancers were most common in women, together resulting in two thirds of cancer deaths. He also made erroneous claims that cancer was linked to sexual activity in women, so suffice it to say he was not our favorite guy on this list.

1894: First recorded radical mastectomy

American doctor William Stewart Halsted published the first paper at Johns Hopkins on his success performing a radical mastectomy. The original procedure was dangerous and imperfect, but it inspired hope that the disease could be treated and paved the way for other doctors to attempt the procedure in a safe and effective way.

1943: Chemotherapy is born

The two World Wars gave rise to the use of mustard gas. When physicians studied the impact of the gas on bodies of deceased soldiers, they found that their lymph nodes had disappeared. This led to the theory that these chemicals could be used to treat lymphoma (cancers of the lymph system), and thoracic surgeon Dr. Gustaf Lindskog successfully treated a patient with a large neck tumor. Chemotherapy wouldn’t become widely used until the late 1950s, when it was found to be effective in the treatment of childhood leukemia.

1976: American Cancer Society recommends the mammogram

Medical imaging had already been around for quite some time — in fact, X-rays were discovered in 1895 when Wilhelm Roentgen took the first X-ray image of his wife’s hand wearing a ring. For a long time, X-rays were used as a novelty attraction at places like state fairs…before we knew about the adverse impacts of radiation. Whoops.

Flash forward to 1965, when Charles Gross altered the technology to create the first machine specifically designed for mammography. It wasn’t until a decade later that it came into popular use in the US, with the American Cancer Society recommending an annual mammogram for women over 50.

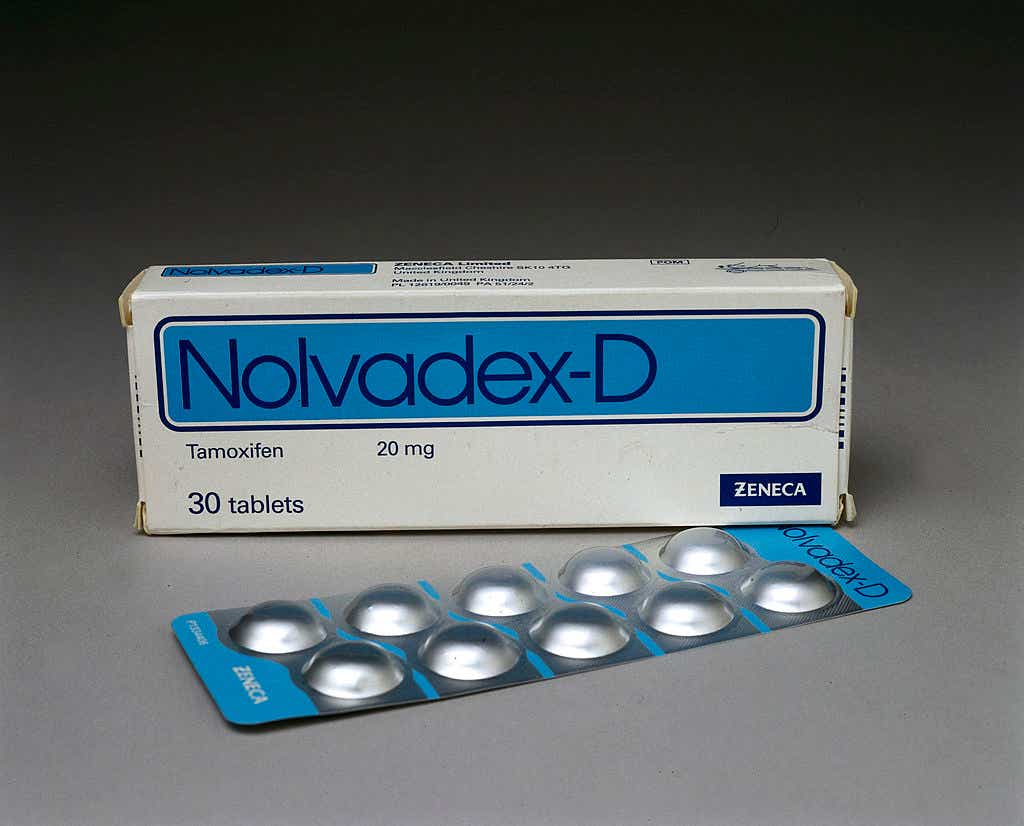

1978: Tamoxifen approved by the FDA

A huge breakthrough in cancer treatment was the approval of the drug tamoxifen. Dr. Russell explains: “A receptor is just a protein that sits through a cell wall and acts like a catcher’s mitt, and it’s specific for each hormone. So estrogen receptors are only going to interact with estrogen, unless you create a drug that makes the receptor think it's estrogen. That’s what tamoxifen does.” A whopping two in three breast cancers are hormone receptor positive (HR+), so they’ll respond to tamoxifen.

1982: Her2 gene discovered

Another very big deal in the treatment of breast cancer was the discovery of the Her2 gene. According to Dr. Russell, “We all have two copies of the Her2 gene in every cell in our body. But in up to 20 percent of breast cancer patients, instead of having two copies, you have an overproduction of these genes which then causes cancer to grow very rapidly.”

1995: BRCA gene is discovered

The discovery of the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 gave concrete evidence that breast cancer can be hereditary, solidifying the idea that women who had a direct family member with breast cancer should get screened early.

1998: Use of trastuzumab drug is approved

Remember the Her2 gene? Figuring out it existed was just step one. It took some more time to discover the Her2 receptor, then how to measure that receptor, and finally, a drug called trastuzumab. Says Dr. Russell: “It works as an antibody to basically shut down those replicating cells. There’s a huge benefit in women who are prescribed this therapy.” Thanks, science!

2004: Genomic testing enters the playing field

Here’s where we get into some really cool and almost futuristic ways of personalizing breast cancer treatment for each patient. In the past, essentially every woman with breast cancer got chemotherapy — often for 6-12 months following surgery — because physicians didn’t know who would and would not benefit from it. Enter the Oncotype DX Breast Recurrence Score Test. Dr. Russell explains: “For this test, we take a tiny bit of the tumor from the surgery and extract RNA from it. Eventually the patient gets a Recurrence Score result between zero and 100 — the higher the score, the more likely the cancer is going to metastasize, or spread. This was a major step in helping oncologists determine the correct course of treatment. If a score is low or intermediate, there’s a benefit from endocrine therapy, like tamoxifen. On the other hand, women with a low score have essentially no benefit from chemo, but women with a high score have a huge chemo benefit. This represents up to 70 percent of women with zero to three lymph nodes involved."

A low Recurrence Score result does not mean there is no chance that your breast cancer will return. And a high Recurrence Score result does not mean that your breast cancer will definitely return. So, your treatment decisions still depend on your unique situation and personal preferences.

So… what’s the future of breast cancer treatment?

Sadly, Dr. Russell doesn’t anticipate any sci-fi solutions like organ cloning or cancer-sniffing robots are anywhere on the horizon, but she thinks the most likely scenario is that doctors improve on the therapies we already have. She says: “For women who have triple negative breast cancer, all we had to offer is chemotherapy. Now we have learned that using therapy to harness the immune system by using a class of drugs called checkpoint inhibitors can substantially improve outcomes for women with triple negative breast cancer.”

“When it comes down to it, the future of breast cancer is figuring out which patients will benefit from new medications, and which patients are not benefitting from the medications they are currently getting,” says Dr. Russell. “Does everybody need radiation? Or can we figure out which cancers absolutely need those therapies, and use gene testing of the patient’s cancer to inform more precise therapy for that patient. A lot of that is in the works right now and could have huge future impacts on cancer outcomes.”

The information in this article is not clinical, diagnostic, or treatment advice for any particular patient. Providers should use their clinical judgment and experience when deciding how to diagnose or treat patients. Exact Sciences Corporation does not recommend or endorse any particular course of treatment or medical choice.