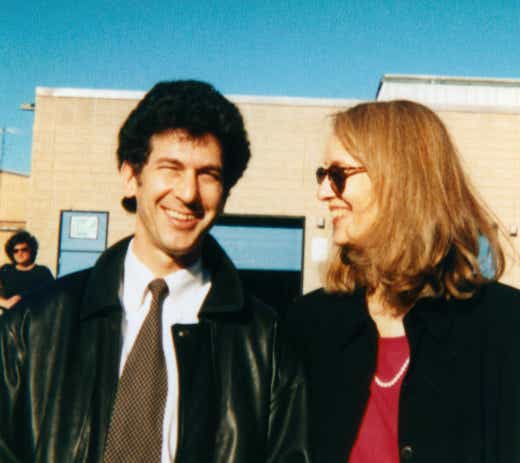

Dr. Barrett Rollins is an oncologist who was married to another brilliant world-renowned oncologist, Jane Weeks. But when Weeks was diagnosed with breast cancer, she hid it from him, and everyone else she loved. In this excerpt from his incredibly moving book In Sickness, Dr. Barrett Rollins looks back at why his wife kept this bleak secret — and why he then helped her keep it under wraps.

After three decades of living with Jane, I had become adept at adjusting to her quirky behaviors. None was more deeply embedded than her aversion to seeking medical care for herself. In all the years I knew her, she never had a primary care doctor and never went to a routine medical appointment. She had one root canal when her tooth pain became unbearable but, other than that, she never went to a dentist or a hygienist. She suffered for years from intense lower back pain and sciatica but never sought help. Despite working in, and eventually leading, a world-class academic center devoted to cancer screening and prevention, she never had a single mammogram, Pap smear, or colonoscopy.

Sometimes the consequences of her stubbornness could be alarming. About 15 years earlier, Jane started having recurring attacks of excruciating abdominal pain and fever. I worried that she might have diverticulitis or worse. But no matter what I said, I could not convince her to see a doctor. Instead, she called our drugstore to prescribe herself a powerful antibiotic and asked me to pick it up for her. Sometimes this strategy worked, and she would recover after a few days. Other times the first antibiotic didn’t do the trick and she would prescribe herself a second one. During one protracted episode, she missed several weeks of work while she lay in bed, waiting to see if she would get better. She eventually did, and life went on.

I don’t know where Jane’s intense medical phobias came from, but they had dire results. They were, in fact, the direct cause of the misery she was now experiencing.

One Saturday morning about four years before the pulmonary embolism, I heard Jane calling to me from behind the closed door of our bathroom. I opened it to find a horrific sight. Jane was lying on the tile floor. The caftan she wore on weekends was partially unzipped and over her right shoulder was a blood-soaked towel.

“My god!” I nearly shouted. “What’s wrong?”

“I’m dying,” she said calmly.

“What are you talking about?” I asked, skeptical but concerned about her uncharacteristically dramatic assertion.

“I have breast cancer,” she said.

“Really?” I said, still skeptical. “How do you know?”

Jane didn’t reply. She continued to lie on the floor, looking anywhere but my direction.

I let a minute pass.

“Seriously, hon,” I said in a softer tone. “What’s this about?”

Again, no reply.

“Look,” I said, “I can’t help you if you won’t tell me what’s happening.”

“Fine,” she said, with a note of disgust creeping into her voice. “I have breast cancer that’s spread to my skin. It’s invaded a blood vessel and now I’m bleeding to death.”

“Jesus Christ! Let me see how serious this is,” I said, reaching for the zipper.

“No!” she screamed. “Don’t touch me! I just don’t want to be alone when I die.”

“How do you know you’re dying?” I said. “How do you even know this is breast cancer?”

“Oh, I am and it is.”

“Well, I can’t just let you die here on the floor,” I said, reaching for my phone. “I’m calling 911.”

“No, no, no!” she screamed again. “Don’t you dare. I’ll never forgive you if you do.”

I froze. I was utterly loyal to Jane but this behavior was insane. We sat in silence for a few more minutes.

“Why don’t you read to me?” she finally said. She’d brought the New York Times into the bathroom. It was lying on the floor next to her, so I picked it up and started reading aloud.

After an hour, Jane still wasn’t dead.

“I think the bleeding stopped,” she said.

“Thank god,” I said. “Now, show me where the blood was coming from.”

“No, no need,” she said flatly. “I’m fine now. Go do whatever it is you were doing when I called you in here. Really, I’m fine. Go on.”

When Jane emerged from the bathroom an hour later, she still wouldn’t answer any of my questions. No matter how much I pleaded, she refused to be seen by a doctor and angrily told me never to ask her again. She went about her usual Saturday activities as if nothing had happened.

I was shaken. Did she really have cancer? How could she be sure unless she let a doctor look at it? She might be right…but she might be wrong. How could she possibly know how serious it was? When she told me that she was “dying,” did she say that because of the bleeding, or did she know more than she was letting on?

Everything about her medical condition was unclear. But what was abundantly clear was her desire not to discuss it. I had to decide: do I use whatever limited leverage I might have to keep confronting her, or do I comply with her wishes by denying that any of this ever happened?

I chose the latter. I spoke to no one.

Now, I had to confront the fact that yesterday, the day of her pulmonary embolus, and for many, many days before that, I had known about Jane’s breast cancer. I had never seen it and I had no idea how serious or widespread it was, but I could no longer tell myself that I’d been unaware of it.

Jane’s revelation on the bathroom floor made me realize that some of her inexplicable behaviors—many involving a ratcheting down of intimacy and communication, and a ratcheting up of compulsive tics—had arisen from the anxiety she must have felt after first discovering her cancer. Those changes had begun six years before the bathroom floor incident, which meant that, by the time of her pulmonary embolus, Jane had been hiding her cancer for a decade. And I had been deeply complicit in her secrecy for the last four years.

Why had I acquiesced? In part, it was just another example of giving Jane whatever space and support she needed to calm her anxieties. My habit of accommodating her eccentricities had become deeply ingrained.

But there was more. On that Saturday afternoon four years before her collapse, I had witnessed a medical emergency—the bleeding—and learned about my wife’s shocking cancer diagnosis. I’d had an overwhelming impulse to act but suppressed it because Jane commanded me to, and I felt powerless to oppose her. What was that about?

There was no better feeling in the world than being in Jane’s good graces. Her formidable intelligence and finely honed tastes combined to make her approval something special. A nod made you feel like a million bucks. And for exactly the same reasons, her disfavor was crushing. This was true for anyone who interacted with Jane but, of course, I felt it much more intensely because love was added to the mix.

I had crossed Jane once or twice in our marriage and her response had been to withdraw — not just her affection but everything. Being frozen out felt like the worst punishment imaginable. I would respond with a desperate scramble to find anything that might restore me to her favor, including, in this case, a promise not to do anything about her breast cancer.

Now I felt deeply ashamed of my inaction. Fear of Jane’s displeasure was an absurd excuse. I asked myself, what kind of husband could stand by idly for four years while his wife’s breast cancer grew? I’m still asking that question.

This excerpt from Dr. Barrett's memoir, In Sickness, was reprinted with permission from Post Hill Press / Simon & Schuster. Watch the book trailer right here: